LOS ANGELES _ If California's revamped standardized tests are accurately measuring what they set out to measure, one thing is clear: the state has miles to go before all of its students are on an equal footing to face an economy that increasingly demands a college degree and stronger workplace skills.

The good news, if there is good news, is there's improvement over last year.

This is the second year the test results have been released to the public, and the first allowing for year-to-year comparison. Across the state, 48 percent of students met English language arts standards and 37 percent met math standards, according to the test results released Wednesday morning. That compares with 44 percent in English and 34 percent in math last year.

That means that more than half of the test-takers in each subject still fell short.

And even with the small improvements, certain groups of students continued to lag especially far behind. Only 18 percent of black students reached math goals in 2016 _ up from 16 percent last year but still far behind the 67 percent of Asian students and 53 percent of white students who reached that standard. Similarly, the percentage of Latinos who reached English goals grew by five points, but at 37 percent it was still significantly lower than the 73 percent of Asian students who did.

Students in the Los Angeles Unified School District had lower average scores but increased their scores slightly more than their peers statewide.

In California, 3.2 million public school students _ in grades 3 to 8 and 11th grade _ took the tests on computers starting in January. Called the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, the tests are based on a relatively new set of learning goals called the Common Core.

The standards being measured by the tests are much higher than those of previous state tests, where mere proficiency was enough. They're supposed to represent the knowledge and skills a student needs in order to be on track for their age to be prepared for college or work after high school.

"We're setting high goals," state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson said at a news conference Tuesday at Eagle Rock Elementary School in Los Angeles. "High expectations, high hopes, combined with resources, has made a difference."

"Is this where we want to be?" Torlakson said. "No."

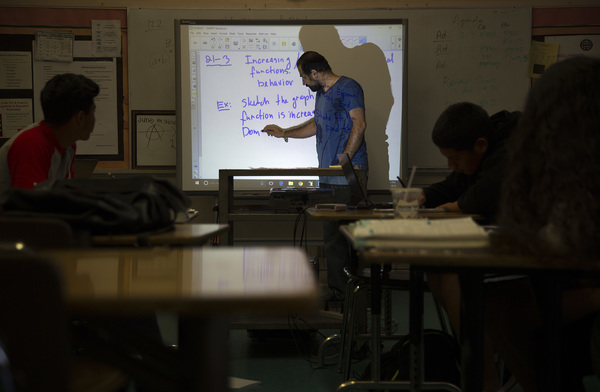

Many states have adopted the Common Core, or their own slightly edited version of the standards. They are more challenging, and are supposed to emphasize critical thinking and in-depth learning over rote memorization.

"This assessment is much more focused on higher-order thinking skills than the old California test," said Stanford education professor Linda Darling-Hammond, who helped develop the assessments, which are also known as Smarter Balanced, after the group that created them.

The tests are not supposed to be the sort that teachers can teach to in order to produce high marks _ a criticism of previous standardized tests.

One question Darling-Hammond recalled, for example, places the test taker in the position of a congressional staffer whose boss has to vote on whether to build a nuclear power plant. The student must use the Internet to find evidence for or against nuclear plants, and write a speech or memo using the search results.

Across the state, performance varied dramatically. The top-performing districts were wealthy enclaves such as Montecito, San Marino and Cupertino. The Saratoga Union Elementary district in Santa Clara, considered part of Silicon Valley, had top math scores, with 90 percent of students meeting or exceeding goals.

In the state's biggest district, Los Angeles Unified, overall standing in both subjects _ while showing improvement _ remained lower than the state average. Only 39 percent of L.A. Unified students met English standards and 29 percent met math standards, up from 33 percent and 25 percent last year respectively.

Black students in L.A. Unified had the lowest scores of any racial group and the smallest gains in both subjects, with 18 percent meeting math standards and 28 percent meeting English standards.

While some chalk up the educational achievement gap to wealth, poor black and Latino students fared worse on these tests than poor white and Asian students.

"This is shocking. It's not a pretty picture," said University of California, Los Angeles education professor Tyrone Howard. "We are not doing an adequate job educating poor kids, black kids, Latino kids."

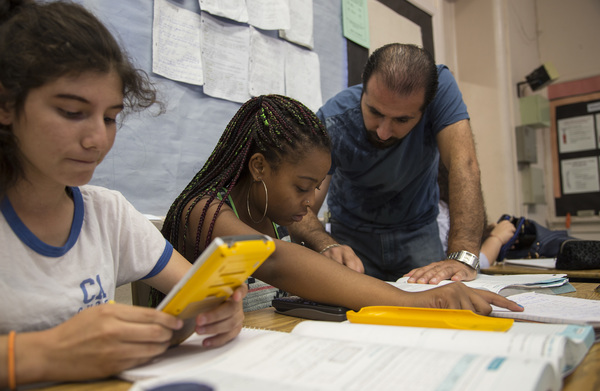

Howard said teachers often complain that with ever more rigorous standards, they continue to lack the training or support to teach underserved students effectively or to address the social-emotional issues, such as trauma, that can affect their learning.

The achievement gap, Torlakson said, is real. He said he has created a team to tackle the problem.

English learners also face serious challenges. In California, 13 percent of these students met English standards and 12 percent met math standards. In 2015, 11 percent of English learners met both English and math standards. In 2015-16, there were 1.37 million English learners in California, just over one-fifth of the total public school population.

Analysts say English-learner scores may be low in part because most of the tests are administered solely in English.

"We have a long way to go, particularly in mathematics," said State Board of Education President Mike Kirst. "The trend is up, but it certainly indicates that we have bigger problems in math than we do in English language arts. Even there, we don't have as many students college- and career-ready as we should."

California's gains were in line with the scores other states have posted, said Jacob Mishook, associate director of assessment and accountability at Achieve, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on learning standards. "The results in California are encouraging," Mishook said.

California, however, needs to invest more in education to raise students' performance significantly, said Carrie Hahnel, deputy director for research, policy and practice at The Education Trust _ West, a nonprofit advocacy group. The state, she said, only recently brought school funding back to pre-recession levels.