In 1997, Gwyneth Paltrow made a request to Marie Claire that was outlandish even by Hollywood standards. The actor, whose star was then firmly in the ascendancy, if not quite at the ‘It girl’ levels it would reach later in that decade, had been approached to guest-edit an issue of the magazine. Her condition for agreeing? The publication would have to send her to a deserted island off the coast of Belize for three days, so that she could write about the experience. Paltrow packed just a few essentials – including a machete, a torch, and a few vegetables – and slept on the sand in the open air. When she swam in the ocean, she didn’t let a sighting of a nearby shark put her off – she “just knew” that it wouldn’t attack her. After all, she was Gwyneth Paltrow.

In the resulting diary-style article, which appeared in Marie Claire’s January 1998 edition, she wrote that her brief, self-inflicted foray into Robinson Crusoe territory had taught her that “I am stronger than I thought. I am braver than I thought”. This strange anecdote is one of many that have been excavated by Amy Odell for Gwyneth: The Biography, the former Cosmopolitan.com editor’s odyssey into the world of one of Hollywood’s most compelling but confusing figures.

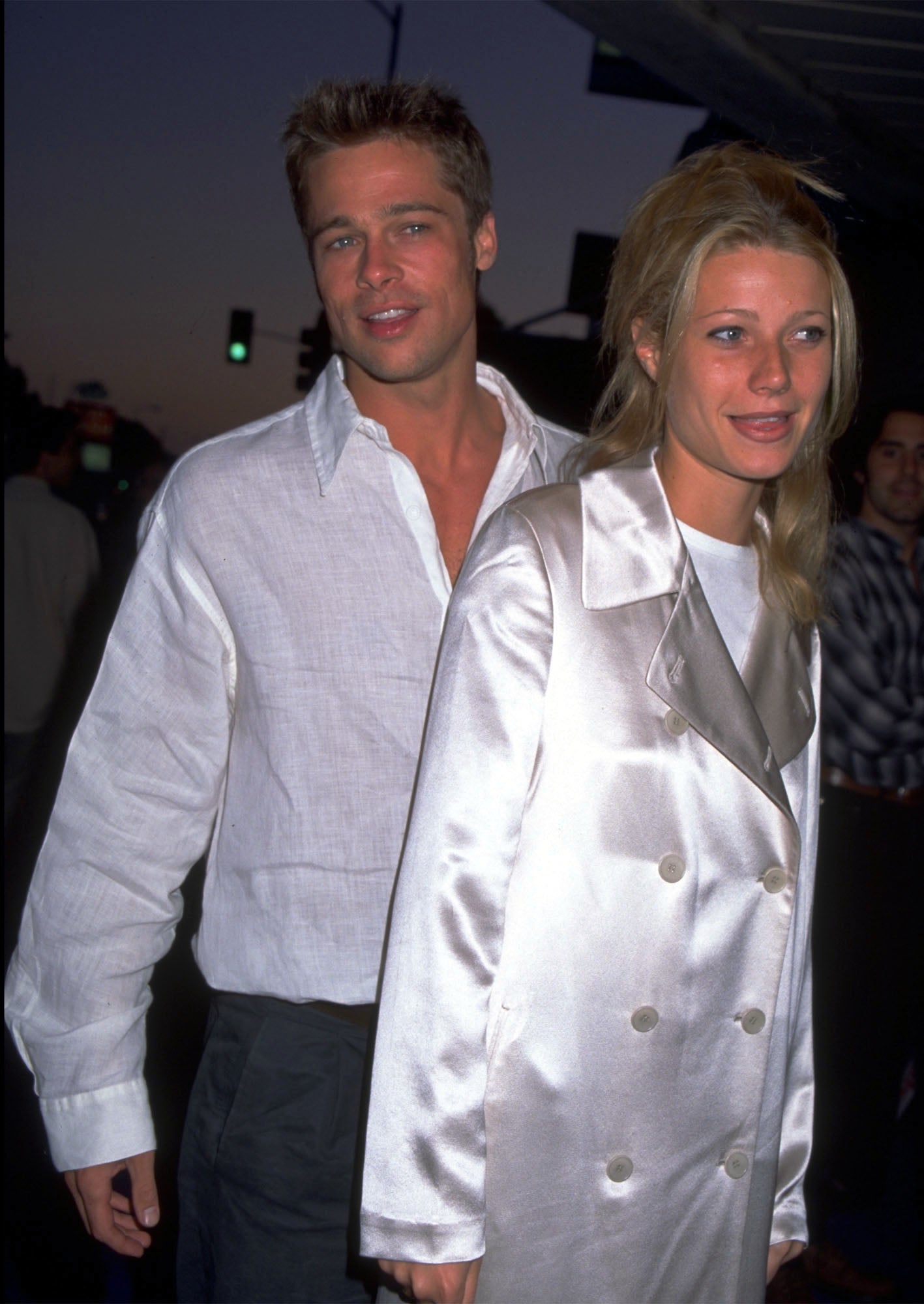

It’s also an episode that encapsulates the contradictions of the Paltrow persona, even before this persona was fully fleshed out in the public imagination. The actor, then best known for her lead role in Emma and her relationship with Brad Pitt, comes across like a hothouse flower with surprising resilience. She wants privacy (“I’m positive that there are no paparazzi out there, not that I wouldn’t put it past them,” she wrote) but seeks it through the medium of a publicity stunt. She allows us access to a vulnerability behind the ice princess image, but does so in a way that seems guaranteed to court hilarity rather than sympathy. The Miami Herald, Odell tells us, reported on Paltrow’s Castaway moment of clarity with the headline: “I am loopier than I thought.”

In this biography, Odell has the tricky yet quite delicious task of grappling with Paltrow’s many, often antithetical masks – and trying to work out what’s underneath them. At the start of her book, she foregrounds just how difficult it was to gain access to the “somewhat elusive” actor slash guru slash CEO slash walking self-parody. When Odell was writing her previous book on Anna Wintour, not exactly a woman known for being forthcoming, even the legendary Vogue editor-in-chief pointed her in the direction of potential sources.

Meanwhile, Odell claims that Paltrow’s publicist told her she would be “happy to help”, only for the vast majority of potential interviewees to “come back with a no or simply disappear altogether” after checking in with the star (who didn’t speak to the author for the book). This makes it all the more impressive, then, that Odell has still managed to interview more than 220 people. There are voices from Paltrow’s “childhood, her inner social circle, and the entertainment world”, as well as “current and former employees from Goop”, her infamous, vagina egg-touting wellness brand.

Nineties magazine profiles also prove to be a fertile source; they still have a sense of novelty because they predate digital media, and so haven’t been endlessly re-hashed elsewhere. In one snidey snippet from an old interview, Paltrow explains how she and her then-boyfriend Brad Pitt “had very different upbringings – when we go to restaurants and order caviar, I have to say to Brad, ‘this is beluga and this is osetra’”. She may still be something of a loose cannon, but it’s hard to imagine her trotting out this line now. The Gwyneth of 2025 would be savvier about her image, much better at toeing the line between knowingly ridiculous and obnoxiously snobby.

It’s easy to see how caviar might have been a casual fixture of Paltrow’s early days. After all, she is the daughter of Emmy award-winning actor Blythe Danner and successful TV producer and director Bruce Paltrow – as well as the goddaughter of Steven Spielberg, who she nicknamed “Uncle Morty”. Odell paints her as something of a golden girl from birth, a nepo baby before nepo babies started apologising for their celebrity parentage: “[Paltrow] may have noticed early on that the world was eager to give her what she wanted, and she didn’t need anyone’s permission to get it,” she writes. Take this tale, for example, which is just as illuminating as the desert island episode. Behind the scenes at a Massachusetts theatre festival with Danner, a young Gwyneth settles in the assistant director’s chair. That assistant director is then informed that they’ll have to sit at the back of the room instead.

With every other person seemingly falling over themselves to make the world a little easier for her, you see how Paltrow might start to cultivate the born-to-rule attitude of a young royal. The foundations are being laid for one of her future incarnations: the out-of-touch princess. “It wasn’t that Gwyneth didn’t try to understand average people,” Odell writes. “She simply had no point of entry into their lives.”

Odell manages to dig up some striking, gossipy details. In her school yearbook, Gwyneth’s classmates noted that her biggest nightmare was “obesity”. She has, apparently, always had a habit of miming vomiting behind the back of anyone she disdains. Pity poor Minnie Driver, then, who Odell claims fell victim to this while dating Matt Damon, best friend of Paltrow’s then-partner Ben Affleck. Damon’s next girlfriend didn’t fare much better in her eyes either, with Paltrow nicknaming one-time pal Winona as “Vagina Ryder”. There’s a brashness here that sits oddly with her princessy demeanour.

You see how Paltrow might start to cultivate the born-to-rule attitude of a young royal

By this point, Paltrow was settling into another incarnation, as the “first lady” of Harvey Weinstein’s independent production company Miramax. Here, we encounter yet more contradictions: Paltrow is at once portrayed as wildly ambitious (a trait inherited from her father, apparently) but also strangely unfussed by the business of acting itself. Perhaps, you wonder, this was a coping strategy when dealing with Weinstein.

After she earns her Oscar for Shakespeare in Love, yet more Gwyneths emerge: failed blockbuster star, tabloid hate figure of the moment and, later, wellness obsessive. Odell traces this particular interest back to her father’s death at the age of 58, due to complications from oral cancer and pneumonia; he passed away on a trip to Rome, intended to celebrate his daughter’s 30th birthday. Placed within the context of this family tragedy, you start to understand how alternative health fads might acquire something of an allure for Paltrow. It’s not only wealthy film stars that start desperately investigating all potential avenues, however dubious, when faced with a loved one’s illness.

But Odell doesn’t let her subject off the hook with pop psychology. The later sections are the book’s best, devoted to Goop’s controversy-laden rise from a lo-fi newsletter filled with rambling dispatches from GP (where she would eventually popularise the notorious phrase “conscious uncoupling”, in an email about her amicable split from Coldplay’s Chris Martin) to a headline-making business (Odell stresses, repeatedly, that it’s very hard to get details on how successful Goop actually is in business terms, but in publicity terms, it’s still killing it).

These chapters balance in-depth research with undeniably juicy reveals. Is this very wealthy actor really so tight that she asks each successive Goop food editor to cook her dinner, “under the guise of ‘recipe testing’”, as the book claims? (Apparently, said employee’s unofficial duties wouldn’t end there; on nights when Paltrow was apart from her second husband, Brad Falchuk, they’d have to drive the food over to his place.) And a section devoted to Condé Nast’s ill-fated foray into producing a Goop magazine, where the publishing house’s team of dedicated fact checkers find themselves attempting to corroborate some of the outlandish claims made by various spiritual healers and quacks, is darkly funny; it feels like the raw material for an HBO black comedy.

You do get the impression that, at least sometimes, Paltrow is in on the joke. She might genuinely “really believe” that Goop is “finally illuminating truths that other outlets would not”, as Odell claims she does, but she also seems aware that mockery can be lucrative. Like when she suggests that Goop’s travel app should be called “G Spotting”: “Everybody will make fun of me for being an idiot and we’ll have the ten thousand downloads we need right there.” She may be detached from reality, but she is not so lacking in self-awareness that she can’t use her various personas for her own benefit, knowing that we will all gobble up the woo-woo outrage bait. There’s a similar knowingness in a few of her more recent stunts, like her appearance in an advert for Astronomer, the company whose CEO and chief people officer resigned after being caught on a kiss-cam at a Coldplay concert.

But although Odell is adept at illuminating all these different sides of her subject, it’s still hard to get a proper handle on her. Who is Gwyneth Paltrow, really? The book can’t answer that, and I’m not entirely sure if Gwyneth could, either. But that image of a privileged woman decamping to a desert island, adrift from reality but convinced she is living authentically, certainly goes some way to do so.

13 actors who turned down movie roles – and then massively regretted it

Forget the haters, Dan Brown’s new novel will be an instant bestseller – here’s why

Dreaming of writing a book? This is the masterclass of how to do it

Is it the end for male novelists? The lonely life of a man writing fiction in 2025

Internet star Slutty Cheff on love and food: ‘Prioritise sex over everything else’

‘It’s like a second puberty’: Alcoholics on learning to live again