April 10 marked the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Seto Ohashi bridge, which connects Honshu and Shikoku. With the 20th anniversary of the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge on April 5 and the Shimanami Kaido expressway celebrating its two-decade mark next year, the three-route Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Project (see below) -- called the biggest project of the 20th century -- has dramatically changed the movement of people and goods. However, its enormous debt continues to burden the Japanese public.

3 trillion yen cost

The bridge-building project, heavily sought by the region since the Meiji era (1868-1912), finally broke ground in 1969. Development of the three routes was incorporated into the New Comprehensive National Development Plan along with the construction of expressways and Shinkansen tracks, and in 1970, the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Authority was established.

In his book "Building a New Japan," former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka wrote that the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Project would cultivate an economic zone stretching from Kinki to Kyushu, and that the simultaneous construction of three bridges did not necessarily constitute an excessive investment.

The bridges between Shikoku and the opposite shore overlapped the home prefectures of not one but three former prime ministers: Takeo Miki (Tokushima Prefecture), Masayoshi Ohira (Kagawa Prefecture), and Kiichi Miyazawa (Hiroshima Prefecture). Criticism over the necessity of the three bridges was stamped out, and by the time the Shimanami Kaido opened to traffic in 1999, a total of about 3 trillion yen had been invested in the project.

Repayment plan hits roadblock

However, the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Project continues to struggle with debt, and even drivers on expressways elsewhere in Japan are affected.

Before the privatization of four public highway corporations in 2005, the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Authority held 3.8 trillion yen in debt. The debt was partly covered by the national government and then assumed by the Japan Expressway Holding and Debt Repayment Agency (JEHDRA), with the Kobe-based Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway Co. continuing to make payments. When the national and surrounding local governments halted their investments, however, the repayment plan hit a roadblock.

As a last resort, the national government in fiscal 2014 undertook an emergency relief measure to consolidate the remaining 1.4 trillion yen in debt with those of the East, Central and West Nippon Expressway Companies, with toll fees collected by the companies used to repay the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Project debt.

Expressway users fume that this violates the principle of beneficiary liability. In fiscal 2014, the three companies scaled back parts of their discount systems. A JEHDRA staff member admits that, "From the perspective of drivers in the Tokyo area and elsewhere, the arrangement must be hard to swallow."

Each company plans to fully repay its debts by 2065, at which time they will make the expressways toll-free. However, revenues from the three routes in fiscal 2016 were at 80 percent of their peak in fiscal 1999. With major repairs expected due to aging, it is unclear if the routes can be made toll-free by 2065. The Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway said that it had no choice but to increase profits in order not to become a burden on the whole country.

Yearly visitation doubles

The effects on the local region, however, have been immeasurable. Compared with 30 years ago, when ferries were the main form of transportation, the travel time for each route has fallen by around two-thirds, and the yearly nonresident population traveling between Honshu and Shikoku has doubled to about 60 million. It is no longer rare to spot cars with Shikoku license plates on the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge headed to Kobe and Osaka for weekend shopping sprees.

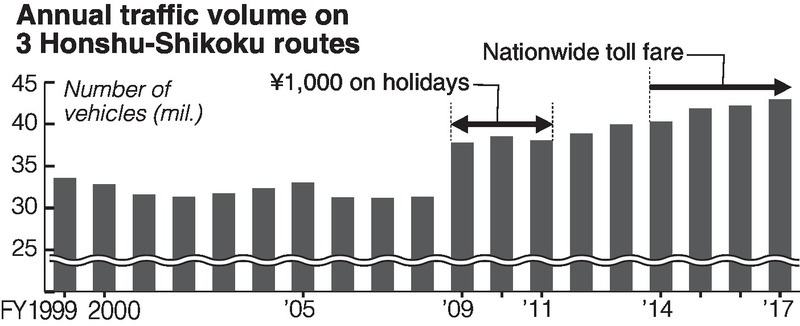

When the three routes first opened, traffic volume was initially sluggish due to one-way tolls that could cost over 6,000 yen. However, the volume increased after tolls on holidays were capped at 1,000 yen for a limited period in 2009. With the all-Japan toll system introduced together with the debt relief measures, toll fees fell to around one-third to half of their initial levels (for vehicles with electric toll collection system). Traffic volume for fiscal 2017 came in at 42.96 million vehicles, setting a new record for the sixth consecutive year.

The increase in traffic volume dovetails with continued growth in tourists to Shikoku, who numbered 13.96 million in fiscal 2016, up 14 percent from five years before. The number of foreign visitors staying overnight in 2017 rose 23 percent from the previous year. The Shimanami Kaido, which can be crossed for free on bicycle, has become a "Mecca for cyclists," with the Awajishima island, Hyogo Prefecture, and Shikoku circuits popular with cyclists.

However, a "straw effect," in which population and business have been sucked up by Honshu, has also been observed. After the Seto Ohashi bridge opened to traffic, many companies in Takamatsu integrated their bases with Okayama, Hiroshima, Kobe, and other cities on the opposite shore.

After the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge opened, commercial avenues in Tokushima city, which competed for business with the Kansai region, began to decline. The outflow of young people has exacerbated the declining birth rate and aging population, with Shikoku's current population of 3.81 million about 400,000 less than it was 30 years ago. The proportion of those aged 65 or older is 31 percent, a decade ahead of the national average.

Hajime Tozaki, a specially appointed professor of transport policy at Tokyo Metropolitan University, said of the massively debt-ridden bridge construction, "It's clear that the forecasts at the planning stages were overly optimistic."

"A higher level of discussion and explanation will be vital for future public works projects," Tozaki emphasized. "When it comes to transport infrastructure, there is significance that cannot be measured by profitability alone. Maximizing projects' potential will require efforts by local governments, such as attracting tourists."

Cutting-edge technologies

The 17 bridges straddling the Seto Inland Sea are rare in the world for their incredible scale. At 3,911 meters, the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge is the world's longest suspension bridge, and the Seto Ohashi bridge is also among the world's largest on which trains can travel. The technologies developed to protect these bridges from the Seto Inland Sea's tidal currents and salty wind have drawn attention from all over the world, and the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway is seeking new opportunities to export its technological prowess.

At the time of construction, the project's method for dropping enormous molds onto the seafloor is said to have defied common wisdom, and the design and construction technology used was exported to Turkey and elsewhere. Now the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway is working on operations and maintenance, with the aim of enabling use of the bridges for two centuries.

The surfaces of the bridges -- equivalent in size to eight Tokyo Disneylands -- were repainted with layers of a special paint that prevents rusting, and equipped with a new system that pumps dry air into the cables of the suspension bridges to prevent corrosion.

These methods have been used for the Rainbow Bridge over Tokyo Bay, as well as bridges in the United States, South Korea and other countries.

Kenji Doi, a professor of transportation and regional planning at Osaka University, has praised the bridges as "usable on a semi-permanent basis."

The Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway has dispatched engineers to lead projects in 45 countries, and continues to host survey tours from overseas. The national government, which has made export of infrastructure a pillar of its growth strategy, is planning to link up with the company starting this fiscal year, and solicit business from emerging countries as a strategic measure.

-- The Honshu Shikoku Bridge Project

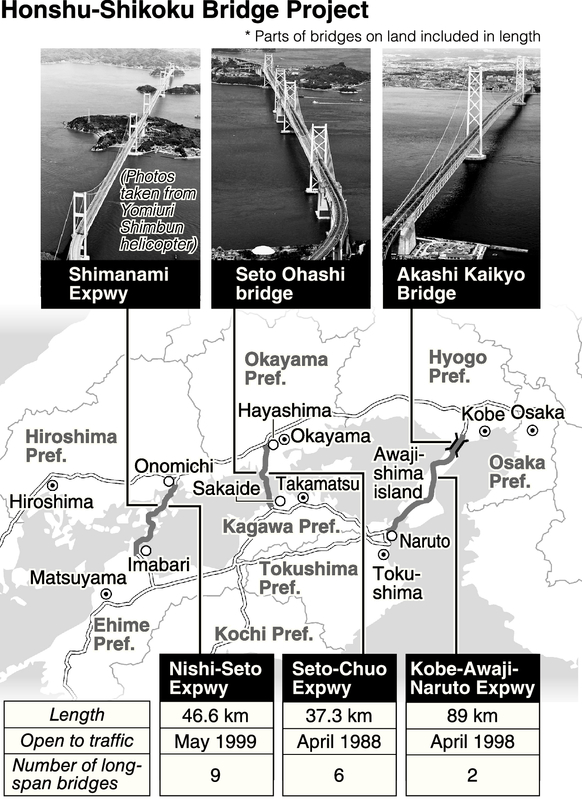

A toll-based expressway system linking Honshu and Shikoku with 17 long bridges across the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. The network consists of three routes: the Kobe-Awaji-Naruto Expressway (between Kobe and Naruto, Tokushima Prefecture), which includes the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge; the Seto-Chuo Expressway (between Hayashima, Okayama Prefecture, and Sakaide, Kagawa Prefecture), which includes the six major Seto bridges; and the Nishi-Seto Expressway (between Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, and Imabari, Ehime Prefecture), known by its nickname "Shimanami Kaido." The project cost a total of about 3 trillion yen.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, April 10, 2018)

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/