Pity internet users in the Middle East and Asia who have been forced to struggle either without the internet or with painfully slow downloads. The issue stems from a simple incident: the severing of two key internet cables that run beneath the Red Sea.

The cables are believed to have been severed by a liquified petroleum gas tanker, the ARD Horizon. Unlike some other similar incidents – such as the Baltic Sea outage last year, which was widely believed to be the result of Russian meddling – there is no suggestion of foul play.

“These are almost always accidents of some kind,” says Doug Madory, director of internet analysis at Kentik, which tracks internet traffic worldwide. “You have a lot of ships dropping a lot of anchors in shallow water. It's just a recipe for disaster.” But the incident highlights how precarious our internet connectivity is.

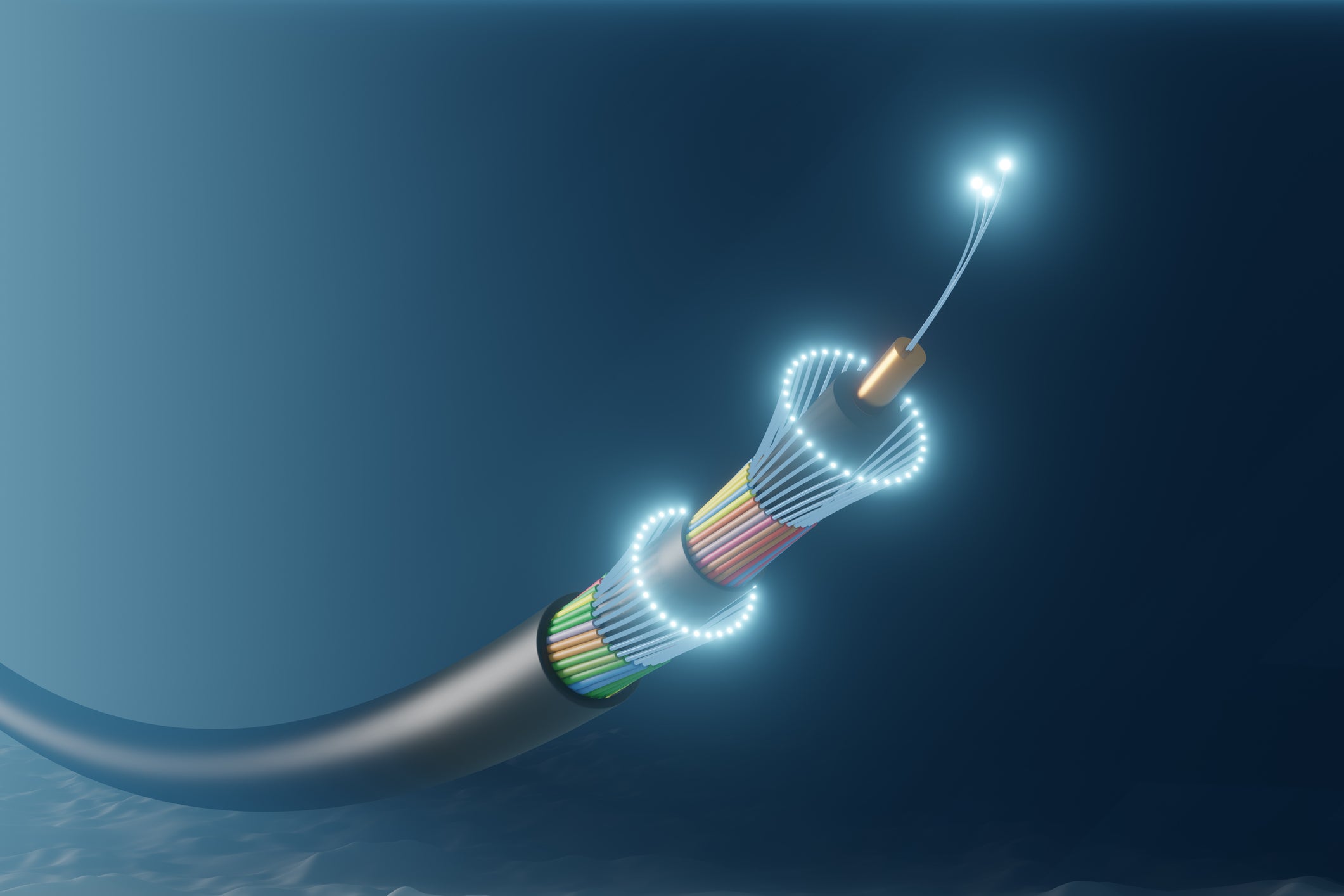

There are nearly 600 subsea cables strung around our planet, sitting on the sea floor, criss-crossing oceans for more than 1.5 million kilometres. These cables are the lifeblood of the internet, carrying data and website traffic around the web. Despite many people’s beliefs about the web relying on the cloud, the reality is that every website you visit or file you download or stream has to be fetched from somewhere – and 99 per cent of that intercontinental internet traffic is routed through subsea cables.

The cables are, at their thinnest, no thicker than a regular garden hose. And while they’re protected with metal sheaths designed to try and stop any accidental damage, the reality is that heavy cargo vessels and other ships traversing international waters can – by hook or by crook – end up damaging them.

“Cables go down all the time,” says Paul Brodsky, senior analyst at TeleGeography, an organisation monitoring subsea internet cables. In a given year, there can be up to 200 such incidents, the overwhelming majority of them accidental.

The problem is that if larger cables that carry vast volumes of traffic from one continent to another – trunk lines, as they could be described – are affected and there are few, if any, other lines that can easily route internet traffic from one place to another, issues occur.

In this most recent instance, most traffic to the Middle East and Asia passes through the SMW4 and IMEWE cables, meaning that when they’re cut, internet users have their internet requests routed through a circuitous route that causes latency, or delays. “We can see that all the clouds are experiencing increased latency as they’re rerouting traffic around,” says Madory. This results in patchy internet service and stuttering connections for end users.

It begs the question of why we’re content with a service often considered on par with running water, electricity and heat these days being so at risk from tampering or accidental damage. The reason is that usually, such outages can be quickly resolved. In fact, there’s an entire fleet of ships with repair equipment stationed around the world waiting to leap into action in the event of a cable break, in order to fix issues quickly.

The location of the Red Sea incident may not be as quick to fix, in large part because of the instability of the Yemeni government. A similar outage last year took a long time to resolve because “of all the chaos and uncertainty in Yemen,” explains Brodsky. Getting permits to access the waters under which the cables sit in order to fix them will likely be tricky this time around.

But more generally for subsea cables, there’s an acceptance that it’s a case of when damage is caused to them, not if. “It’s not so much preventing cable cuts or damage,” says Brodsky. “It’s about mitigating the impacts of them.”

One option to mitigate the impact of damage is to try and build in more redundancy to the network. What’s needed is “more cables, more routing diversity,” says Brodsky. “And trying to streamline repair procedures.” While the cables cost so much that only the largest internet and telecommunications companies can afford to install them, around 80 cables are currently in the planning phase worldwide, which would increase the number of cables serving the world by around 15 per cent.

Given the precariousness of subsea cables, one sensible solution that some people might point to would be to take advantage of the rise of satellite internet connections, such as Elon Musk’s Starlink constellations, which replace home internet connections with satellites that orbit the planet.

However, there’s a world of difference between servicing home users of the type that Starlink does, and scaling up to provide population-level coverage with the reliability needed. “Starlink is, for the most part, an access service,” says Brodsky. “It doesn’t really serve, in any form, as a substitute for long haul.” Brodsky points out that the only practical choice for widespread internet use is the subsea cable system we currently have.

He adds: “There is no technology out there that carries the sheer quantity of capacity that these summary cables carry.” Comparing the subsea cabling infrastructure with satellite connectivity gives some sense of the problem of scaling up satellite services like Starlink. “The entire capacity of the entire Starlink constellation is less than what you get on one submarine cable,” says Madory. “You can’t just replace one for one.”

It all means that for the foreseeable future, and until better alternatives can be found, we have to rely on the fact issues will continue to occur with subsea cabling – whether accidental or deliberate – and hope that they can be fixed quickly, or build backup routes along which traffic can be diverted. “The industry recognises this,” says Brodksy, “and governments recognise this too.”

Starlink down: Elon Musk’s satellite internet service confirms it is experiencing outage

Community Fibre down: Internet connections not working amid second major outage in a week

How viral man-hating memes went too far

I’ve swapped my jeans for ‘energy dressing’ – is it the key to a happy life?

I keep waking up at 4am. Is it stress, or is it the spirit world?