Sandra Cisneros is an American national treasure but lives in Mexico. Her debut novel caught on so slowly that this daughter of immigrants didn’t quit her day job for 15 years.

A modern classic, The House on Mango Street has sold more than six million copies and is translated into 25 languages. It’s required reading at schools across the United States. This year, the NEA selected the book as one of five Big Reads, alongside works by Toni Morrison and Jack London.

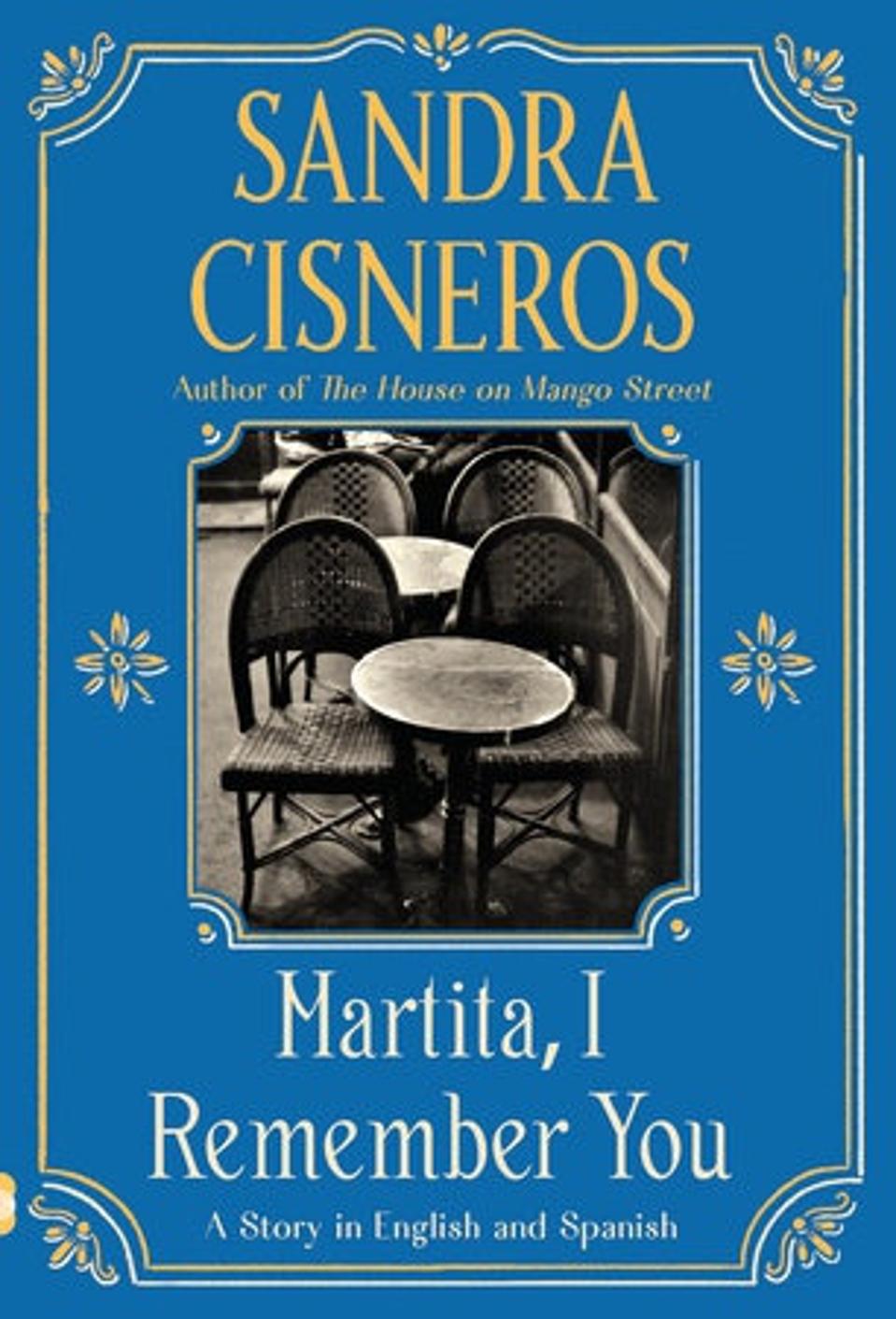

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo (Vintage, September 2021) is Cisneros’ first published fiction in almost a decade. The story involves Corina, a young artist pursuing literary dreams in Paris, and her intense friendships with fellow ex-pats Martita and Paola. Over time, the three women drift apart—until years later a letter evokes powerful memories of their time together in the City of Lights. The bilingual paperback is written in English on one side. Flip it to read a Spanish translation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The House on Mango Street, one of your most famous works, and your collection of essays, A House of My Own, are both about home. What inspires the topic?

I lived with nine people for the first part of my life, a very noisy house. They filled the silence with television, radio, music, chattering, yowling and couldn't understand why anyone wants to be quiet.

What's your house like now?

Very quiet. If the laptops on, I'm paying attention. There's no background music, except the birds, the wind, the weather—and maybe my Chihuahuas yapping. I listen to a soundtrack in my head: dialogue, conversations, events in the past, sentences I'm putting together, or the sounds of the trees and birds.

What inspired Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo?

The pandemic. I finished Martita, a 30-year venture. Yesterday, I finished 30 years of poetry. I’m not getting on planes. The more times I’m still, the more work I get done.

The book is told through letters. Was it inspired by real events?

I met these women in real life but created a composite. There were more than two and they were speaking different languages—Italian, Spanish, Serbo-Croatian, textbook English. I tried to put all of that together in these two characters. There is a real Martita out there who sparked this story, but I lost touch with her. I hope this story will be my letter to her and we find her. I can't remember her last name.

Why did you use the dual-language format, with Spanish and English in the same book?

No, no, no, Martita in my memory speaks Spanish. When I'm writing it in English, I'm trying to make her sound like she's making Spanish. The title was always Martita, te recuerdo. Only recently did we add Martita, I Remember You.

You worked with your longtime friend Liliana Valenzuela on the Spanish translation.

I was just the critic on her shoulder, going through all the pages of the book and trying to get it just right. It was the first time I've put my hands in the bowl of dough and worked with the cook. In the past, I hadn't much. But this time, I was in the kitchen and getting my hands messy. It was fun.

Why were you hesitant before?

My Spanish is a daughter’s Spanish. It's very limited. I had an interview yesterday with [Univision news anchor] Jorge Ramos and couldn't find the words for what I wanted to say. It's okay if I'm chattering but for heavy duty questions, I don't have the vocabulary. I couldn't write this myself in Spanish.

However, some new poems in the new book were. I translated them to English. Whenever I write though, I have Liliana proofread. My Spanish is pocha [Americanized]. I’m a girl from the other side of the border, troche moche [helter-skelter], you know.

With your art, do you feel like you're ever putting too much of yourself into the public view?

No, I don't. That's the only way I know how to write. If I don't forfeit some private secret or some private thought, the writing won't take off. Even if I'm writing in someone else's voice, they have to explore things that I'm afraid to talk about. That's how I know I’m getting into the good stuff.

It's like when you go into water. It's not enough to put your head under and blow bubbles. You’ve got to go to the bottom of the pool. Society has caused us—as women, as daughters, as lovers—to feel as if we’re not allowed to think, let alone talk about certain subjects. I want to uncensor myself.

You’ve said, “I write because the world we live in is a house on fire, and the people we love are burning.” What did you mean?

Each of us has some wound because of our own life experiences, which we see with our own special glasses. We know that street. We know that address. We know that community—and we know that they're in a dire situation. And we're the ones that are being called upon to save them.

It can seem overwhelming, but this is a time when we need to do something about it. Sometimes people say, “Oh, I can't do anything. I'm just a drop in the bucket.” I'm not asking you to fill up the bucket—just take care of your drop. If everybody took care of their drop, think of what change we can make.

Listen to The Revolución Podcast episode featuring Sandra Cisneros with co-hosts Linda Lane Gonzalez, Kathryn Garcia Castro, and Court Stroud on Apple Podcasts, iHeartMedia, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Podcasts, Deezer or by clicking here.