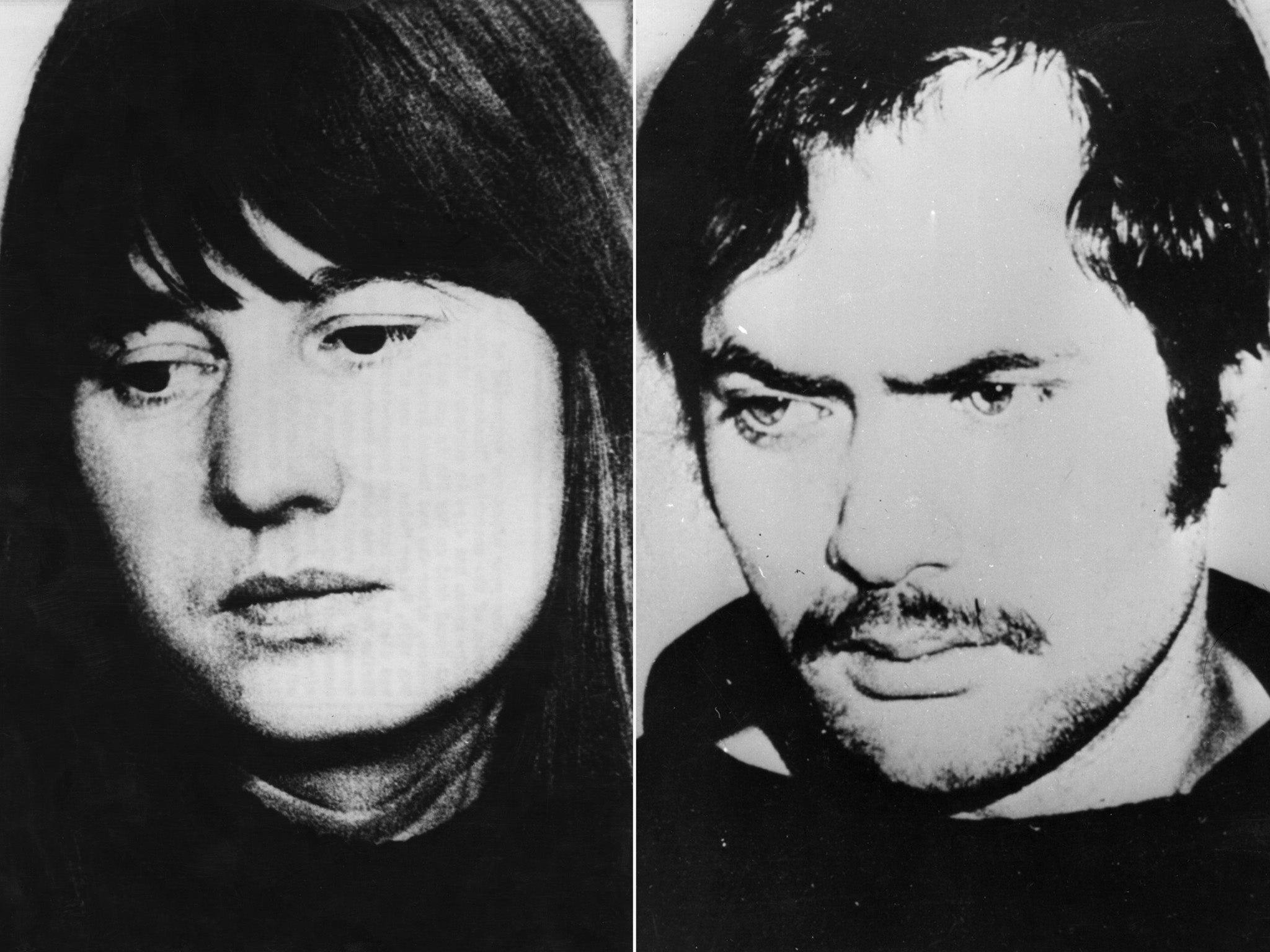

ifty years ago a 35-year-old journalist from Oldenburg in Saxony named Ulrike Meinhof authored a manifesto setting out the political aims and ideology of a group she had helped to establish. It demanded a left-wing revolution to overthrow the capitalist West German state and advocated a campaign of violence to achieve it.

The cover of the manifesto, entitled The Concept of the Urban Guerrilla, carried a red star alongside an image of a Heckler and Koch MP5 submachine gun. The logo had been commissioned by another member of Meinhof’s cohort, a 36-year-old man called Andreas Baader from Munich. Their organisation would become the Red Army Faction, better known – especially in the English-speaking world – as the Baader-Meinhof Gang. And they would go on to assassinate more than 30 people alongside a campaign of bombing, kidnapping and violent robbery.

The group rarely called itself Baader-Meinhof, preferring the German name Rote Armee Fraktion or RAF. They were a Fraktion, or fraction, because true to their Marxist-Leninist dogma they had no leaders as such, they were a single part of a greater revolutionary worldwide movement. However, the acronym RAF was always going to be confusing for English-speaking audiences and “fraction” rather than faction sounded erroneous, so Baader-Meinhof Gang (BMG) it was.