War In Europe. The China-Russia Alliance. De-dollarization. How $47 billion Citadel is making the best out of the worst of times.

by Maneet Ahuja and Chris Helman

Ken Griffin is staring pensively out a wall of windows on the tenth floor of a Midtown Manhattan office building, one of three locations in New York City occupied by his $47 billion Chicago-based hedge fund, Citadel. It’s early March. Vladimir Putin’s mechanized assault on Ukraine has stalled; he’s now making veiled threats about nuclear strikes. From Griffin’s vantage point there’s no mushroom cloud on the horizon, but the prospect is deeply worrying to the financier.

“I grew up in a world where we were children of mutually assured destruction,” says Griffin, 53. “It was ‘get under your desk to brace for the impact of a nuclear blast.’ To see us return to the rhetoric of that moment is a huge setback.”

The S&P 500 has fallen 12% year to date. European stocks and the Nasdaq are down nearly 18%. Oil prices are surging. This flurry of bad news is coming hot on the heels of a stellar 2021 for Citadel, a year when the hedge fund gained 26% and Griffin personally earned $2.5 billion. He’s now worth $27.2 billion, but he has bigger things on his mind than the size of his personal fortune.

“The continued unfolding of this catastrophe in Ukraine is a giant unforced error by mankind,” he says. In hindsight, maybe it wasn’t a great idea for Ukraine to have taken America’s advice in the 1990s and returned its nuclear weapons to Russia after the Soviet Union’s collapse. With NATO countries reawakening to the existential threat Russia poses, Griffin points to the obvious beneficiaries of rearmament, namely defense and energy stocks—both already trading at elevated levels.

But that’s short-term thinking. Longer term, Griffin sees a flock of black swans looming. He predicts that the severity and character of the sanctions the West has imposed on Russia will have a long-lasting impact on the dollar-based global financial system. The unprecedented moves by Western powers to shut off Russia’s access to capital markets heralds the weaponization of the dollar, he says.

There will be serious repercussions, with Russia, China and others seeing no option but to diversify away from the greenback. De-dollarization by a China-Russia-Iran-Brazil trading bloc could easily morph into the exclusion of American companies and investors from fast-growing markets. “Have we laid the seeds for the setting of the American era of technological superiority?” Griffin asks.

It’s worth listening to him. Griffin is a big-picture guy whose track record is nearly unparalleled on Wall Street. He’s had only two down years in the past 31, earning his investors an average of 19% per annum. What has driven those returns is his close study of macrotrends and his uniquely powerful position at one of the fulcrums of global finance.

Citadel Securities, Griffin’s other business, is one of America’s largest market makers. When it comes to equities, the firm accounts for more than 25% of all U.S. trades, 40% of retail trades and more than 30% of stock options volume. Griffin employs smart mathematicians and scientists who harness cutting-edge technology—predictive analytics, machine learning and artificial intelligence—to analyze huge amounts of data in real time. As a result, Citadel Securities is expanding into new markets and growing more rapidly than Griffin’s hedge fund.

Though it collects a fraction of a penny per share on each trade, Citadel Securities brought in $7 billion in revenue in 2021, and for the first time Griffin agreed to share part of his empire with outsiders, selling a 5% stake to two blue-chip venture capital firms, Sequoia and Paradigm. The investment valued the brokerage at $22 billion, increasing Griffin’s net worth by $5 billion in the process.

The investment by Paradigm, which specializes in crypto, underscores Griffin’s intention to become a leading market maker in the fragmented but fast-growing cryptocurrency trading business. Citadel Securities is run by a Beijing-born data genius named Peng Zhao, 40. Zhao, who has a doctorate in statistics from Berkeley, is well equipped to lead Citadel’s charge into digital asset trading.

In casino terms, Citadel Securities is the house. It doesn’t matter if markets go up or down. As long as people are trading securities, Citadel takes its profit. Its lifeblood is volume, and despite Griffin’s consternation over the consequences of war in Europe, he knows that uncertainty and tumultuous markets will almost surely add to his billions.

“The businesses he’s built, my gosh, it’s breathtaking,” says billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones. Adds another billionaire investor who wishes to remain anonymous: “Griffin has reduced the cost, processing and deployment of technology so that it’s very, very hard for others to compete with Citadel.”

Growing up in South Florida in the 1980s, Griffin was drawn to tech from an early age. An honor student at Boca Raton Community High School, he was a computer whiz and president of the math club. He had a part-time job at IBM as a teenager and also started a software business that sold educational programs at a discount to professors. Entrepreneurship was in his blood. His maternal grandparents ran a thriving regional fuel-oil company in Illinois, plus three farms and a seed business.

Griffin says he made his first stock market windfall trading on advice he learned in the pages of Forbes. It was 1987, he was a freshman at Harvard and he had read an article casting doubt on a high-flying new company called Home Shopping Network. He bought put options, betting that the stock would fall, and made a few thousand after it collapsed. He later installed a satellite dish on the roof of his dorm so he could pipe real-time quotes directly into his IBM PC.

There will be serious repercussions to the weaponization of the dollar. “Have we laid the seeds for the setting of the American era of technological superiority?”

As an undergrad, Griffin traded options and convertible bonds with $265,000 in capital from his family and friends. His negative bets paid off so well in the aftermath of the market crash of October 1987 that upon his graduation two years later, Frank Meyer, owner of Chicago’s Glenwood Capital, staked him with $1 million. He posted a 70% return in his first year. In 1990, at age 22, with additional backing from Meyer, Griffin launched what would eventually become Citadel Investments, an early “quant shop” with one computer, two employees and $4.6 million in funds.

Citadel’s returns were stellar from the start, averaging 42% in his first two full years trading. By the time Griffin was 30, in 1998, Citadel’s hedge funds had $1 billion in assets. In 2002 he created Citadel Securities partly because he was miffed that the broker-dealers handling his options trades were charging stiff commissions. In 2003, at 34, Griffin debuted on The Forbes 400 as that year’s youngest self-made member, with a net worth of $650 million.

Over the years, he has made opportunistic acquisitions. In 2002 he picked up pieces of Enron’s energy trading arm, and four years later he snapped up Amaranth Advisors and Sowood Capital after they suffered devastating trading losses. It hasn’t all been a smooth ride, however. The 2008 financial crisis hit Citadel’s flagship fund with 50% losses, bringing the firm dangerously close to failing. He called his move to halt redemptions “one of the most difficult decisions I ever made.” The next year he recovered, up 62%.

Ask him for the key to his success and he’ll talk about his obsession with talent. He reckons he has personally interviewed no fewer than 10,000 candidates—roughly two per day—over his career. In just the last three years, Citadel has hired more than 400 engineers, some fresh out of elite colleges but others from competing Wall Street firms and big tech.

Citadel has an intense “sink or swim” culture. “My reputation at Goldman was that I was a little too detail oriented . . . managing too closely some of the people,” says Pablo Salame, Citadel’s co–chief investment officer, who was Goldman Sachs’ vice chairman before joining the hedge fund in 2019. “Then I realized I’ve been way too big-picture. Being in the weeds—Ken redefined it for me.”

Griffin has spent most of his career avoiding publicity. But last year, Citadel Securities’ close relationship with commission-free brokerage firm Robinhood unleashed a storm of unwanted attention. In a practice known as “payment for order flow,” Citadel pays Robinhood for millions of buy and sell orders each day, then uses its massive computer power to match the trades in a way that earns it virtually risk-free profit. The practice is legal—and it’s how Robinhood can afford to offer commission-free trades—but many consider it unsavory.

In February 2021 Griffin was hauled before Congress to testify in hearings concerning a halt in trading in GameStop, the poster child for the “meme stock” frenzy roiling Wall Street at the time. An army of unsophisticated traders, mostly from Robinhood, were bidding the past-its-prime video game retailer to unprecedented heights and, in the process, catching some pros with their pants down. New York City–based hedge fund Melvin Capital was caught in a short squeeze and nearly forced to liquidate. Griffin’s hedge fund and Steven A. Cohen’s Point72 saved Melvin with a $2.75 billion emergency investment.

A few days later, Robinhood made it impossible for its customers to buy meme stock shares, which in addition to GameStop included struggling movie theater chain AMC and big box retailer Bed Bath & Beyond. The price of GameStop plummeted, effectively throwing Melvin another lifeline. After investors filed numerous lawsuits and the SEC launched an investigation, Griffin told Congress under oath that he had no communication with Robinhood. Citadel and Robinhood were cleared of conspiracy charges, but Griffin became the subject of relentless ridicule in memes on Reddit and Twitter.

“The vilification of payment for order flow might score political points. But what a disgrace if it detracts from retail investor confidence in the stock market and the allocation of capital to companies that create jobs,” Griffin says. “When I was in college, trading commissions were $19 or $20. Today they’re free. I mean, the amount of value that we have shifted to retail investors has been stunning—and my firm has been one of the biggest drivers of that phenomenon.”

During the pandemic, Griffin donated more than $50 million to vaccine development and other Covid-19-related programs. Like some other Wall Streeters, he set up operations in Florida, with a makeshift trading floor for 50 key staffers and their families at the Four Seasons in Palm Beach—near the 20 oceanfront acres he has accumulated half a mile from Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago.

In June 2021, Griffin ordered most of his 4,000 employees back to work. “One of the biggest drivers of our success was our decision to return to the office,” he says, contending that in-office work shows respect to his fund’s clients. “There’s no doubt that the collaboration amongst my colleagues in person accentuates our ability to act and react to information in a way that a number of our competitors just can’t.”

The war in Ukraine has pushed aside pandemic and meme stock woes. Like any great trader, Griffin is focused on domino effects. In other words, he’s interested in how the reaction to one disaster reduces the number of good options available for dealing with the next one. He bemoans America’s economic response to the pandemic—essentially flooding the zone with $5 trillion in federal stimulus spending. “It has put a great burden on our fiscal deficit and locked in a huge liability for the next generation. As fiscal spending fades away, what will be the intrinsic economic growth that we’re going to experience?”

Trading Juggernaut

Thanks to superior technology and talent, Griffin’s market maker, Citadel Securities, dominates nearly every market it’s in. What’s next: Crypto trading and, eventually, an IPO.

Stimulus also contributed to inflation, currently running at 8%. “In our adult life, we’ve never really experienced inflation,” Griffin says. “We don’t think about having to negotiate multi-year wage deals with locked-in wage increases.”

Griffin believes inflation is going to force central banks around the world to tighten interest rates more aggressively. That doesn’t bode well for Europe, where a record price spike for electricity and natural gas (to more than 10 times U.S. prices) is already hampering the production of things like chemicals and gas-derived fertilizer.

Perhaps the biggest risk, Griffin says, is the weaponization of the dollar now that Western powers have cut off Russia’s access to bank accounts containing hundreds of billions of dollars in cash and securities.

“Putin refers to it as an act of war,” he says. “Our nation has a huge debt to finance. And if we see key buyers around the world back away from owning Treasuries and other dollar assets, we will pay a much higher cost on that debt for years to come. It will take away from our ability to provide a social safety net, our ability to invest in research and development and to invest in education or infrastructure.”

It’s already happening. In late March Russia demanded that Japanese fuel buyers pay in rubles. How long before China is paying in yuan instead of dollars? “Nations won’t want to depend upon the good graces of America.”

That’s just the first-order effect. He thinks it will get worse. “There’s nothing like the need to drive innovation.” Denying rival nations like Russia and China access to American technology will simply lead them to find other solutions. “Creating independence from the U.S. on high-end technology has become an existential issue, because they cannot rely on us.”

It’s baffling to Griffin that America, with plentiful natural resources, is not self-sufficient in oil. “This is a form of inflation self-imposed by our policy decisions in Washington,” he says. “We are blessed to have such deep reservoirs of energy in America—the combination of fossil fuels, oil, natural gas and the [large size] of our country to avail ourselves of solar and wind. It is completely unacceptable for our country, with all our technological and geological advantages, to depend on any other country for energy.”

Despite the dark clouds, Griffin doesn’t think investors should be freaked out by the surge in commodity prices. He has faith that those price spikes will ultimately resolve themselves. Consider natural gas, which just 15 years ago was expensive and in short supply. Then came the fracking revolution, and now American gas is so cheap and plentiful that the U.S. exports 7 billion cubic feet of it per day to Europe, displacing Russian gas.

Griffin points out that “commodities typically have become dramatically cheaper over the course of history as we have found solutions to either secure them at a lower price or find a lower-cost solution.”

The best long-term bets, he says, are innovative, fast-growing American tech companies “on the forefront of revolutionizing how corporate America functions.”

As for bitcoin, Griffin the investor is still a skeptic. “There’s nothing efficient about bitcoin from an economic or environmental perspective. I don’t see bitcoin as a payment solution,” he says. “I personally haven’t seen the attraction of owning cryptocurrencies as a store of value. But you know, there are assets I own that people would make the same arguments about. I’m a collector of American abstract art.”

But Griffin the shrewd business strategist can’t resist training his genius quants at Citadel Securities, with their market-dominating algorithms, on the $2 trillion market for trading cryptocurrencies. After all, if making money off Robinhood traders has been easy, profiting from rubes who have given Dogecoin a market cap of $20 billion should be a snap.

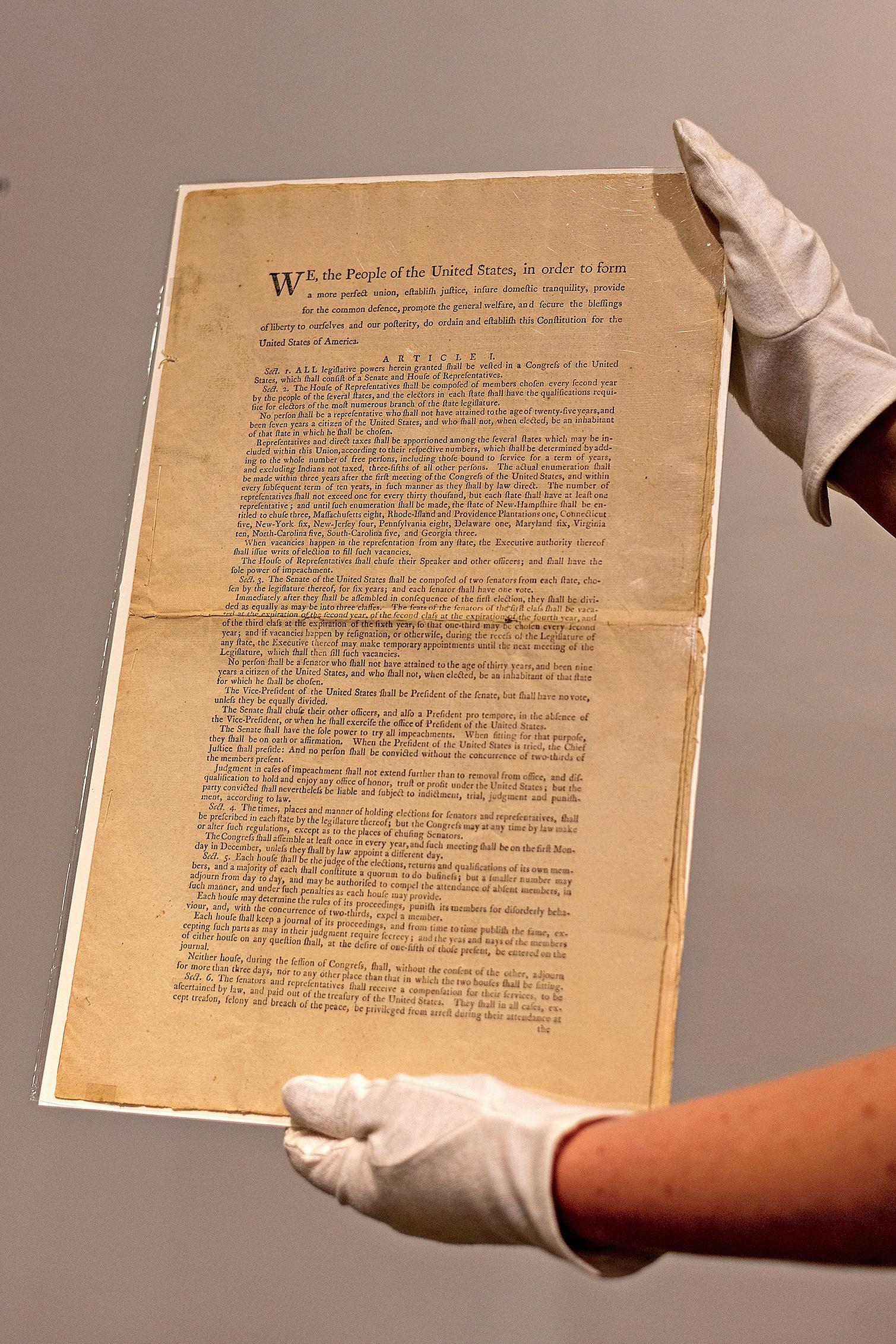

Griffin has already bested the crypto crowd with his recent $43 million purchase of a first printing of the U.S. Constitution. His most serious rival in the November 2021 Sotheby’s auction was a blockchain-backed digital money collective—a “decentralized autonomous organization” known as ConstitutionDAO, which had raised tens of millions in an attempt to buy the document.

After Griffin secured the prize, he contacted members of the DAO. “We reached out about ideas like shared governance for a period of time, or allowing them to create a [Constitution] NFT for the DAO contributors,” he says. “But they couldn’t make a decision.” Instead, he will lend the document to billionaire Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, to be put on display there.

“You need hierarchy, you need leadership structure, you need clear decision making and clear lines of authority,” Griffin says. “The culture of participation trophies is not going to create the leaders we need to run our country in business or politics.”