The very first major league All-Star Game took place 90 years ago on July 6, 1933. Conceived as part of Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair, it was played before 47,595 fans at nearby Comiskey Park.

The game was a big hit, so Major League Baseball repeated it the following summer at the Polo Grounds, then every subsequent year except two: 1945, which was canceled due to World War II travel restrictions, and 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

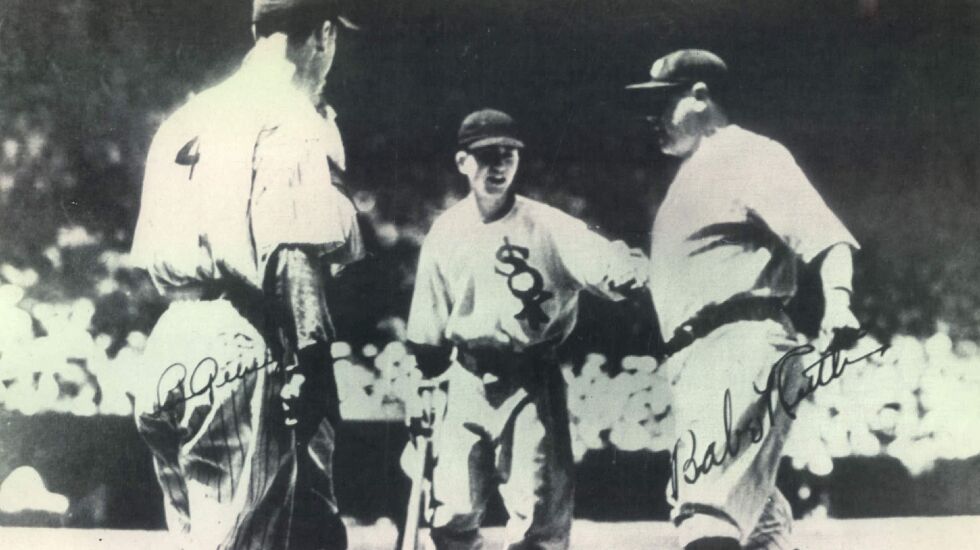

The 1933 contest featured such players as Babe Ruth, Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Gabby Hartnett, Carl Hubbell and Lou Gehrig. The American League was managed by Connie Mack, the National League by John McGraw.

There were no Black ballplayers in that first game or in any All-Star contest until 1949. Jackie Robinson did not debut for the Dodgers until 1947, then he played in six All-Star Games starting in 1949. There were four Black All-Stars in the 1949 game, including Larry Doby (Cleveland) and three players from the Brooklyn Dodgers: Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe and Robinson.

One prominent Chicagoan, Judge Kenesaw Landis, the first independent league commissioner, helped keep the entire league white. But another Chicagoan, visionary Bill Veeck, broke the American League color barrier almost single-handedly.

Before Robinson, the first Black player may have been William White, who subbed in one National League game in 1879. He only played once, and sources suggest he looked and identified as white, so his historic significance is dubious.

Moses Fleetwood Walker is generally credited as the first Black player to openly play in the majors. He appeared in 42 games for Toledo in 1884. In 1901, Orioles manager John McGraw tried to sign an excellent Black player named Charlie Grant by passing him off as Native American “Chief Tokohoma.” But Chicago’s Charles Comiskey recognized Grant and foiled the plan.

Landis was named league commissioner in 1921 following the Black Sox World Series scandal of 1919. He ruled with an iron hand, yet he insisted he never kept Black players out of the majors. Even though that’s just what he did.

In fact, no African Americans were signed until after Landis died on Nov. 25, 1944. Less than a year later, on Oct. 23, 1945, Branch Rickey announced the signing of Jackie Robinson to the minor league Montreal Royals.

The game changed forever in 1947 when Rickey and Veeck broke the color barrier for good. Rickey acquired Dodgers control in 1945 (along with Walter O’Malley and John Smith), then debuted Robinson, followed by the majors’ first Black pitcher, Dan Bankhead (1947), catcher Campanella (1948) and pitcher Newcombe (1949). The Dodgers proceeded to win six National League pennants and one World Series from 1947 to 1956.

Veeck grew up in Chicago baseball. His father was president of the Cubs when Veeck cut his teeth working Wrigley baseball jobs as a boy. After buying the Brewers minor league club and then selling it for a profit, he led a group that acquired the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) on June 22, 1946.

In 1947 he signed Larry Doby, who became the first Black player in the American League. In 1948 Veeck also signed legendary Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige who, at age 42, became the oldest major league rookie. A leading sports publication said hiring the Black Paige at 42 was just a publicity stunt. Veeck replied, “Had Satchel been white he would have been in the league 25 years ago.” Then Cleveland won the World Series that year.

Since the AL and NL teams had never played each other (and would not until 1997), that first All-Star contest was promoted as “the game of the century” to bolster Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair and to help uplift an America mired in the Great Depression.

The fans were allowed to choose the players, and Ruth garnered over 100,000 votes. The American League won, 4-2. Ruth had a home run, two hits and two RBIs. The Babe was no stranger to Chicago fans. Only months before, Ruth had smashed his storied “called shot” homer in Game 3 of the World Series at Wrigley Field. (Or did he call it?)

Eldon Ham is a member of the faculty at IIT/Chicago-Kent College of Law, teaching sports, law and justice. He is the author of five books on the role of sports history in America.

The Sun-Times welcomes letters to the editor and op-eds. See our guidelines.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.