Abuse by staff at welfare facilities for the intellectually disabled continues to be a problem. In a case involving the abuse of a resident at Be Bright (see below), a support facility for the intellectually disabled in Utsunomiya, the director and other staff of Zuihokai, the social welfare corporation that operates the facility, were charged with violating the law on general support for persons with disabilities. Insular facility operations and a dearth of staff training were found to be problems. Many facilities continue to struggle with transparency and how to improve the quality of staff.

Managing through force

According to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, there were 2,520 cases of abuse of disabled persons in fiscal 2016. Of these, 401 were committed by facility staff, an all-time high. Nearly 70 percent of the victims had intellectual disabilities. Staff may become accustomed to raising their hand at the intellectually disabled, with whom they work with night and day and struggle to communicate. Such patterns arise.

At her trial, a 25-year-old former Be Bright employee convicted of inflicting bodily injury said senior staff told her to "[hit] just hard enough not to hurt." It was noted at her sentencing that, "At facilities unseen from the outside, violence tends to escalate with the simple idea that it's easier to manage through force." The fact that "staff did not receive training on the special qualities of disabilities" was also acknowledged.

According to a source with knowledge of the investigation, Be Bright denied family members from visiting the assault victim for approximately eight months. Tochigi prefectural and Utsunomiya city governments could not grasp actual facility conditions as they merely scanned financial statements and other files submitted by Zuihokai.

Dysfunctional oversight

In a partial amendment to the Social Welfare Law aimed at improving transparency in welfare facility operations, social welfare corporations were required to establish "watchdog" councils beginning in April 2017. However, they're far from fully functional.

Council members include lawyers, parents of residents and executives of other corporations, and board meetings must be called twice a year. The councils have the power to nominate and dismiss directors and can request investigations and reports into incidents or accidents when they occur in welfare facilities. Zuihokai also had a council, but it did not have the eight members required by law. In an interview, one of the members said, "The chairman is an acquaintance and I'm just lending a name [to him]."

Aiseikai, which runs support facilities and group homes for the intellectually disabled in Nakano Ward, Tokyo, has maintained a council as a consultative body since before the law was amended. Its members include lawyers, professors, clinical psychologists and experts on sexual minorities and the socially disconnected. Council meetings are called four times a year, and discussions held with the board of directors.

After a case involving staff abuse came to light in 1999, Aiseikai reshuffled directors and continuously made organizational reforms. Yasunobu Katayama, one of its directors, said of the reasoning behind the system, "The decay of the board provides fertile grounds for abuse."

In its present form, however, the law permits boards of directors to recommend council members. "In the end, the boards can do as they please," Katayama said. "There are probably a lot of organizations like that."

More staff, less abuse

Building relationships of trust with the disabled, with whom it is often difficult to communicate, requires training of nursing staff and enhancing the quality of care through staff discussions. An initiative by the city government of Hachioji, Tokyo, for an at-home care service, in which many employees of the service help each other boost their skills, offers insight into how this can be accomplished.

The service initially only treated those with severe physical disabilities. After the general support for persons with disabilities law was implemented in 2013, it expanded services to those with mental health problems and intellectual disabilities. Last summer, it began helping a man in his 20s with severe intellectual and behavioral disorders. The staff of 10-plus work from four entities in the city and split day and night shifts, and are testing a 24-hour care service to help him live independently.

Though staff members' strengths vary, veterans teach newcomers how to care for the man, among other skills, through written memorandums and quarterly meetings. Through frequent discussions and exchanges of information, the employees devise treatments suitable for him. The participation of many staff members also helps prevent verbal and other forms of abuse. Jun Inoue, a 47-year-old veteran staff member, said, "Rather than have people adapt to the style of one facility, it's more efficient to consider customized support methods."

The Human Care Association mediates between the family of the man and the municipal government. The Hachioji-based organization works to support the independence of disabled persons. Its president, Shoji Nakanishi, said, "[The individualized care approach] is still in the trial stage, but we hope to develop know-how and spread it nationwide."

--The Be Bright resident abuse case

In April 2017, two staff members kicked and assaulted a 28-year-old resident, causing severe injuries that took six months to heal. Both were charged with inflicting bodily injury, found guilty and handed suspended sentences in December the same year. Two retired Tochigi prefectural police officers, who worked for the management organization and oversaw an internal investigation of the incident, received summary orders in October 2017 to pay fines of 300,000 yen for destroying evidence. Moreover, on Feb. 1, three Zuihokai executives were charged with violating the law on general support for persons with disabilities for submitting a fraudulent report (dated Aug. 30, 2017) to the Utsunomiya city government which stated, "There is no abuse."

Work pressures, low pay reasons for frustration

"The burden on staff is especially heavy when handling those with intellectual and behavioral disorders, as they can hurt themselves and others," says Naoki Sone, associate professor of welfare for disabled persons at the Japan College of Social Work. "Staff unfamiliar with appropriate support methods can only control them through physical force. The quality of support and staff abilities should be improved through training courses and other methods." On the other hand, some believe that low pay and staff shortages are the underlying causes of rampant abuse by staff.

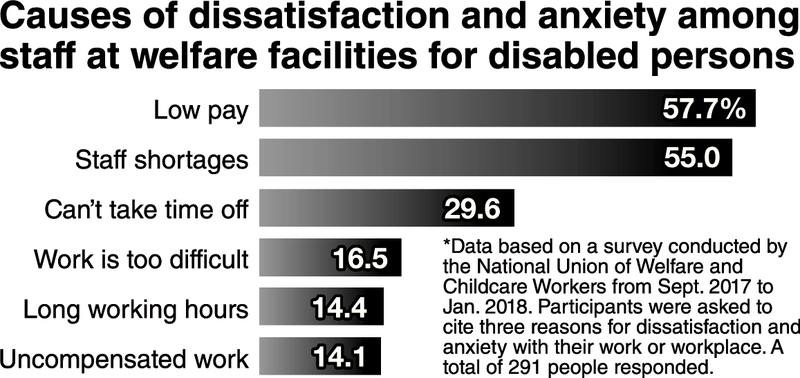

According to a Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry survey, nursing care staff at welfare facilities earn about 220,000 yen per month. This is about 90,000 yen lower than the average for all industries. In a survey conducted from September 2017 to January 2018 by the National Union of Welfare and Childcare Workers, which represents nursery teachers, nursing care staff and other professionals, over half of respondents cited "low pay" and "staff shortages" as reasons for dissatisfaction and anxiety. Notable comments include, "Although we're responsible for people's lives, that's not reflected in our salaries" and "The staff is too shorthanded to provide attentive support."

Some facilities now include anger management in their training courses. About 30 employees attended the first anger management class held in the summer of 2017 at Mizuki, a support facility for the disabled in Fuchu, Tokyo. "The staff have developed an awareness of when they become angry," the facility director emphasized.

Shunsuke Ando, president of the Japan Anger Management Association, added: "It is said that anger settles six seconds after its peak. It's effective to share in the workplace methods for letting [anger] pass, such as taking deep breaths or temporarily leaving the room."

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Feb. 16, 2018)

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/