Japan's distribution system for publications, which boasts delivery of books and magazines to almost all bookstores, convenience stores and other shops throughout the nation, is facing a crisis as sales of published materials drop and nationwide labor shortages have pushed up shipping expenses. Distributors (see below) are feeling the pinch financially.

Empty spaces on trucks

In early June, employees of Oodaka Transportation Co. began transshipping works at a branch in Asaka, Saitama Prefecture, at 7 p.m. They transferred magazines from large trucks, sent from a warehouse of major distributing agency Nippon Shuppan Hanbai Inc. (Nippan), to small trucks that would then carry the magazines to convenience stores around Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefecture.

However, empty spaces were clearly visible in the truck cargo spaces. "It's true that we're facing tough times," said an Oodaka official in charge of the Kanto and Tokai regions. "The amount of magazines and comics that we transport to each convenience store has fallen, and individual trucks are visiting more stores."

In the late 1990s, when magazines were selling well, one truck would distribute magazines to 20 stores a night, but to compensate for smaller loads stemming from lower publishing sales, drivers now have to visit 50-60 stores per night. Magazines must be in the store window by the morning of their release date, so drivers travel to each store every five minutes.

Smartphones share blame

This is happening because people are moving away from buying magazines, with sales figures particularly low in convenience stores. According to the Research Institute for Publications, estimated sales for magazines in 2017 were 654.8 billion yen, down 10.8 percent from the previous year. The fall was much steeper than for book sales, which dropped 3.0 percent to 715.2 billion yen.

According to Nippan, sales of printed publications through convenience stores grew to nearly 500 billion yen from the end of the 1970s through the 1990s as the publishing market as a whole expanded. However, by 2016 this figure had shrunk to 185.9 billion yen, just 43 percent of the figure 10 years before. Because of the spread of smartphones and the rise of online bookstores, people who once bought manga magazines and information magazines are rapidly turning away from convenience stores.

In the world of distribution, the profits of magazine divisions used to cover the losses made by book divisions. Magazines were circulated in large numbers all at once, because they are published mainly weekly or monthly, while the shipping of books was inefficient due to the small numbers of many different books.

However, this traditional structure no longer works, due to sluggish magazine sales. Shipping costs are also higher, as a result of labor shortages in the transportation industry.

In its 2017 nonconsolidated settlement of accounts, Nippan saw its distribution business -- the company's main business -- record an operating loss for the first time since the company was founded in 1949, with the figure standing at 560 million yen. Tohan Corp., the nation's other major distributor, achieved sales of 427.4 billion yen, a 7.4 percent fall compared to the previous year. It saw a deficit in its distribution business for the first time in five years.

Difficult to raise prices

Along with the fall in distribution efficiency, some argue that books are too cheap. According to the Research Institute for Publications, the average price for all books for 2017 was 1,153 yen excluding tax, a marginal increase of 22 yen from 10 years ago. The average price of pocket paperbacks was 674 yen excluding tax, a 64 yen increase in the same period.

According to Nippan's public relations section, "To maintain distribution of publications, and continue selling books at stores, we need to rethink the prices."

Profits from printed publications are currently split, with 8 percent going to distributors, 23 percent to bookstores, and the remainder divided between publishers and authors. Nippan and Tohan are currently in negotiations to have publishers shoulder part of the increased shipping expenses.

However, publishers have voiced opposition to this. "Consumers aren't buying books and magazines, and the consumption tax rate will go up soon. The cost increase is just too much," a senior official of a major publisher said. It is also not desirable to simply raise the price of books, objects which form the very basis of culture.

Yashio Uemura, a professor at Senshu University who specializes in publishing, said, "The distributors of publications must find new sources of revenue and make efforts to comprehensively support bookstores."

Online retailers may be convenient, but local bookstores are places where people can happen across an unknown book and help create vibrant local communities. The convenience store environment, in which they can casually browse, also helps promote reading culture. It will soon be time to consider reforms to the distribution of publications, based on how the structure of selling printed material has changed.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, June 23, 2018)

--Distributors

These companies buy books and magazines from publishers as "book wholesalers" and sell them to retailers like bookstores and convenience stores. They perform various roles, such as transporting the printed media and collecting the money made from selling the publications from each store. Japan has many unique publishers and bookstores as a result of these distributors' efforts.

Bookshops disappearing amid financial woes

The number of bookstores across the country continues to fall.

According to the publisher Arumedia, there were 12,026 bookstores in Japan as of May this year, a 55 percent drop from the year 2000. Magazines, which regularly generate sales on the days they are released, are selling sluggishly and this is damaging retailers who are "downstream" of the distribution of printed materials.

Given that 23 percent of sales go to a bookstore, even if a bookstore sells 1 million yen worth of books in a month, it will only receive 230,000 yen itself. This is quite harsh when taking into account store rent and staffing expenses.

Publishers have independently begun to call for more of the sales to go to bookstores.

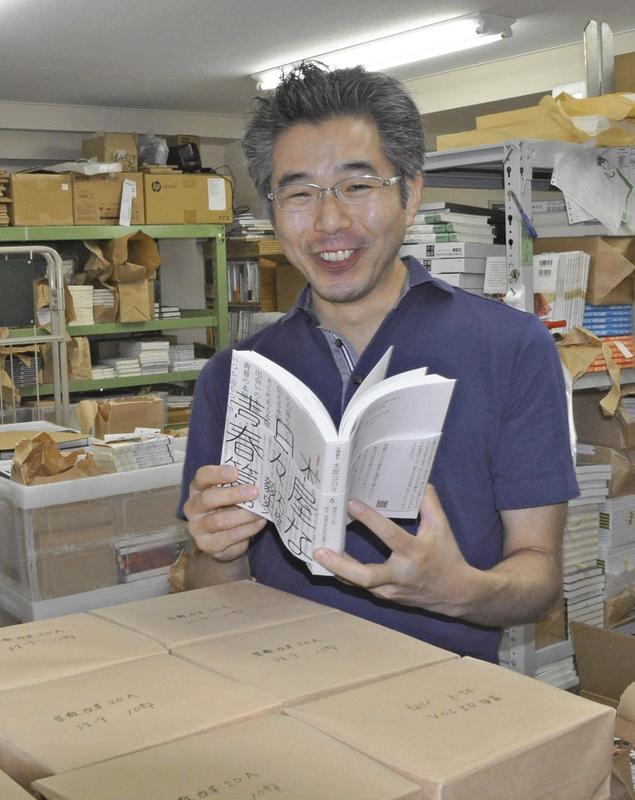

The small company Transview, which opened for business in 2001, is a strong purveyor of social science books, such as Akiko Ikeda's "Juyonsai Karano Tetsugaku" (Philosophy from the age of 14). Transview conducts direct transactions with about 2,000 bookstores across the country, deliver its books to them.

By cutting out major distributors, it can curb costs and provide bookstores with 30 percent of the profits. From 2013 they began their "transaction agent" service for books from other companies, and 70 other companies now participate. Company President Hideyuki Kudo said, "We want bookstore profits to rise and to create an environment that encourages fresh ventures into the market."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/