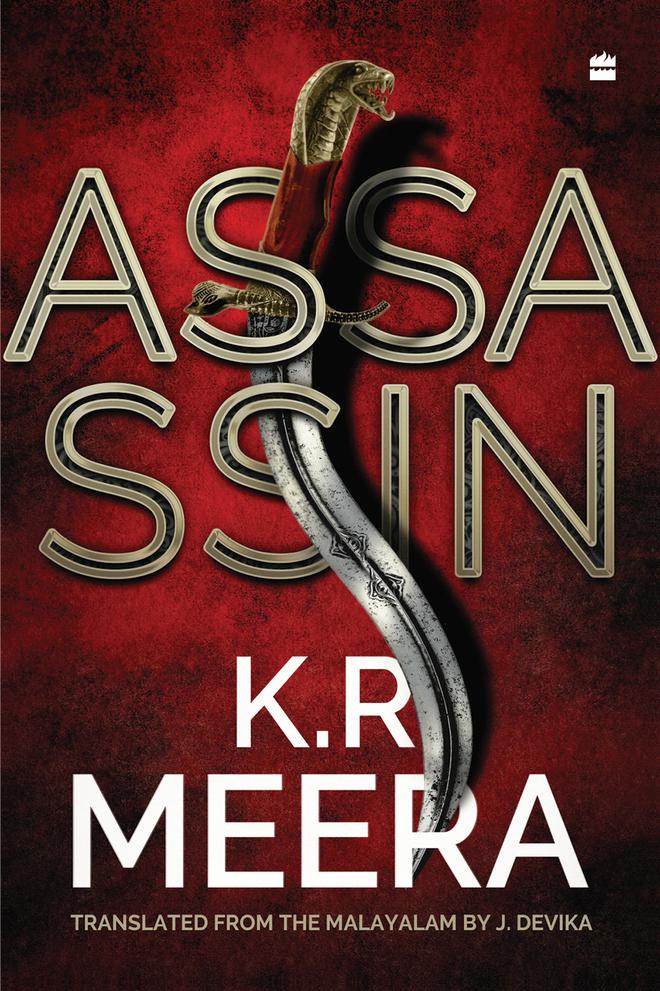

K.R. Meera’s new book, Assassin, releases this week, and it won’t be an exaggeration to call it her magnum opus. Originally titled Ghathakan and translated from Malayalam by J. Devika, this is her most ambitious novel to date, and also her most personal. In this thriller set against real-life events, the protagonist, Satyapriya, turns detective as she races against time to find her assassin, while the author, lightly and deftly, slips in the hard, unforgiving truths that lie between the folds of fiction. Edited excerpts from an interview:

The canvas of ‘Assassin’ is breathtaking — a vast playing field, populated by complex characters. What was the process of its creation like?

The seed of this book was actually planted in 2017, after Gauri Lankesh’s murder. One year later, I sat down to write, and it’s interesting that that day, I started three chapters of three different novels. All three were from my life, from varying time spans — like three kinds of flowers in the same garden.

After a few days of toying with these chapters, I centred on Assassin, and it started growing — sprouting leaves and tendrils.

Listen | An extract from K.R. Meera’s new novel ‘Assassin’

In one of your earlier interviews, you spoke about the three elements to every story — the story, the political message and the universal message. What would these be in ‘Assassin’?

That’s for the reader to find out, but what I can say is that, by telling the story of a woman of my generation, someone who was born in the 70s, one can effectively comprehend or summarise the history of our nation. So, of course, there was a personal level, then there is that political layer, and again there is a kind of universal layer, which every writer aspires to.

After ‘Hangwoman’, you talked about going through a period of depression due to the dark subject you’d dealt with in the book. Now, with ‘Assassin’, you have revisited and relived so much of your life. How has the process affected you?

Surprisingly, in a way, it was easier to write this book. It is based mostly on my first-hand experiences, and whatever I have heard and seen. So, it was easy to assemble together all these bits of truth to create a bigger truth.

But the process itself was painful — a hundred times worse than what I endured after Hangwoman. The post-Hangwoman depression was nothing compared to the post-Assassin panic attacks.

Reliving some of the experiences I wanted to forget, was pure suffering. It was like cutting myself open and taking out the hidden story.

During interactions, K.R. Meera’s readers are often curious about her writing style and how her work is affected by the current political situation. There are questions on the freedom the lens of fiction can bring to work inspired by everyday reality. As part of the promotion around ‘Assassin’, Meera is expected to visit bookstores in Delhi, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode this month.

What is the force that drives your writing?

In the beginning, I wanted to tell stories that would interest the world. I wanted to convey some message to the world. Now, especially after Hangwoman, the thrill of writing is to find more about myself. It’s like digging many layers of myself, or unfolding myself. With every book, I lose an outer self of mine. Of course, my character and mental make-up have changed. I’ve become more neurotic. All the sane elements in me are being kind of written away. But then, while writing leaves me wounded, injured, in pain; the therapy is also to write more. This is a vicious cycle. I don’t think I can get out of that.

The women who populate your books are flesh and blood creatures — complex and full of contradictions…

As an author, I always want to write or tell stories that are not told by others. This is a big challenge, because everybody is writing stories, and there are so many stories being told in English, in Malayalam, in all the other languages. The greatest challenge any writer faces is to find a story that has not been told.

And I think there is only one solution for this. You can look at the lives of women around you and create new stories. Maybe that’s because women’s stories are not written as much as they need to be.

The book is a wonderful blend of detective fiction and black humour. Why choose these stylistic elements?

In continuation to the last question, it’s not enough to find an untold story. You have to find unusual characters and unfamiliar truths in the story. I am always playing with different kinds of moulds for my stories, and I thought this particular mould was suitable to tell the story of Assassin.

Also, I began writing Assassin in 2018. Those days, there were not many women writing thrillers in Malayalam. So I thought, okay, I shall try that too.

A big aspect of the story in ‘Assassin’ is the importance of memory — the power it holds over us, and the way it can transform or transport us.

I think I am obsessed with the idea of memory. My first book, a short story collection, is called Ormayude Njarambu (The Vein of Memory). So, I have this idea that this labyrinth of memories — all these stories and memories and dreams and daydreams mixing up — is always within us. Without that, I don’t think I can write.

A motif that appears and reappears throughout the story is the face of Mahatma Gandhi. Could you talk about the importance of this?

I keep going back to Gandhi, and did so especially during the writing of this book. When I look around and try to understand the political changes happening around me, I see a surge of violence, or of using violence as a tool. Some force is compelling us to normalise violence in our life. And I think any Indian citizen will have to go back to Gandhi, not because he’s the rashtrapita, because the idea of non-violence is very important to the world.

And, as I said, every observation in this book is actually my own truth. When you think about truths, you think about Gandhi. When you think about non-violence, you think about Gandhi. When you think about patriarchy, you think about Gandhi.

The book is rich with details. Nothing escapes notice — even the dialogues have this air of being recorded in real time.

I was trying to capture the life of a woman in that time span, so it was very important to document the kind of clothes, food, types of houses, everything. You can see that the whole book is like a documentation of the lives of the women of our generation. That’s why even the conversations are documented in that way. It’s kind of like creating a record for the readers of the next generation, in terms of caste, in terms of money. Of course, as middle-class women, our lives are mostly manipulated or kind of moulded by the concept of wealth. Our concept of well-being is completely linked to the money we save.

All writing has rhythm, a style that is the author’s own. I’m curious about how you think the rhythm in your work translates to English?

I think it works very well when Devika translates it, because somehow I always think she can understand me well, because we share the same realm of imagination and even the personal and political. Of course, English is a different language, it has a different grammar, and a different cultural context. It’s not easy for a translator to capture the meanings of certain words and bring them out in English. But then I always expect a reader to find them out and decipher the exact thing I meant.

swati.daftuar@thehindu.co.in