Fabrications in a research paper were revealed in January at Kyoto University's Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA), known as the central hub for induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell research. CiRA is one of Japan's leading research institutes, respected not only for its exceptional research achievements but also for the strictness of its efforts to prevent research misconduct, a status that has highlighted once again the difficulty of preventing fraud.

"We thought we could prevent misconduct before it happened. It's been proven that this way of thinking was too optimistic," CiRA director Shinya Yamanaka said with a pained expression after bowing deeply at a press conference at Kyoto University on Jan. 22.

The fraudulent paper (see below) was published in a U.S. scientific journal last February by CiRA program-specific research center assistant professor Kohei Yamamizu, 36, and others. An internal report was later given to CiRA, and an investigation found that there had been fabrications and falsifications, including rewriting data for 11 out of the 12 graphs that were published.

Yamamizu is said to have told investigators, "I wanted to improve the appearance of the paper."

However, there was a high degree of wrongdoing, including manipulation of nearly all of the graphs. Osaka City University Prof. Ayumi Shintani, who specializes in medical statistics, flatly rejected Yamamizu's explanation: "The graphs were created from impossible data, which goes beyond the level of improving the appearance. Any researcher who understands statistics would have noticed their unnaturalness immediately."

Submission of notes

CiRA was founded in the spring of 2010 with strong backing from the government, aiming to create domestically developed applications for iPS cells. Vowing to live up to public expectations, Yamanaka took the lead and enacted rigorous fraud-prevention measures. The rules include requiring all researchers to submit their experimental notes once every three months, and banning writing notes in pencil, as they could be erased and rewritten. When a paper is set to be published, researchers are also required to submit the original pre-analysis data. A counseling office where fraud claims can be lodged was also established at the center.

Even though Yamamizu's 86 percent submission rate of his notes was higher than the about 70 percent that was the center's average, CiRA did not perform detailed checks. At the press conference, Yamanaka had no choice but to acknowledge, "Our countermeasures had been reduced to a mere name."

However, the misconduct was exposed due to the internal report to the counseling office and the preservation of the original data. "It would be fair to say that it was discovered because they had a proper system in place. There is also the concern that it might have been overlooked had it happened at another research institute. The extent of misconduct is profound," points out Kindai University lecturer Eisuke Enoki, who is well-versed in research misconduct.

Preventative measures

Research misconduct is particularly conspicuous in life science fields. This is believed to stem from the fact that results can vary depending on factors such as the skill of the experimenter and the condition of the cells used, making it difficult to recognize fraud, even when reproducibility is lacking.

The RIKEN research institute, which was rocked by a fraudulent research paper on STAP cells in 2014, is going all-out on measures to prevent a recurrence. It has appointed 30 new research ethics educators who oversee multiple laboratories, and it keeps a watchful eye out for misconduct laboratory-wide.

"We're making steady efforts to ensure that research misconduct never happens again," a related RIKEN official said with a determined expression.

Since 2014, the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, where research misconduct took place in connection with the hypertension drug Diovan, has established a system in which statistics experts perform data analysis and create graphs for clinical studies, and verify whether the paper was published correctly. The University of Tokyo's Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences, where fraud was discovered in 2014 and again last year, is also considering establishing a new education course on statistical processing.

CiRA will also increase its submission rate for experimental notes to 100 percent going forward, as well as strengthen countermeasures, such as thorough reviews of the data backing up graphs by the staff in charge of intellectual property. All eyes will be on CiRA's efforts to make adjustments to reclaim what Yamanaka called "credibility lost overnight."

--Paper recognized as fraudulent

Researchers purported to have used human iPS cells to reproduce the action of the "blood-brain barrier," which prevents foreign substances in the bloodstream from diffusing through cerebral blood vessels and entering the brain. This was considered beneficial to research on delivering drugs to the brain, and it was believed it would lead to the development of therapeutic drugs for conditions like dementia. When Kyoto University remade the graphs using original data, it was concluded that the genes usually operating in cerebral blood vessels were not activated, and the blood-brain barrier was not replicated.

(From the Yomiuri Shimbun, Feb. 2, 2018)

Pressure on research

Yamamizu earned his doctorate from the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine in 2010. After serving as a researcher at the U.S. National Institute of Health, he was hired in November 2014 by Kyoto University's CiRA for a limited term. His term of service is set to end at the end of this March.

Of the center's about 400 researchers, 90 percent are employed on the same limited basis as Yamamizu of no more than five years in principle. If they can produce achievements, their term of service is extended. "Everyone feels the pressure," said Yamanaka. Many people have said this kind of research environment leads to desperation and can potentially be a factor that gives rise to impropriety.

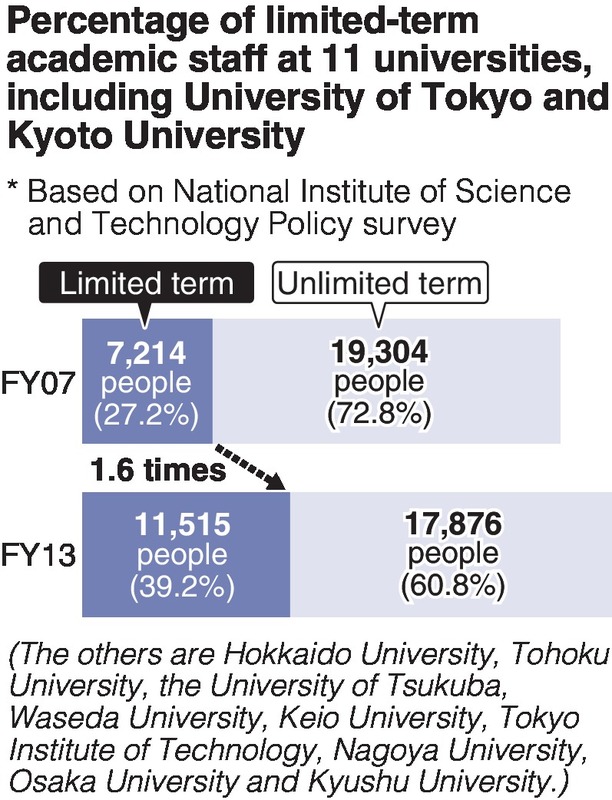

The number of academic staff at universities and researchers with limited terms is growing. According to a National Institute of Science and Technology Policy survey, at 11 top universities, including the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University, the number of limited-term academic staff grew from slightly under 30 percent of the overall number in fiscal 2007 to nearly 40 percent in fiscal 2013.

Furthermore, 60 percent of the 2,900 who completed doctorate programs in fiscal 2012 and were working at universities and other institutions 18 months later were on limited terms.

Behind this is the government's commencement of a policy in the 1990s -- aimed at bolstering the nation's scientific and technological strength -- to increase the number of doctorate recipients, hire researchers on limited terms, and make them compete with each other.

A male researcher in his early 40s who works on a limited term at a government research institute said: "This is a world in which you're evaluated based on your ability, so it can't be helped. But when the end of your term gets close, you're too preoccupied with job hunting. You can't concentrate your energy on research."

Efforts to remedy the lack of job security for researchers have begun. While RIKEN has roughly 2,800 limited-term researchers, accounting for 90 percent of the total, they are currently considering a plan to begin next fiscal year that will reduce this to 60 percent over seven years.

"We want to move away from the short-term results-oriented approach, and increase secure employment," a RIKEN official said.

The government serves as a bridge to stable positions for outstanding young researchers. It subsidizes research costs, among other measures, for universities and companies that take them in, and promotes job placement for researchers.

Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences lecturer Yo Shinoda, who is knowledgeable on employment issues for young researchers, said: "It's also important for businesses to utilize talented people with doctorates. Posts at universities and other institutions are limited, so researchers ought to be open to working for a company as well."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/