THEY once called it Siberia.

Back then it was a small, thriving coal mining community, but today nothing remains but picturesque ruins, forgotten by most.

This is Aberdare South Colliery, originally nicknamed Siberia because 108 years ago it was way out in bush, remote from anywhere.

Or maybe it was something to do with a strange Russian connection?

Either way, the now almost hidden pit site was directly responsible for creating the nearby village of Abernethy in 1915.

There were plans to make Aberdare South Colliery, which was about eight kilometres south-east of Cessnock, the biggest coal producer in the busy mining district.

But fate intervened.

People were so optimistic that a large, solid brick hotel was built on the promise of great things ahead. That was in 1927, the same year the underground mine abruptly closed, throwing idle at least 245 mine workers and 25 pit horses.

There were plans to make Aberdare South Colliery the biggest coal producer in the busy mining district.

Today, the large and spacious two-storey former hotel is a country retreat re-fashioned as historic Abernethy House, a guest house with accommodation for 34 people.

Close by, down a rutted and sometimes flooded dirt road, is Siberia, the mine that lasted only 14 years (1913-1927) despite vast expense by its owners, Caledonian Collieries, to make it a showpiece pit.

The unlucky mine site had two owners and a railway branch line that served the single isolated colliery. The line was completed in 1918. Only a forlorn rail cutting remains today.

In the 1970s, a large amount of still serviceable rails from the branch line and colliery sidings were recovered by Coal and Allied Ltd for recycling at its various underground collieries. The rest was sold for scrap.

The abandoned mine site today, at first glance and from afar, seems almost like a piece of untouched Coalfields industrial history. But, of course, it isn't. It's been stripped apart over past decades for precious items of scrap.

These days the wilderness site is favoured by painters and bird watchers who regard it as a crucial refuge for the area's birdlife.

The old Siberia is still heavily forested as the mine didn't exist long enough early last century for all its trees to be felled for pit props. As well, the site is now adjacent to the Werakata National Park and Aberdare State Forest.

On site, it all seems awe-inspiring, except on weekends when the silence is broken by the roar of trail bikes and disturbed snakes slithering through the leaf litter.

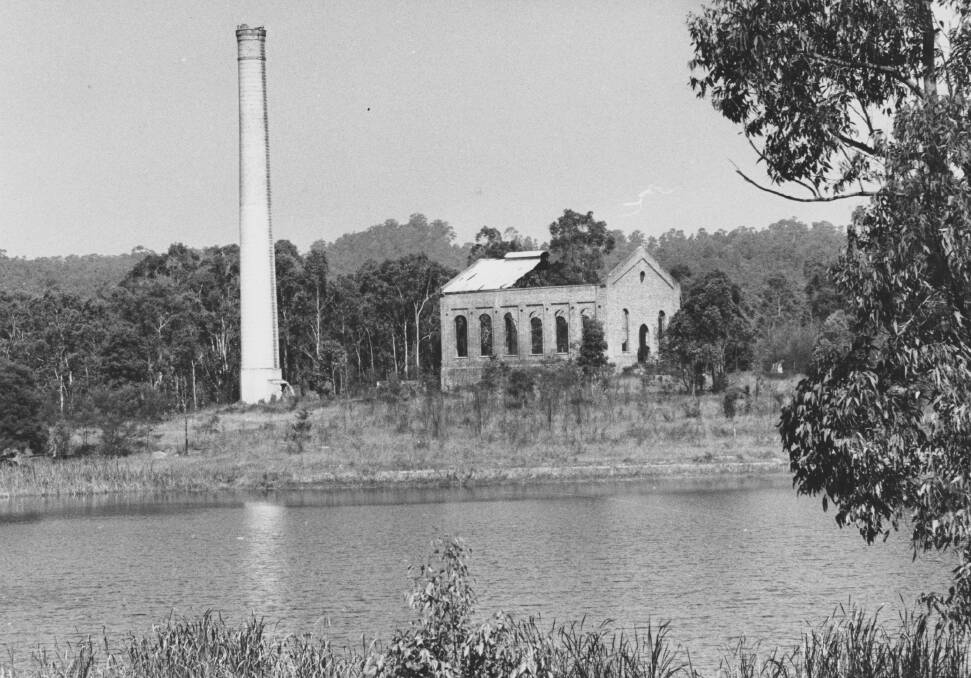

There's even a miniature lake, a huge colliery dam actually, reflecting its tranquil surroundings.

Other major talking points are a magnificent brick chimney, maybe more than 30 metres tall and a large winding house once holding the crucial, steam-driven mine engines.

This gutted, all but roofless but still impressive brick cathedral is now half hidden by new growth timber. Nearby concrete foundations of the pit top lie in bush, while an explosives store bunker, made of brick but with its heavy cast iron door long torn off, is also obscured.

My guide on a recent tour of the area was local Kevin Robinson, whose uncle Neville wrote a book in 1993 on the South Maitland 'coal rush' entitled They Called It Siberia.

"He was a schoolteacher. He spent a lot of time recording Aberdare South Colliery history before it disappeared from memory," he said.

"It's a shame the heritage of this place isn't properly preserved before it's all gone.

"My grandfather worked here as a (coal) weighman on the pit top.

"He wore a pressed white shirt to work each day. Incredible."

Kevin Robinson said part of his grandfather's "bag hut" home was still in the bush close by. Oddly enough, it had a concrete floor, so dirt could be swept out of the primitive house.

"He worked here until he was 16 years old and then went off to fight (for the British Empire) in World War 1, leaving grandma in her bag hut in the bush here before he came back in 1918," Robinson, now 71, said.

"Something should be done by authorities to save this important, surviving piece of Coalfields heritage.

"Soon it will be too late.

"I once rang a Wallsend man who had a pile of rare photos of this place. That was on a Thursday. Sadly, he died the next day, so I suppose all those historic pictures were lost.

"The Aberdare South Colliery's shaft was 1500ft deep. It was the deepest shaft of all on the South Maitland (coal) field.

"And after the pit top was dismantled, I believe the poppet head shaft wheels went to New Zealand to be used at a ski resort.

"And when the area's only pub, the Abernethy Hotel finally closed about 1932, I understand the licence went to Wallsend's Racehorse Hotel."

Robinson said the strikingly tall colliery chimney was built by bricklayers without scaffolding. It's spiralled-shaped inside to funnel the smoke out quickly.

"The tower was built from the inside straight up by Pommy bricklayers. Beautiful brickwork.

"It must be 100ft tall and when I was much younger I tried to climb up it.

"I found rung 55 up there was loose, so I didn't go up any further," he said.

The now ageing brick chimney is indeed a masterwork of industrial architecture. The circular chimney on an octagonal base may have been built by bricklayers George Cane and his son Stanley.

For the mine even had its brick kiln to supply bricks to line the coal shafts being sunk. This brickyard was run by a foreman named "Monkey" Isedale, so named because he kept a pet monkey.

"It's a wonder the chimney is still standing," Robinson said.

"It was going to be pulled down, but my father intervened."

The mine closed in 1927 due to a variety of factors. There were labour troubles, high absenteeism, the need for extra tunnel roof supports and a low coal output.

The deep mine also became the unintended sump for neighbouring collieries.

Moves were made to possibly re-open it in 1938, but the large volume of underground water made this impossible.

And the possible Russian link?

While some Russians were among the early workers living here in bag huts lit by kerosene lamps, it was an umbrella term grouping together Ukrainians and Poles as well as Scots, Irish and English employees.

Eminent Cessnock historian, the late Jack Delaney though once told me he suspected many Russians were directly sent to the region originally to build the 1905 Richmond Vale line, a unique, 26 kilometre long flood-free railway from Hexham, snaking through the Sugarloaf Range towards Pelaw Main and Richmond Main.

.png?w=600)