A wide array of countermeasures are being considered to stop piracy websites such as Mangamura, which allows users to read manga and other content for free without permission.

The proposals under review by a government panel of experts have so far included restricting advertising on these sites, making downloads from these sites illegal, promoting websites legitimately carrying manga and using web filtering software. The key focus now is whether the panel will call for legislating website blocking (see below), a measure on which opinions are divided.

"The situation has changed markedly since the government's decision in April," said Keio University Prof. Ichiya Nakamura, one of the chairs of the panel, which launched in June.

Nakamura was referring to the government's move to ask internet providers to block access to piracy websites as an emergency countermeasure, a step that resulted in three problematic sites being effectively closed down and a rebound in the sales of publishers. Discussions at additional meetings and other research also revealed that various methods aside from website blocking can be feasible.

"At the moment, I don't think the interpretation that blocking falls under the legal concept of 'averting a present danger' could stand up," Nakamura said.

However, he added: "Our next step will be to combine and share our wisdom to comprehensively compile measures. Whether website blocking is included in those measures will depend on upcoming discussions."

Efforts in other industries

Regarding possible steps to take, the precedents set by the video and music industries provide some insights.

Since 2007, YouTube has applied a copyright management system called Content ID to videos and music distributed on its website. Under this system, any content illegally uploaded to YouTube is automatically detected, and the copyright holder of that content can choose to have it deleted or to receive advertisement revenue. However, such a system has not been introduced for images.

Since 2012, the revised Copyright Law has made illegally downloading video and music content subject to criminal punishment, but the law does not apply to images. The publishing industry reportedly will start pushing for images to be covered by this legislation.

In pursuit of legal sites

Manga artist Ken Akamatsu has another idea. "To stamp out the piracy websites, we must make legal websites that are more convenient than the piracy ones," he said. Akamatsu is one of the operators of Manga Toshokan Z, a website through which users can read manga for free.

In August, Manga Toshokan Z started a trial under which it asks the public for out-of-print titles published by Tokyo-based publisher Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha, Ltd., and -- if it gets permission from the author -- carries them on the website. A portion of the profits also is returned to those who post manga content.

"We [manga artists] ourselves must rack our brains and use technology to bring our readers back," Akamatsu said.

Opinion in the expert panel remains split over website blocking as it discusses the technical aspects of this issue.

Keio University Prof. Jun Murai, another chair of the panel, said, "There are easy ways to get around website blocking, so it doesn't have much impact."

Murai has another concern, saying that "blocking involves fiddling around with the basic setup of the internet, so one mistake risks plunging the world into turmoil."

In 2008, Pakistan attempted to block domestic access to YouTube, but ended up leaving about two-thirds of the world unable to view the website.

Nobuo Kawakami, president of Kadokawa Dwango Corp., disagrees with this position. "Just because there are ways to skirt around [blocking], that's no reason" to resist introducing it, Kawakami said at a panel meeting. "There are ways to get around every crime prevention measure, so of course there will always be a degree of cat-and-mouse."

Kawakami insisted that even if blocking had only a limited effect, a combination of various measures should be adopted to protect the content's rights holders.

Some attendees pointed out that blocking likely would have some impact in repelling "casual users," such as children who were not well informed about internet technology.

There was also an opposing view, which said users who try to simply access those sites because of their limited knowledge should be dealt with by using filtering services and education targeting young people.

Blocking no easy task

Several hurdles stand in the path to legislating website blocking.

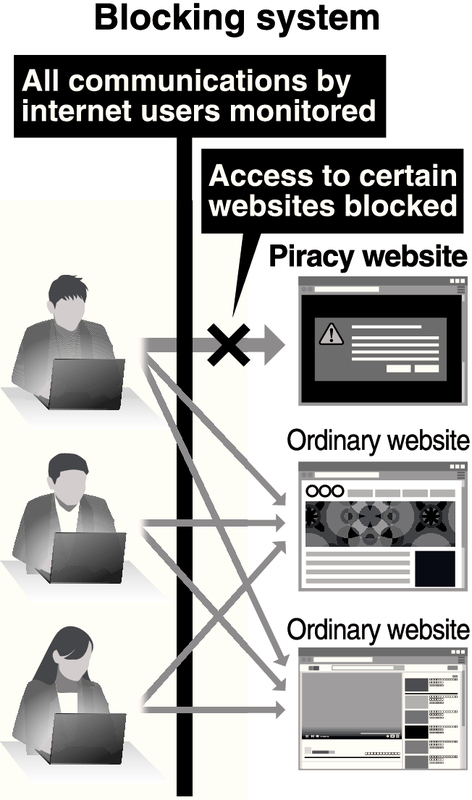

The first barrier is a constitutional issue. Blocking involves checking the communications of all internet users, finding specific websites they view and then blocking access to them. This necessitates monitoring vast volumes of communications, including those completely unrelated to viewing piracy websites.

As this would be a grave human rights violation, the constitutionality of website blocking measures should be subject to strict review.

"It has long been said that when it comes to restrictions on human rights, 'Don't use a cannon to shoot a sparrow,'" said the University of Tokyo Prof. George Shishido, a member of the panel and an expert on the Constitution. "Even if you use a cannon to shoot a small target, you might miss, and that would reduce the vicinity to smoking ruins and create tremendous damage. What's wrong with using a hunting gun?"

He continued: "The same applies to website blocking. Is there a rational method for achieving the objective? Are there other methods, such as filtering, that would be effective and not excessively infringe on people's rights? Unless these circumstances are thoroughly examined, it will be impossible to wipe away doubts that website blocking is unconstitutional."

The panel looked at other countries' legal systems that authorized blocking, but introducing them to Japan as they are will be difficult.

In Britain and Australia, for example, based on court rulings, claims can be filed for internet providers to block websites. However, these nations have legal systems in which it is also possible to file injunctions even against parties who are not directly violating the rights of others.

Attempting to allow these claims in Japan would require an overhaul of the entire legal system.

In 2015, Germany's Federal Court of Justice handed down a decision that a provider could be ordered to block websites. But Shishido said, "Communications are constitutionally protected, but the definition of the term is different in the Japanese and German top laws."

In Japan, internet use is widely protected based on the secrecy of communications. In Germany, this protection is restricted mostly to email and online chats, and browsing freely accessible websites is not covered.

The range of communications whose secrecy is protected in Germany is narrow. But that nation has a powerful guarantee of information privacy rights, leading to a recent court precedent that created the concept of the "IT basic right" with a view to tackling issues brought about by monitoring vast volumes of information.

Ryoji Mori, a lawyer and member of the panel, said: "While individual nations have the same objective of protecting the freedom of the internet, they tackle this issue with legal frameworks that differ due to their own culture and history. Japan can't simply just transplant part of another country's laws here."

South Korea's case is noteworthy. Website blocking is possible in the country under an instruction by the Korea Copyright Protection Agency, an administrative organ, or the Korea Communications Commission.

In 2013, there were 12 such cases. In 2016, this figure had jumped to 209. When combined with South Korea's response to other illegal and harmful information, 91,853 cases were examined in 2017, with 66,659 blocked and 15,499 deleted.

Nine officials are tasked with screening this mountain of requests. A North Korea-related article written by a British journalist reportedly was blocked.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Aug. 9, 2018)

-- Website blocking

The act by an internet provider of monitoring online communications and blocking the connection to certain websites users try to access. Blocking amounts to an infringement of the secrecy of communications protected by the Telecommunications Business Law. However, on April 13, the government, which had been struggling to counter rampant piracy websites, named three such websites -- including Mangamura -- and decided it would be acceptable for providers to voluntarily block access to them, based on the reasoning that it would be appropriate to block them if doing so meets the requirements of the concept of "averting a present danger" under the Penal Code.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/