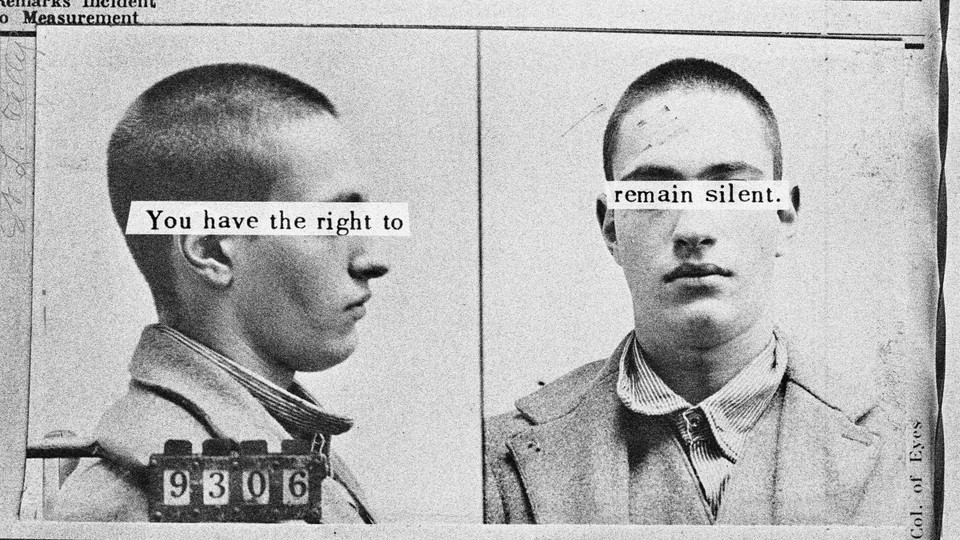

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.”

Deeply embedded in popular culture, those words can be recited from memory by generations of cop-show viewers. Yet more than 50 years after the Supreme Court ruled in Miranda v. Arizona that the Fifth Amendment requires police to inform people in custody of their rights, the promise of the decision remains largely unrealized.

Throughout two decades of reporting on patterns of police abuse in Chicago, I have again and again seen how fateful the first hours in police custody can be for those without competent legal representation—the problem Miranda was intended to address.

The embattled precedent—repeatedly scaled back over the years and now threatened by a Supreme Court majority that signaled its hostility in a decision last term—has had a strange career. While the practice of “Mirandizing” people in custody has been widely adopted by law enforcement, its actual impact appears to have been negligible. The reality is that people without means lack access to counsel, leaving them exposed to coercive interrogation techniques.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Chicago, the wrongful-conviction capital of the nation. But now, a consent decree—a judicial-enforced agreement resolving a legal dispute—entered in state court on Wednesday has set Chicago on a path that promises to give concrete meaning to Miranda and, in so doing, provide a model for other cities and states.

The decree resolves a lawsuit brought by civil-rights attorneys on behalf of protesters held incommunicado in the context of the 2020 George Floyd demonstrations and on behalf of the Office of the Cook County Public Defender, among other organizations.

As summarized by the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project at the University of Chicago Law School, who were part of the legal team that negotiated the decree, the Chicago Police Department will be obligated to provide every person in custody with prompt access to an attorney both over the phone and in person. Specifically, the department will be required to put phones and signs with the public defender’s free 24-hour hotline in every interrogation room; ensure every person in custody has access to those phones “as soon as possible,” and not longer than three hours, at most, after being taken into custody; provide private and confidential areas in every Chicago police station for people to call and to meet with lawyers; and give each person under arrest at least three phone calls in those first three hours of custody and an additional three calls any time they are moved.

This has the potential to right wrongs that have persisted for decades, during which the Chicago Police Department has maintained a practice of incommunicado detention, denying people in custody access to a phone, to counsel, and to the outside world, thereby creating a space in which police interrogators can exploit prisoners’ isolation and vulnerability. Case after case of wrongful conviction, costing the city hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements and awards, has revealed how those conditions are used by police to coerce confessions.

At the extreme, this practice has provided the setting for grievous human-rights violations, such as torture of suspects by officers under Commander Jon Burge, dozens of false convictions (many for murder) coerced by Detective Reynaldo Guevara, and the “black hole” at the Homan Square facility where thousands of people were held off the books without attorneys.

Such abuses notwithstanding, the practice of incommunicado detention is best understood not as misconduct—i.e., a violation of rules—but rather as de facto policy at odds with the law. In other words, this is the way things are done within the department. This is what officers are taught to do. And they can do so without fear of consequences, given the Supreme Court’s steady erosion of other protections for criminal defendants, such as the exclusionary rule, which was designed to deter abuses by excluding evidence obtained by unconstitutional means.

The upshot is that the overwhelming majority of those detained by Chicago police are denied access to a lawyer. A report issued by the Chicago Police Accountability Task Force in 2016 found that in 2014, just three out of every 1,000 people arrested by CPD ever gained access to a lawyer at any point in custody.

CPD’s arrest records reveal that between August 2019 and July 2020, more than half of the people detained in murder cases—in which the stakes of a false confession are highest—never made or were offered a single phone call, and those who were ultimately able to make a call waited more than 12 hours on average, during which they were vulnerable to CPD abuse. CPD has similarly denied phone access to people accused of lesser crimes.

The space where such abuses occur is both literal—the interrogation room—and a gap in the constitutional architecture. The Court’s landmark 1963 decision Gideon v. Wainwright established that the Sixth Amendment requires states to provide attorneys to criminal defendants unable to afford their own. A subsequent decision, Brewer v. Williams, in 1977, limited the scope of Gideon by holding that a defendant gains the right to an attorney “at or after the time that judicial proceedings have been initiated against him.” In other words, the first time an indigent defendant has access to a public defender is at their first court appearance.

Many of those held in custody thus lack access to a lawyer from the moment they are detained until they appear in court. Whether a matter of hours or days, that can be an eternity for an isolated individual subjected to coercive interrogation.

The intensely practical remedies of Chicago’s consent decree will finally make the promise of Miranda a reality in one of the largest cities in the nation. And they have implications beyond Chicago. As the country contends with a Supreme Court ready to set aside long-established precedents, the consent decree suggests possible strategies by which other cities and states can preserve, operationalize, and give concrete meaning to fundamental rights.