On Sunday 27 July, the world’s best professional cyclists will arrive at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, crossing the finish line of the 2025 Tour de France and concluding the three-week-long race across the Hexagon.

While the Tour de France represents one of the most challenging and thrilling sports events in the world, its name is also associated with one of the biggest doping scandals in history.

In 1998, Willy Voet, a staff member of the Festina team competing in the Tour, was stopped at the Franco-Belgian border and found with performance-enhancing drugs in his car.

At the time, doping was already known to be widespread in sports. Sprinter Ben Johnson had already been stripped of his Olympic gold medal in 1988 after testing positive for a banned anabolic steroid.

But the Festina affair was different: it involved police, judicial authorities and cast doubt on the integrity of the Tour de France. The affair was so impactful that it led to the creation of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 1999.

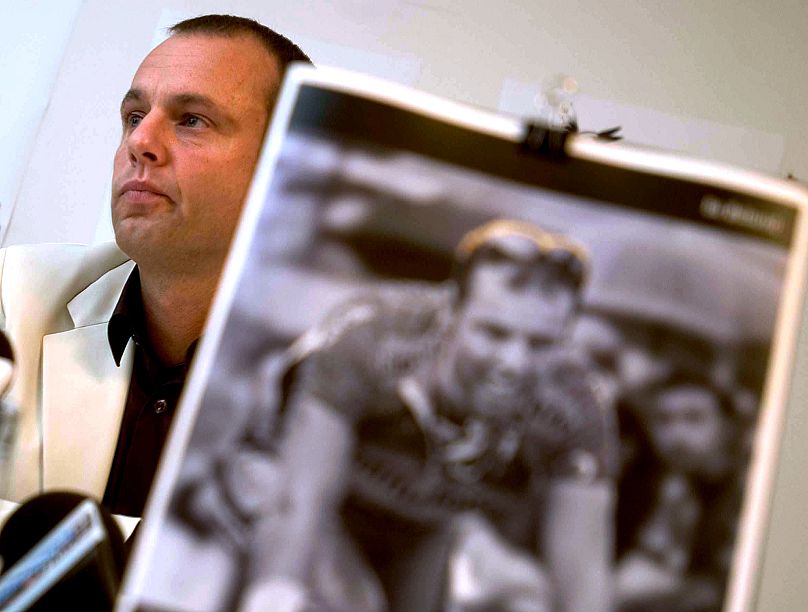

In the season finale of Euronews Tech Talks, we talk with former professional Danish cyclist Bo Hamburger, who raced in the Tour in the 1990s and early 2000s and used performance-enhancing drugs for eight years. With him and other experts, we explore why athletes dope and the effects of doping substances on their bodies and minds.

‘I needed to be part of the game’

Bo Hamburger became a professional cyclist in 1991. In 1994, he won a stage of the Tour de France and was on an upward trajectory, until injuries during the winter of 1994–1995 delayed his preparation.

“I went to Giro d’Italia in 1995 to prepare for the Tour de France, which was again my main goal, and I couldn’t follow the peloton,” Hamburger explained.

This realisation led Hamburger to ask his doctor for help. “He told me there was EPO, and I immediately said: ‘how can I get it?’”

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hormone that stimulates the production of blood cells, enhancing endurance. Thanks to this capability, EPO was widely used in professional cycling during the 1990s and 2000s, leading to major scandals like the Festina affair and Lance Armstrong’s case.

Bo Hamburger started using it in 1995 and continued until 2003. “It was my decision, there was no pressure from the team,” Hamburger said. “From my point of view, it was a no-brainer, I needed to be part of the game”.

The experience of Hamburger aligns with the findings of Christophe Brissonneau, a researcher in the Sport and Sociology department at the Paris Cité University. According to Brissonneau, the use of pharmacology, whether licit or illicit, was not driven by a desire to cheat. Rather, athletes saw it as a way to recover from injury, manage the fatigue caused by intensive training, and perform at their best.

“You could train harder, recover a lot faster. You could train more days in a row at a high level and eventually increase your performance. But it was still the same pain in the legs and the lungs,” Hamburger explained.

The potential physical cost of doping

Bo Hamburger told Euronews Next he did not experience any specific health issues related to his EPO use.

“I couldn't do the same speed on the bike and all these things, but inside me, there was nothing [that] changed. I went back to normal and also today, I feel healthy, but that's not an excuse to take it,” he said, commenting on when he stopped using EPO.

Research also struggles to fully assess the long-term health effects of performance-enhancing drugs. Dominic Sagoe, Professor of Psychology at the University of Bergen in Norway and founder of the Human Enhancement and Body Image Lab, explained that doping is still a relatively new field of study, often involving newer substances, so data is limited.

April Henning, associate professor of international sport management at the Edinburgh Business School, Heriot-Watt University, also underlined the difficulty of linking substances to long-term health outcomes.

“Research does show that particularly with steroids, there can be quite severe side effects with long-term use, and sometimes even with short-term use. But we also know that there are lots of athletes who have admitted to using doping substances, who decades later, don't seem to have felt any ill effects from that,” she said.

“We can't know everyone's medical history; we cannot know what's going on,” she continued, suggesting that major health problems often depend on multiple factors.

Still, Sagoe noted that anabolic steroids have been linked to heart attacks, liver damage, and a thinner cerebral cortex, while EPO is associated with the risk of stroke.

Mental health effects of performance-enhancing drugs

Bo Hamburger doesn’t recall experiencing any mental problem due to his use of EPO. However, he does remember one mental coping mechanism he used at a critical moment in his career. “I took EPO and the test discovered that I took it, but I was not feeling guilty of the crime they accused me of,” he said.

Sagoe explained this as a common cognitive mechanism for people using performance-enhancing drugs. “The dissonance is what, in a way, reinforces the use. The person downplays the negative effects in order to justify continuing,” he told Euronews Next.

Sagoe added that steroids are linked to depression and aggressive behaviour, while the mental health effects of EPO are less studied. The picture is further complicated by the fact that athletes often combine substances, making it difficult to isolate the effects of a single drug.

Bo Hamburger spent many years of his professional cycling career using EPO and lying about it. Now, he’s open and honest about his experience.

“We also need to talk about these things, not forget about it because history seems to repeat itself when you try to hide it,” he said.