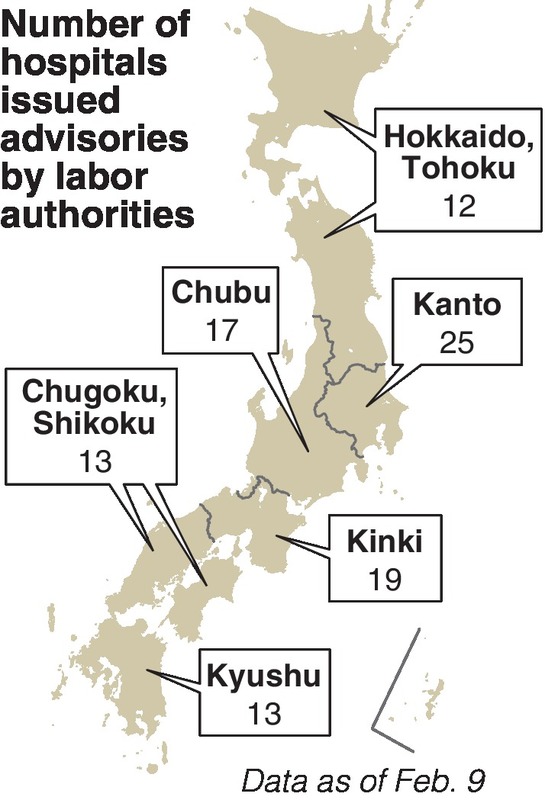

Authorities have issued advisories to 99 hospitals tasked with high-level medical care, calling on them to rectify such labor practices as illegal overtime work, it has been learned. We looked into why medical doctors work such long hours -- an issue that has been highlighted in the ongoing debate over work style reform for doctors.

Illegal overtime common

In November last year, the local labor standards inspection office in Aichi Prefecture, citing Article 36 of the Labor Standards Law regarding overtime, issued an advisory to Kasugai Municipal Hospital to correct its practice of making its staff, including doctors, work overtime, despite not having a labor-management agreement with doctors.

"We had the mistaken notion that local government employees don't need labor-management agreements," a hospital official said. "We want to conclude one soon."

Last December, Iwaki Kyoritsu Hospital -- a municipal facility in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture -- was also issued an advisory for similar issues.

"We haven't been able to conclude a [labor-management] agreement yet, due to objections such as opposition from doctors, who consider it pointless to make a pact that can't be kept," said a hospital official.

A Yomiuri Shimbun survey conducted in January of 349 hospitals nationwide showed that 71 had been issued advisories by labor authorities over illegal overtime, such as by exceeding work hours allowed in labor-management agreements.

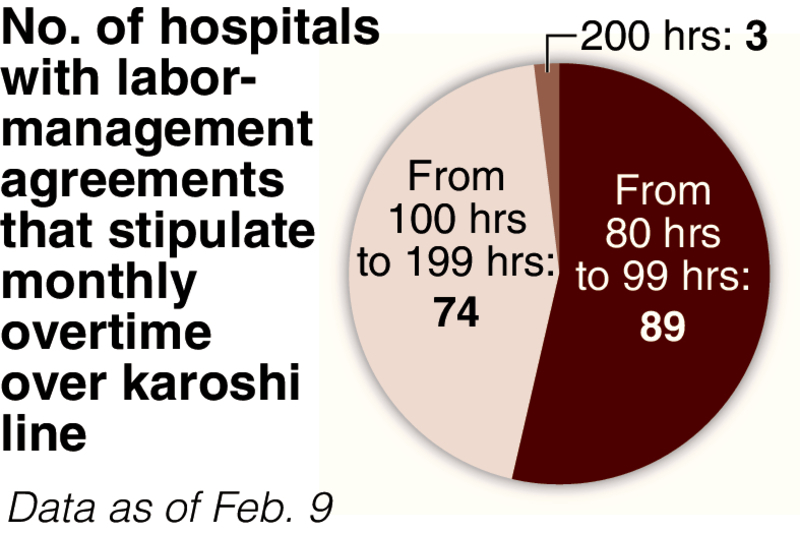

The survey also found 89 hospitals said their maximum overtime under their Article 36 agreements was 80 hours to less than 100 hours per month, while 77 hospitals said as many as 100 hours or more of overwork were allowed per month.

The Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry sets its line for karoshi, or death from overwork due to prolonged hours -- a standard for recognizing people who have suffered such ailments as a cerebral stroke as eligible for workers' compensation insurance payments -- at an average 80 hours per month lasting for two to six months.

In the survey, 18 hospitals had not concluded any labor-management agreement under Article 36.

Patients must help out

Japanese Red Cross Kitami Hospital in Kitami, Hokkaido, was also issued an advisory last year over problems such as making doctors work overtime beyond the labor-management agreement.

There are not enough doctors, but they still have a duty to respond to patients, according to the hospital.

"Emergency cases cannot be refused," a hospital representative said. "With the shortage of doctors, prolonged work is unavoidable to fulfill the mission of our emergency medical care center."

The hospital in Kitami is designated as the only emergency medical care center that accepts seriously ill patients around-the-clock from three cities, 14 towns, and one village in northeast Hokkaido.

Following the issuance of the advisory, the hospital has been working to reduce overtime such as by allocating work to staff in other job categories.

Nevertheless, a hospital official in charge of human resources said, "Given the difficulty in securing new doctors, there are limits."

Some hospitals cited a lack of doctors in specific fields as the main cause of prolonged work.

"Even if there are enough doctors, overall, we're short in the anesthesia and emergency departments," a representative at Saiseikai Utsunomiya Hospital in Utsunomiya said.

As many as 29 hospitals said in the survey that working long hours was "intended to meet patients' needs."

"Per patients' requests, doctors quite often speak to the patients and their families on weekday nights after work or on weekends," an official at a hospital in Tokyo said. "To end doctors' prolonged work, it may be vital to change patients' awareness."

A representative at Toyama University Hospital said: "Some patients request that they be seen by primary doctors, even at night, if their symptoms suddenly worsen. We want [patients] to understand the doctors on duty will attend to patients on such occasions to reduce overwork."

If doctors are exhausted and hospital operations become disrupted, ultimately it will result in disadvantages for patients. Discussions are needed that involve not only hospitals, but also patients, themselves.

Moves to curb care

Work is also underway to reform the hospital environment by placing restrictions on medical care.

Starting from June of last year, St. Luke's International Hospital in Tokyo -- which has also received an advisory from labor authorities -- decided to shrink the number of departments offering outpatient care on Saturdays to 14, leaving 20 others closed, including its neurology and dermatology departments.

The hospital is also, in principle, refusing to provide explanations to patients at night, according to a hospital official.

"To rectify the situation, [these new policies] were unavoidable," the official added.

More hospitals are also employing medical clerks, who assist doctors through such tasks as contacting patients and handling paperwork. There is already a system in place where the introduction of medical clerks means adding to medical treatment fees, but quite a few hospitals expressed their desire for the system to be improved.

"Even higher treatment fees are required to boost the number" of medical clerks, said a representative at the Hospital of Hyogo College of Medicine.

Toshihiko Hasegawa, president of the Future Health Research Institute and former professor at Nippon Medical School, said: "What's most important is making maximum use of existing human resources, such as by boosting the skills of assistants tasked with office work, and creating environments where female doctors with children can work more easily. It's also urgent to review systems that lead to doctors congregating at core hospitals."

The results of the latest survey have made it clear that reducing doctors' long working hours requires more than just efforts by hospitals. It is hoped the government will build a sustainable system through such means as using information technology to reduce the burden on doctors.

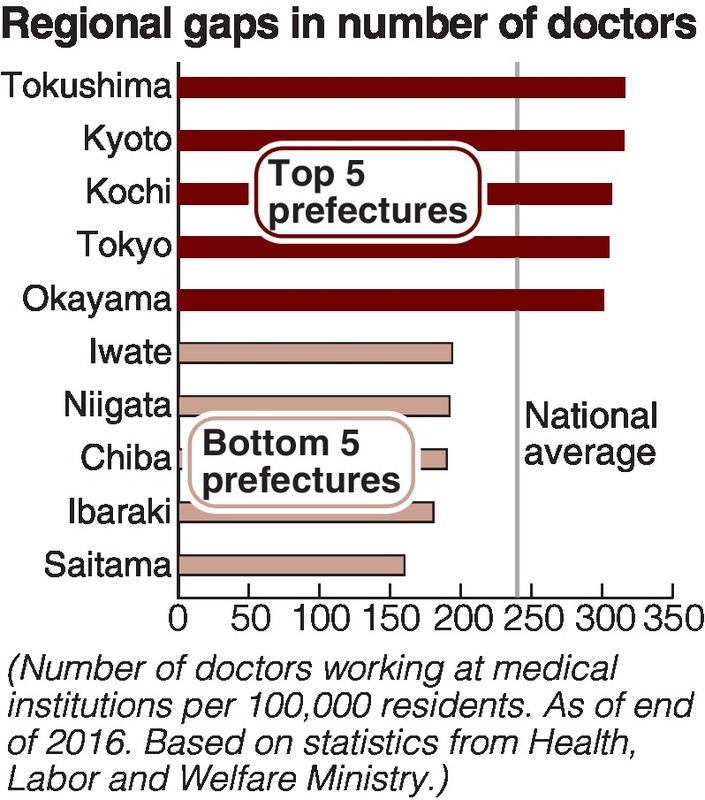

Discussion is moving forward in the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry toward work style reform for doctors and reducing the regional gap in the distribution of doctors.

As part of its work style reform policy, the government agreed to introduce caps on overtime. However, doctors were given a five-year grace period in consideration of the special characteristics of their work.

Following this decision, the ministry set up a panel of experts in August last year and discussed how overtime caps should be implemented.

On Friday, the panel compiled a draft of urgent measures to reduce doctors' work hours, deeming it important to promote voluntary measures without waiting for the restrictions to go into effect.

The draft proposes that, in principle, work such as providing explanations about examinations, admissions and instructions for taking medicine, as well as entering data for medical certificates, be delegated to other staff, including nurses, instead of doctors.

It also calls for hospitals to do things like know exactly when staff arrive and leave, even at medical institutions that do not use time cards; check labor-management agreements that set out overtime work; and promote reduced working hours for female doctors.

The panel intends to engage in further discussions on ideas such as the duty to respond to patients, with the aim of reaching a conclusion by the end of fiscal 2018.

In the latest Yomiuri Shimbun survey, many hospitals called for bridging the regional gaps concerning doctors. Tokushima Prefecture has the most doctors working at medical institutions per 100,000 people -- nearly two times the number in Saitama Prefecture, which has the least.

In December last year, another panel of experts at the ministry compiled measures to address the regional gap, including providing prefectural governments with the authority to urge medical schools at local universities to set up and increase special admission quotas for local applicants, and creating a system in which the government certifies doctors who have worked for a certain period in a region that has a doctor shortage.

Based on the opinions of the panel, the ministry plans to submit bills to revise laws such as the Medical Care Law.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/