English literary life has a peculiar resilience. Despite last year’s predictions of imminent meltdown, the global, new-look Man Booker prize (which is announced on Tuesday) is spookily similar to its old self. It has opened its doors to the English language novel in all its infinite variety. But it’s still Julian Barnes’s “posh bingo”.

On the credit side, it has not become a Yankee takeover. On the debit, the prize must now adjudicate so many discrete literary cultures that its choices will inevitably infuriate serious contemporary fiction readers.

No surprise then that, in this first year of Booker redux, the jury has played safe. Like the restored house of Bourbon, global Man Booker has learned nothing and forgotten nothing. From some points of view, the 2014 shortlist offers an anthology of Booker’s most seasoned lit-crit strategies from the fortysomething years of the prize’s history.

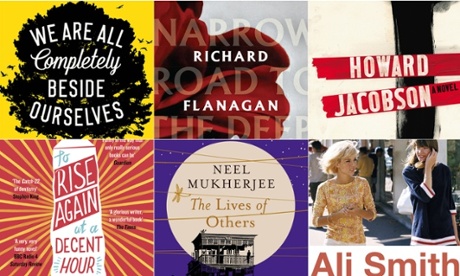

There’s a wild card, To Rise Again at a Decent Hour; a visceral Australian, The Narrow Road to the Deep North; and a masterclass in “literary fiction”, Howard Jacobson’s British dystopia, J. Then there’s a 500-page Indian novel (with a map), The Lives of Others, and – in an ecstatic postmodernist flourish – Ali Smith’s How to Be Both.

Finally, nodding to contemporary American fiction, there’s Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, the only shortlisted novel not to have been published by Random Penguin. That five of six finalists come from the same publishing stable is, perhaps, the only way this list breaks new ground. Bloomsbury, Faber, Profile, Sceptre and the rest are no doubt eating the carpet.

Alphabetically, then, what do we find? Joshua Ferris is young, brilliant and funny, an American writer with a unique voice who has been compared to Heller, Roth and Woody Allen. His Park Avenue dentist, Paul O’Rourke, a classic homme moyen sensuel, suffers a disturbing online violation of his privacy that begins with comic mayhem and ends with life, death, the universe and everything. To Rise Again at a Decent Hour (Penguin), the most entertaining book on this list, and possibly the most accomplished, probably won’t win, for three reasons: it’s light, funny and American. Man Booker doesn’t do funny/light and now, having gone global, will want to persuade us that this does not mean creeping Americanisation.

In the old days, when Thomas Keneally and Peter Carey were winning this prize, Australian fiction seemed to hold a long-term lease on the shortlist. Richard Flanagan, a big hitter from Down Under, renews this connection with The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Chatto), a dark, compelling novel about the Australian experience of the Burma railway. Through the character of Dorrigo Evans, Flanagan makes imaginative use of some harrowing material, cleverly linking it to a poignant love story.

The other American contender, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves (Serpent’s Tail), is an oddity. In a year that brought some important new US fiction (Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens, Akhil Sharma’s Family Life and Robin Black’s Life Drawing), how this could be selected is a mystery. Suffice to say, its appeal turns on a single, outrageous narrative twist. Some readers will love it, but Man Booker is still struggling to accommodate our American cousins.

And so, thankfully, we come to Jacobson and his powerful British dystopia, J (Cape). Jacobson is renowned for dark humour and a ferocious intelligence that takes no prisoners. It was not until he won the Man Booker in 2010 with The Finkler Question that his Jewishness was fully acknowledged. The upshot of that success is a post-apocalyptic love story, with a quasi-Jewish subtext. Kevern “Coco” Cohen loves Ailinn Solomons. Both live in a nightmare future world – it’s not clear where exactly, but a place not unlike Cornwall. Each is tyrannised by the past, which conceals a catastrophe that’s only referred to as “what happened, if it happened”. Why, when characters utter a word beginning with “J”, do they mime zipping the lips? Jacobson tantalises the reader with many other puzzles. This menacing vagueness, provoking myriad questions, is not fully answered, perhaps because Jacobson cannot acknowledge a Jewishness that might imprison his imagination. J, however – a mighty novel that has been compared to Brave New World and 1984 – remains a strong contender.

It is more than matched by a fine Indian novel in the Man Booker tradition. Neel Mukherjee is the highly accomplished author of A Life Apart. In The Lives of Others (Chatto), his second novel, he juxtaposes the traditional Indian family life of late 60s Calcutta with the political crisis of West Bengal. Supratik Ghosh has rejected his family to engage with extremism, a challenge that sponsors a succession of shocks to the order of things. Apart from its impressive grasp of the revolutionary mind, The Lives of Others paints an affectionate and complex picture of a society on the brink of change. It is vivid, passionate and rich with a strong claim on the judges’ sympathy.

At the end of How to Be Both (Penguin), one of the protagonists declares: “I’m so, so tired of what stories are meant to mean.” This might be Ali Smith’s credo. She’s an exhilarating writer of profoundly innovative new fiction. Her unbroken text offers two linked stories, braided together, that challenge conventional ideas about character and narrative. The tale of a teenage girl named George, who is coping with the death of her mother, is spliced with the true story of Francesco del Cossa, a Renaissance artist. Cossa’s haunting Ferrara frescoes inspire a final quest for meaning by George and her mother that begins with tourism and ends with the transcendent mystery of love and loss.

Smith is a writer like no other at work today. If she were to win this prize, she would delight her many fans – for whom she is among the best there is – while exhilarating and possibly baffling a whole new generation.

Will it be Jacobson, Mukherjee or Smith? They all compete at short odds. You pays your money and you makes your choice.

To buy any of these titles at a special price, go to bookshop.theguardian.com