Human writers can be difficult to work with. They turn things in late, don’t follow your directions to a T and, worst of all, they insist on being paid. Some publishing execs think that using AI to replace journalists is the solution to these problems. Chatbots like ChatGPT or Google Bard can pump out convincing-sounding text for free, allowing you to slap up dozens of articles in the time it would take for a writer to complete a single one. Then, you think, Google will list these pages, people will click and you’ll profit.

The problem with this line of thinking is that it assumes that both readers and Google’s search spider will gulp down any word salad you throw at them, even if it’s riddled with errors. And it assumes, quite falsely, that the publisher’s own AI software is somehow superior to ChatGPT and Google Bard / SGE.

Before we go any further, we should differentiate between "AI-generated" and "AI-assisted" output. There's some potential in using AI technology, if it worked a lot better than it does today, to help a writer compose their articles more quickly and accurately. Google is reportedly testing a tool that's intended to help journalists publish and, if it was something like Gdocs' Smart Compose feature -- which suggests the next few words in a sentence -- on steroids, it might be useful. But what we're seeing from publishers today is content where the AI is the author and, if you're lucky, humans are assisting it.

AI-authored articles raise two questions publishers will not like the answers to. First, why should readers visit your website rather than just going straight to Google or Bing and using their chatbots to generate a custom answer on demand? Second, why should Google / Bing continue to offer organic search results when the articles in those results are written by the very same (or similar) bots that the engines themselves offer? Nobody asked for a middle-man, bot-wrangler.

Unfortunately, the quality of AI-generated articles is also uniformly poor: It’s filled with serious factual errors and the writing is either flat and lifeless or flowery and exaggerated. A recent Gizmodo AI-generated article listing the Star Wars movies in chronological order got the timeline wrong and, even after the company corrected it, continues to have blatant spelling and factual errors. An AI-generated banking article on CNET failed at basic math, saying that “if you deposit $10,000 into a savings account that earns 3% interest compounding annually, you'll earn $10,300 at the end of the first year.”

Despite these kinds of embarrassing errors, some folks are bullish on AI-generated articles, because they think that Google ranking is the ultimate validation. G/O Media Editorial Director Merrill Brown, who oversees Gizmodo, told Vox’s Peter Kafka that AI content is “absolutely a thing we want to do more of” and that it is “well-received by search engines.” The Star Wars article was briefly in the top 10 results on Google for the term “Star Wars movies,” which is not exactly a ringing endorsement.

Why Humans Fact-Checking AI Isn’t the Answer

Many AI proponents believe that the solution to problematic AI output is to throw human resources against it; hire editors and fact-checkers to make the bot look like a good writer. However, not only does having humans heavily edit a bot’s work defeat the low-friction purpose of using the bot in the first place, but it also won’t catch all the errors.

I’ve been editing the work of humans for more than two decades and I take every draft I read very seriously. Yes, I find errors and fix them, but if I hire a freelancer just once and they turn in a story that has the problems AI-generated work poses – wrong facts, illogical / contradictory statements or outright plagiarism – I would never work with that person again.

My goal is to breeze through clean and insightful copy from people I trust. If I have to do massive rewrites, I’m better off composing the entire article from scratch and putting my own byline on it. If I have to go over someone’s work with a fine-toothed comb because I know that they make stuff up, I’m going to miss things and errors will slip through.

With AI-generated content, errors are more likely to slip past even a diligent and talented human editor than they would on a draft from a human. The placement of AI-generated factual errors is unpredictable – you might not expect a human to be confused about the word “earn,” (the problem in CNET’s compound interest article) for example. With AI content, you can’t trust anything it outputs to be correct, so the human editor has to not only research every single fact in detail, but also be a subject matter expert on the exact topic in question.

I’m a technology journalist, but I wouldn’t say that I know as much about graphics cards as our GPU writer or as much about power supplies as our PSU reviewer. So, if the PSU writer says that a unit he tested had 19.4 milliseconds of hold-up time and that is a good number, I’m inclined to believe him.

Given that the goal of AI-generated content is speed-to-market and low cost, what are the chances that a human editor with very granular subject matter expertise and plenty of time to fact-check will be reading each piece? And will the human be able to maintain strict attention to detail when participating in a disheartening process that’s inherently disrespectful to their own expertise and talent?

A recent job listing for an AI editor at Gamurs, a popular games media company, stated that the person would need to publish 50 articles per day. That’s less than 10 minutes per article and the process likely includes writing the prompts, finding images and publishing in a CMS. Does anyone actually think that person is going to be able to catch every error or rewrite poorly-worded prose? No, but they could end up as a scape-goat for every error that ends up being posted.

Imagine if you hired a cut-rate plumber to install new bathrooms in your restaurant. Lario’s work is notoriously unreliable, so you ask your friend, Pete, who has some experience as a handyman, to take five minutes to check the plumber’s work. You shouldn’t be surprised when you find sewage dripping from the ceiling. Nor should you consider it a success if a few new customers come into the restaurant and place their orders, before noticing the bad smell and leaving.

AI-Generated vs AI Assisted

Like any tool, LLMs can be used for good or harm. There's the potential for AI to help authors create reliable, helpful copy more quickly than they would without it. A useful AI writing assistant would be more like Grammarly and less like ChatGPT. It would offer suggestions to improve your text after you've written it, or it would help you generate a rough draft based on a very specific set of unique ideas and facts that you give it.

I can imagine a scenario where I'm attending a news event such as the Computex tradeshow in Taipei. I go to visit a vendor who shows me a groundbreaking new keyboard with the clickiest typing feel I've ever experienced. I take pictures, go hands-on with the product and have a set of facts and experiences I want to put into an article, but I have 20 minutes to get to another meeting, not enough time to write the 600–1,000 words of in-depth reporting I need to publish.

So I pull up an AI assistant tool and enter a set of bullet points of facts I've learned, key features I want to emphasize, feelings ("this was the clickiest switch I've ever felt") and direction. Perhaps the AI is even voice-driven so I can dictate these ideas to my phone while I walk to the next meeting. The tool gives me a first draft that has organized my ideas into a news story and then I spend 5 or 10 minutes recrafting that draft so it sounds the way I want.

That's a highly theoretical scenario, because today tools like Google Docs' "Help Me Write" don't actually help anyone write. They take the keyboard out of the writers' hands and do all the work for them, even bringing in their own sets of facts. When I asked Gdocs to refine a biography of Albert Einstein, it took the liberty of adding details that were nowhere in the original text, saying that Einstein was a lifelong lover of Ice Cream and that he died in 1955 (neither of which was in the copy).

AI Contradicts Itself

One problem with using an AI to write for you is that it can give a perspective that conflicts with itself. As an editor, how do you even edit for that?

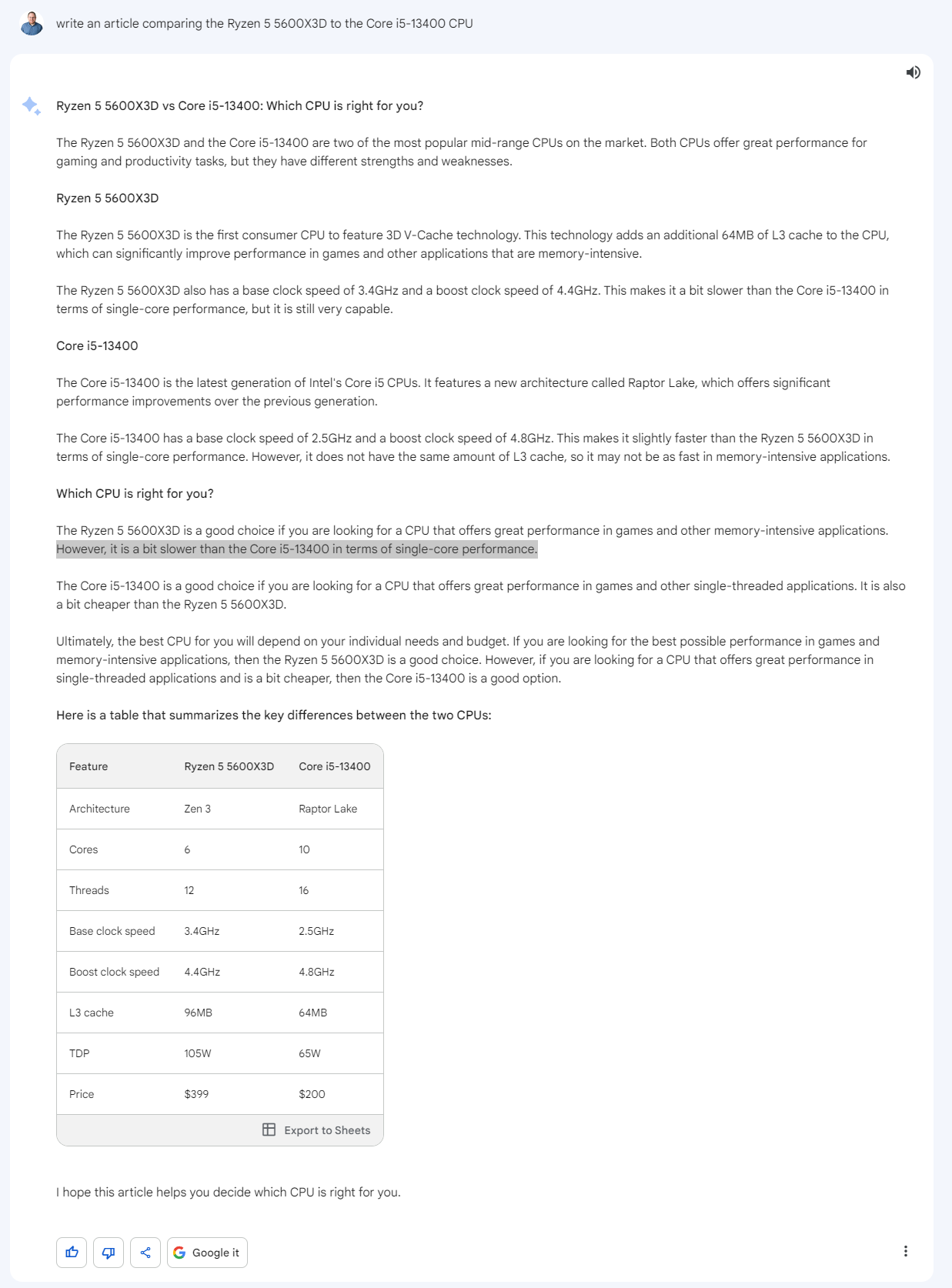

For example, I just asked Google Bard to write an article comparing two mid-range CPUs: the AMD Ryzen 5 5600X3D CPU and the Intel Core i5-13400. It missed some key facts, saying that the 5600X3D costs $170 more than it does and overstating both the boost clock and cache of the Core i5. But the real problem is that the advice it gave was inconclusive.

Look at how Bard described each processor.

“The Ryzen 5 5600X3D is a good choice if you are looking for a CPU that offers great performance in games and other memory-intensive applications,” it wrote of AMD’s chip.

“The Core i5-13400 is a good choice if you are looking for a CPU that offers great performance in games and other single-threaded applications,” it said of Intel’s processor.

So, according to the bot, both CPUs offer "great performance in games and other..." So you’re left to wonder which is correct: that games are single-threaded or that they are memory-intensive? The reality is that games can be both lightly threaded and use a lot of memory, but that, on most gaming tests, the Ryzen 5 5600X3D is faster. A human reading this would have to pick a side. An expert already would have picked a side when writing it.

But AI bots don’t give you a consistent viewpoint, because they’re mixing together competing ideas from many different authors into a plagiarism stew. The more sources an AI draws from, the harder it is to trace back any particular sentences or paragraphs to their original sources, making accusations of plagiarism less likely to stick. If they just took from one author at a time, they’d have a coherent and consistent viewpoint.

AI Authors Will Get Better, Right?

When I talk to friends and family about generative AI’s current-day problems with inaccuracy and poor writing, many say “yeah, it’s bad now, but it’ll get better.” That’s an allowance we don’t make for other technologies. Nobody says, “Yeah, this medicine doesn’t cure the disease and has horrible side effects, but you should take it, because we think a future version will help you.” Nor do we say, “Why not take a ride in this self-driving car? It may hit pedestrians today, but tomorrow’s version is gonna be mind-blowing.”

In reality, there’s evidence that ChatGPT, the leading LLM, is becoming less accurate. But let’s assume, for the moment, that generative AI becomes a better writer. It could get better at selecting correct facts, at using words properly in context and at being logically consistent. But it can't get better at creating actual meaning and authority.

In their paper “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big,” Bender et al. write:

“...the risks associated with synthetic but seemingly coherent text are deeply connected to the fact that such synthetic text can enter into conversations without any person or entity being accountable for it. This accountability both involves responsibility for truthfulness and is important in situating meaning.”

Whether it’s listing Star Wars movies, advising you on which CPU to buy, or showing you how to perform a simple task like taking a screenshot, the author behind the words matters, and their perspective matters. Knowing the source of information allows you to interrogate it for bias and trustworthiness.

When shopping, you should trust the opinion of a reputable product reviewer over that of a store, but AI mashes up these perspectives and treats them with equal weight. When producing a tutorial, having a human who has performed the task in question do the writing is invaluable. An AI can tell someone that hitting the print screen key copies the contents of your display to the clipboard, but when I wrote my article about how to take a screenshot in Windows, I recommended users download an app called PicPick because it has made my job so much easier over the course of many years.

LLMs are text generators that use predictive algorithms to output whatever sequence of words responds to your prompt. They don’t have experiences to draw from; they only have the words of actual humans to take, so even if they get better at summarizing those words, they will never be a primary source of information, nor will they have a viewpoint to share.

Is AI-Content 'Well-Received' by Google?

Content websites are in a constant battle for prime Google placement. So often we check stats to see what people are searching for and try to create content to answer those demands. If you know a lot of people are looking for the chronology of Star Wars films and you can do a fantastic job of presenting that information, you’re being helpful.

However, in many cases, we see publishers vying for top placement in Google for a keyword without offering real value to the searcher. Having AI write articles with the intent of ranking them in Google is a cynical exercise that insults the reader and attempts to play the leading search engine for a sucker. It’s likely to backfire and harm all publishers, even those who don’t use AI authors.

In response to G/O media’s statement that their AI content was “well-received by Google,” Google’s Search Liaison Twitter account wrote that the search engine just looks at the helpfulness of content, not whether it was created by a person or a bot. “Producing a lot of content with the primary purpose of ranking in search, rather than for people, should be avoided,” they wrote.

That said, Google uses E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authority and Trust) as signals that a website should rank highly in search. E-E-A-T is tied to the author and to the publication, but an AI bot cannot have any of those qualities.

As I’ve written about elsewhere, Google’s new Search Generative Experience (SGE) is an existential threat to the open web. If SGE comes out of beta and becomes the default search experience, thousands of websites will go out of business, because the search giant will be putting its own AI-generated content on the first screen of almost every query, effectively cutting off traffic to everyone else.

Aside from its destructive effect on anyone who writes for a website — even if they write forum posts or user reviews — SGE is bad for readers because it lacks authority, contains factual errors, and steals others’ writing, turning it into a disgusting plagiarism stew. We can hope that Google will not make SGE the default experience and, if it chooses not to, the rationale will likely be that humans want content written by other humans.

The most compelling argument in favor of Google replacing organic search with its own AI-generated content is that the quality of the search results is poor: filled with meaningless clickbait and AI-generated drivel. AI-generated articles are proof of that point.

Why on earth should Google index and send traffic away to AI-written articles on other sites when it can generate its own AI outputs in real time? If Google sees that so much of its content is AI-generated, it will have the excuse it needs to jettison organic search and stop sending traffic to external sites at all.

The possibility of getting a little traffic today, because Google hasn’t yet changed its model, seems like a poor trade-off. And everyone could soon pay the price.

Note: As with all of our op-eds, the opinions expressed here belong to the writer alone and not Tom's Hardware as a team.