/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/b0c9c9774aca2fb620c2564d71b2a20b/0705%20Hill%20Country%20Floods%20BB%20TT%2015.jpg)

The National Weather Service issued cellphone alerts repeatedly in Kerr County as the Guadalupe River rose early Friday morning. Around the north and south forks that feed the river, forecasters triggered one push alert after another, according to PBS data.

The first went out at 1:14 a.m., then another at 3:35 a.m., then a third at 4:03 a.m. Then a handful more. “Move to higher ground now,” some of the alerts said. “Act quickly to protect your life.” At 5:34 a.m. and 7:24 a.m., more messages went to those along and down the river.

But the series of notifications was not enough to save more than 250 people who died or are counted as missing after the July 4 flood. A week after the tragedy, rescue crews continue scouring miles of riverbank and searching huge debris piles for victims.

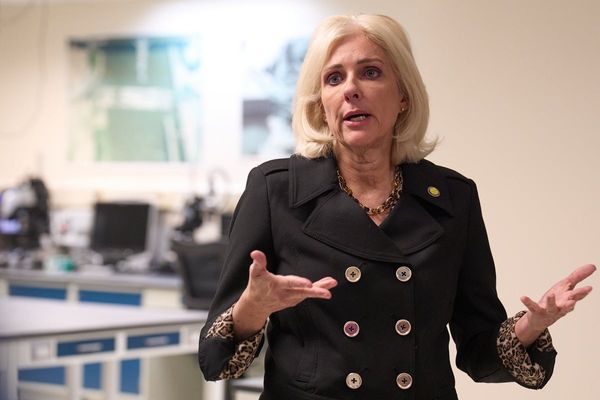

For warnings to work, people not only have to receive the alerts but they also need to understand how the warnings apply to where they are and know what to do about it — which is especially hard when it comes to flooding, said Kim Klockow McClain, a senior social scientist supporting the National Weather Service.

“We left way too much up to individuals to receive those warnings, know what to do and know where to even go,” McClain said, adding, “You need to tell people a little bit more.”

State legislators are searching for solutions to improve warning systems in places such as the Hill Country ahead of a special session later this month. The Texas House and Senate announced Thursday that they had formed committees to consider that and other disaster-related topics, starting with a hearing in Austin on July 23.

Lawmakers such as Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who leads the state Senate, have suggested the state should support the installation of warning sirens, a technology used decades ago to warn of air raids.

Researchers say there will be no single, simple fix.

Sirens can help in rural places where cell service is unreliable and phone alerts might not go off, according to researchers, but they are no silver bullet.

“Flash Flood Alley, from what I’ve read, that sounds like the perfect place to put sirens,” said Jeannette Sutton, a leading expert on warning systems and associate professor at the University of Albany. “It’s kind of remote. They know that there’s a high risk in that area.”

But, she added, “They can’t let it just be one solution.”

How sirens can help: They can be set up to trigger automatically if water reaches a certain height, which could require additional investment in flood gauges. This can be effective because it doesn’t require someone to be awake or rely on a judgment call on when to trigger them. There are also sirens that blare voice messages about impending danger.

But researchers emphasized that people may not hear sirens if they’re indoors during a heavy thunderstorm, and they need to be taught what the sirens mean when they go off, perhaps with signs in public places or pamphlets passed out to visitors when they check into a hotel or RV park.

A visitor from a tornado-prone area, for example, might run inside instead of fleeing to higher ground before a flood strikes.

Other states have already found ways to educate out-of-town guests about local hazards. McClain, the researcher who supports the Weather Service, pointed to the coasts of Oregon and Washington as places that have worked to prepare visitors for a tsunami with signage along evacuation routes and in hotels.

“Is it going to be perfect? Probably not,” McClain said. “But is it going to be better than doing nothing? Absolutely.”

Communities will benefit too from a culture of connectedness and readiness, said Rachel Hogan Carr, executive director at the Nurture Nature Center, which formed in Pennsylvania after repeated flooding along the Delaware River. Residents of a community need to know which neighbor or official they might call for help understanding what’s happening, and who can be relied on to go knock on doors or post on social media in a crisis.

“Those relationships can really make or break the response of a community,” Carr said.

"No one gold standard"

Flood warning systems need multiple layers, said Abdul-Akeem Sadiq, a professor at the University of Central Florida.

“There is no one gold standard,” Sadiq said.

Buildings in remote areas could have AM radios or weather radios, which are relatively inexpensive devices that broadcast warnings and could also help save lives. Local officials can record and send voice messages to television and radio stations. They can also transmit notifications through opt-in systems that can work via wi-fi — although opt-in rates for those are typically low.

“There are multiple ways that communication needs to be provided … and there’s multiple ways that the community members themselves need to be able to receive the information. So it is a two-way street,” said Eddie Bertola, who is the owner and founder Bertola Advisory Services and an expert on alerts and warnings.

But there are also a lot of issues to overcome.

Among them is the problem researchers refer to as “crying wolf.”

People get all sorts of warnings about disasters that never happen. Because of that, they might act more slowly when disaster actually strikes.

Sadiq said alerts need to become more specific to avoid reaching people who won’t be directly impacted. And if a disaster doesn’t happen, Sadiq suggested that officials explain to residents why it didn’t happen. Otherwise people will fill in their own reason, like thinking forecasters are incompetent, and can lose trust in forecasters.

Cellphone users also get every manner of alert: Texts. Calls. News blasts. Social media messages. Amber alerts that blanket the entire state. If they get too many alerts, Sadiq said, people may just switch them off.

The flip side, as Sutton pointed out: It’s safer to tell people they are at risk than not.

Some ignored alerts before flood

In the early morning hours on July 4, some in the path of the Hill Country floods did ignore the alerts.

Three-term Ingram city councilmember Raymond Howard lives on a block near the RV campground where at least 26 people disappeared, according to the Kerr County Lead, when the wall of water smashed through it. He said he ignored the first flash flood warning he got because he didn’t think it meant much.

“Like most people, I disregarded the first one, because we get them, you know, periodically,” he said.

But when he got the second warning, he said he got up, checked the radar and saw the massive rainstorm that seemed not to be moving. He knew that was serious. When the third warning came, he got out of bed, opened the door and saw water in the road.

He said he stuffed four of his six dogs into his car and ran down his block, pounding on doors to wake his neighbors. Then he doubled back for the remaining two dogs and drove to higher ground. He saw people in an RV, sinking into the water, yelling for help. He saw what seemed to be a teenage boy screaming as he was swept away.

Not far away, Jake Richard heard screaming outside of his RV in the early morning, he recounted in a post on X. He stepped outside and saw the swollen river gushing rapidly, washing away other RVs on lower land. He rushed back inside to wake up his wife, Julia Hatfield, to get to safer ground.

Richard began trying to wake up other neighbors by knocking on their doors — but all too soon, the water got too high to continue saving others.

“Houses and RVs from up river swept through the park,” he wrote. “We heard screaming and cries for help as families and children were taken by the waters. By the time we could locate them and try to find something to throw or provide help in any way, they were gone.”