The elderly population in Japan is expected to peak in 2040. Can the pension, medical and nursing care systems be maintained? Particular attention is being paid recently to the "2040 problem" as related to social security. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a policy speech on Oct. 24 in which he emphasized that the government would "build a social security system for all generations," but a long-term perspective is needed when working toward systemic reform.

190 trillion yen. needed

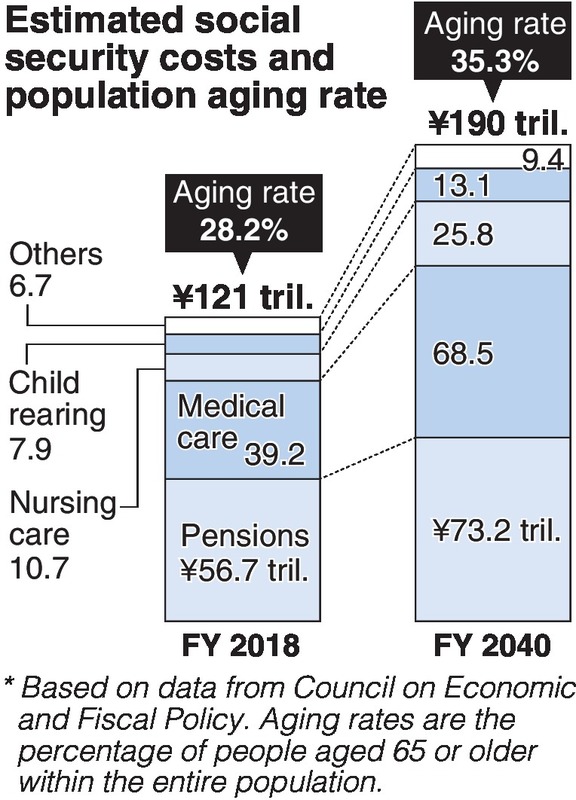

With the chronically low birthrate and aging of the population, the number of Japan's elderly aged 65 and over will increase by 10 percent from today's level, to more than 39 million in 2040. After that, the elderly population will begin to decline along with the overall population. Therefore, it is around 2040 when the burden on the pension, medical and nursing care systems is expected to be heaviest. According to a government estimate released in May of this year, the annual cost for providing social security benefits is expected to reach 190 trillion yen (about 1.7 trillion dollars) in fiscal 2040, or 1.6 times the current level.

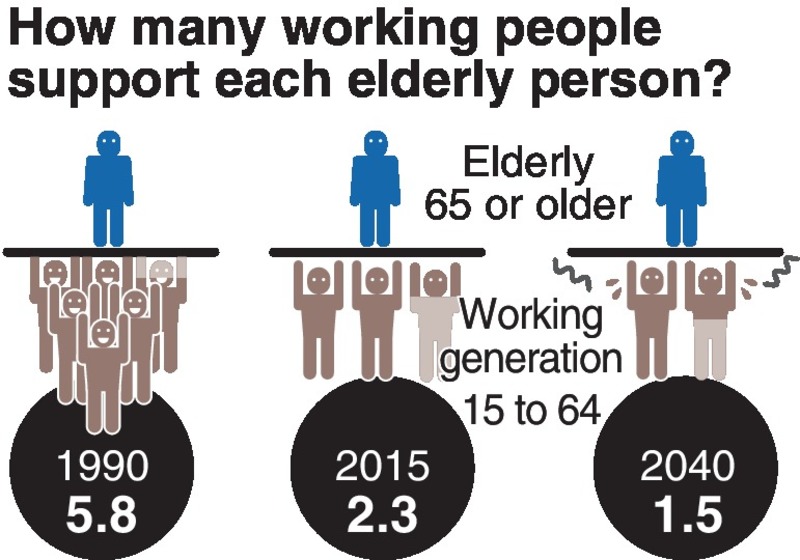

The year 2040 is attracting attention not only because its costs will be substantial, but because the size of the working generations aged 15 to 64 -- who support the social security system by paying social insurance premiums and taxes -- is expected to shrink by more than 20 percent. Currently, one elderly person is supported, on average, by 2.3 working people but by 2040, just 1.5 working people will have to support one elderly person.

Will the shrinking working generation be able to bear such an increasingly heavy burden? This is the core of the 2040 problem.

Abe called social security reform "the greatest challenge for the Abe Cabinet going forward" at a press conference on Oct. 2, the day of his new Cabinet's inauguration, after he was elected for the third consecutive time as president of the Liberal Democratic Party. He further said, "I will make reforms over the next three years to confront the national emergencies of the chronically low birthrate and aging society, and work on a social security system that all generations can feel reassured by."

Under Japan's social security system, the elderly receive generous benefits while shouldering a relatively light burden, with the working generations taking care of the rest. However, it is also true that the additional required funding is covered by government debt, passing the bill on to future generations.

The system has been described as "plunging our hands into the pockets of our grandchildren to get our pensions." It is also one factor behind Japan's serious fiscal deficit, in which the government's debt stands at more than twice the gross domestic product. It is vital that changes are made to this structure.

Concerns about the future of social security lead to decreased willingness to spend money, which is said to be a factor behind the sluggish growth in domestic consumption levels that in turn is impeding recovery from deflation. Finding a path toward a more stable system should help resolve such anxieties and should also stimulate economic recovery.

To do this, financial resources must be secured.

According to government estimates, the cost of social security benefits as a fraction of GDP will rise from its current level of 21.5 percent to 24 percent in fiscal 2040. If this increase were to be covered by consumption taxes, the existing tax rate would have to be raised by roughly five percentage points. Abe announced that the consumption tax rate will be raised by two percentage points to a level of 10 percent in October of next year, but this is based on a strategy for "integrated reform of the tax and social security systems," the target of which extends only until 2025, and there is no doubt that further tax hikes will be inevitable in preparation for 2040.

No details on resources

However, the government has not demonstrated how it will secure the future social security resources. Even in the Diet, opposition parties are focusing all their effort on pursuing the Moritomo and Kake educational institution scandals, and serious discussion of the issue has not taken place.

Abe, advocating his Abenomics economic policy package, has enjoyed some significant achievements since returning to office as prime minister in 2012. Tax revenue was increased thanks to rises in stock prices and a lower yen, and the primary budget deficit -- an index that shows how much of expenditures can be financed using taxes and other revenues without relying on debt -- has been halved.

However, with two postponements so far of a consumption tax increase, improving the budget balance has stalled since fiscal 2015, and the goal of eliminating the deficit was moved from fiscal 2020 to fiscal 2025. It is undeniably difficult to achieve fiscal reconstruction and secure financial resources based on economic growth alone, and bringing a tax increase into consideration is necessary as well.

If Abe serves as prime minister until the end of his term as party president in 2021, he will have the longest tenure in Japan's history, nearly nine consecutive years. The decision to raise the consumption tax to 10 percent was agreed upon by the Liberal Democratic Party, Komeito and the then Democratic Party of Japan in 2012 during the Yoshihiko Noda administration, and raising it beyond 10 percent would require additional political judgment. If Abe avoids such a discussion while he's in office, he could be criticized by future generations for not acting to deal with social security and tax reform in spite of having the longest term in history, and one during which the chronically low birthrate and aging population are increasingly severe issues.

The need for a national discussion on systemic reform in preparation for the year 2040 was also pointed out at the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy in May, which featured the announcement of estimates of future social security costs. It is hoped that Abe will establish a venue to examine the issues beyond the boundaries of the ruling and opposition parties, perhaps a "national social security council," and lead the discussion.

A system for all generations

The focal point of reform efforts in preparation for 2040 is the establishment of "social security for all generations." Economic Revitalization Minister Toshimitsu Motegi was appointed to the new post of minister in charge of social security reforms for all generations, a post established in Abe's new Cabinet.

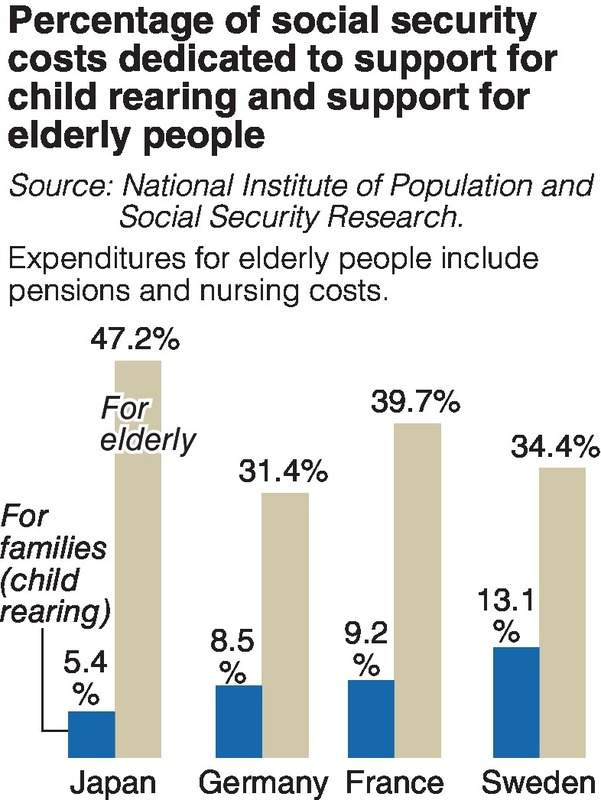

Japan's social security system includes very little in the way of childcare support, while featuring significant benefits for the elderly, such as pensions and nursing care. The concept of "social security for all generations" refers to converting the system to one that includes support for all generations, including child-rearing generations, young people and women.

The concept first appeared in the report from the panel for realizing a reassuring society, set up by the Taro Aso administration in 2009. It is based on the recognition that the decrease in Japan's birthrate accelerated after the collapse of the bubble economy, as mechanisms such as lifetime employment by companies and child rearing and nursing care by families began to become unsustainable.

The Abe administration has also displayed an attitude of commitment to the current and future working generations through projects such as the Promotion of Women's Participation and Advancement in the Workplace law, Japan's Plan for Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens,"work style reform" and free day care and kindergarten. However, none of these has corrected the chronically low birthrate, and regional population decline and labor shortages are worsening.

In Germany, progress has been made toward a system for all generations. With the aging of society, social security costs, including for labor and management, had risen to about 40 percent of income, and the Gerhard Schroeder administration, mired in low growth and high unemployment rates, began reforms in 2002. While reducing benefits for older generations, including raising the pensionable age from 65 to 67, the administration also promoted the employment of young people and women, leading to a decline in unemployment and a recovery in economic growth.

The administration of Angela Merkel, who subsequently took the reins, strengthened family policy to support child rearing, improved childcare leave benefits and systematically increased daycare facilities, creating an environment in which women can continue to work without anxiety about their children.

With the introduction of a "parental allowance" to compensate for income lost during childcare leave, the utilization rate of paternal childcare leave increased from 3 percent to 34 percent, and the total fertility rate improved from about 1.4 to 1.59 (in 2016).

"We need to create mechanisms to allow all people to become self-sufficient members of society through work, and establish a new system of safety and security," said Taro Miyamoto, a professor at Chuo University, who proposed the idea of "social security for all generations" at the panel for realizing a reassuring society.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Oct. 25, 2018)

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/