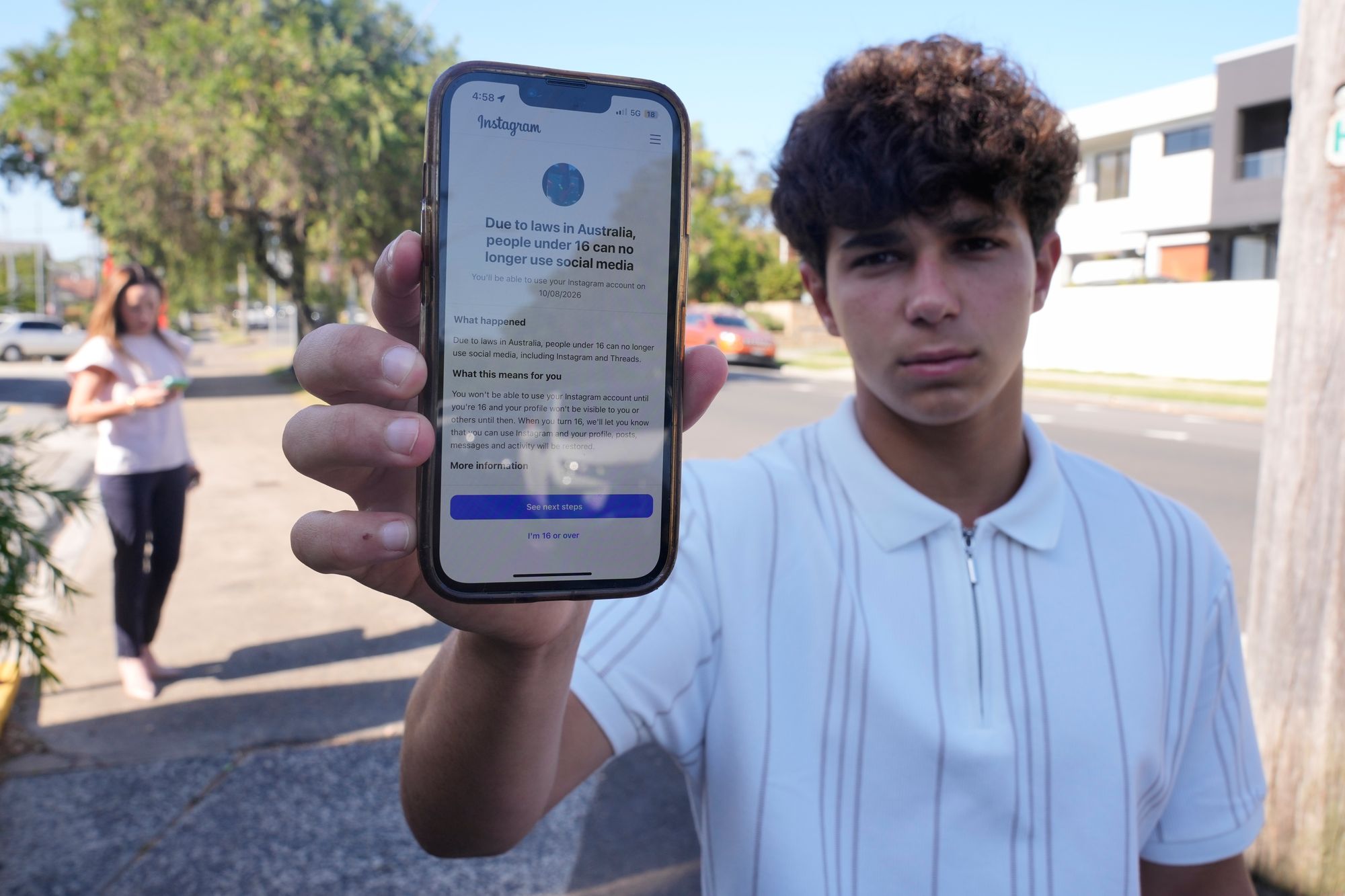

Australia started enforcing a world-first prohibition on social media for children under 16 on Wednesday, compelling platforms to lock out young users or risk heavy financial penalties.

The measure, which took effect at midnight, requires 10 of the largest social networks, including TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, and X/Twitter, to keep under-16s away or face fines of up to A$49.5m (£26.5m), making it one of the world’s toughest digital restrictions.

The prime minister hailed the start of the ban as “a proud day”, insisting that Australia had shown countries everywhere that online harms did not need to be accepted as an inevitable feature of modern childhood.

“This will make an enormous difference,” Anthony Albanese claimed. “It’s one of the biggest social and cultural changes that our nation has faced. It’s a profound reform which will continue to reverberate around the world.”

But in the hours before the law came into force, many young users posted mournful public farewells. “No more social media,” one teenager said on TikTok, “no more contact with the rest of the world.”

Other users added hashtags such as “#seeyouwhenim16”.

The ban is expected to affect over a million accounts.

The prime minister posted a video message encouraging children to use the summer break from later this month to “start a new sport, new instrument, or read that book that has been sitting there for some time on your shelf”.

Though the prohibition has been welcomed by some parents’ groups and child safety advocates, major technology companies and civil liberties organisations have warned that it could compromise privacy, encourage children to lie about their age and push young people onto riskier platforms.

The law arrived after a year of political debate in Australia over whether governments could realistically enforce age limits on platforms that played a critical role in social life, education, entertainment and communication.

The Albanese government argued the intervention was necessary, citing research linking heavy social media use among younger teens to harmful content, bullying, misinformation and damaging effects on body image.

Other countries have already signalled interest in adopting similar rules. Officials in Denmark, New Zealand and Malaysia have cited the Australian model as a potential blueprint, signalling a wider shift towards tighter age controls in the digital sphere.

Julie Inman Grant, the American-born former tech executive who heads Australia’s online safety watchdog, said demands for stricter measures were rising across the world.

Elon Musk’s X was the latest major platform to confirm it would comply with the ban.

“It’s not our choice – it’s what the Australian law requires,” the firm said. “X automatically offboards anyone who does not meet our age requirements.”

Meta said the ban could send youngsters to less regulated platforms, making them less safe. “We’ve consistently raised concerns that this poorly developed law could push teens to less regulated platforms or apps. We’re now seeing those concerns become reality,” the American company said in a statement.

Platforms say they will use a combination of tools – like behaviour analysis to estimate user age – and age estimation technologies involving selfies to enforce the ban.

They may also require identification documents or linked bank details to verify a user’s age.

Supporters of the ban say such measures are overdue but critics point out that the required data collection risks creating new privacy problems.

For social media firms, the implementation of the ban marks a new era of stagnation as user numbers flatline and time spent on platforms shrinks, studies show.

Platforms say they earn little from advertising to under-16s but warn the ban disrupts a pipeline of future users.

Just before the ban took effect, 86 per cent of Australians aged eight to 15 used social media, the government said.

As of Wednesday morning, several platforms were still in the process of applying the restrictions.

Tests by The Guardian showed that Twitch, Reddit and YouTube continued to permit accounts registered with the birth date of an under-16, while other major platforms had already blocked registration attempts.

Twitch said it was completing testing while YouTube said it was phasing in the changes. Reddit had yet to issue a statement.

Communications minister Anika Wells said that the ban would mark “the moment that sparked a movement”, arguing that industry competition could one day revolve around user safety in the same way that car manufacturers compete on safety standards.

“Big tech could compete, like airlines, like auto manufacturers, to have the best safety record to offer their users,” she said, according to The Guardian.

Richard Waterworth, who served as TikTok’s general manager for the UK and Europe between 2019 and 2024, said the ban risked backfiring.

.jpeg)

He told BBC Radio 4 that although the intention was laudable, the policy represented “a magical thinking solution”.

“Everybody who talks about it seems to acknowledge that it’s not going to work as intended, that there are lots of loopholes,” he said.

Young people, he warned, would simply misrepresent their age and, therefore, lose access to tools designed to keep them safe on platforms.

Children who bypass the restrictions “won’t have access to safety tools”, he said, such as the ability to link accounts to parents or receive age-appropriate recommendations. “I think it’s going to have a lot of unintended consequences, and unfortunately, I don’t think that’s necessarily a win for safety.”

Mr Waterworth also raised privacy concerns about age-verification technologies. “You have to collect data, biometric data, in order to do that and so that is a challenge,” he said. Many people, he added, would not want Big Tech firms “holding their biometric data”.

Andy Burrows, head of the Molly Rose Foundation, named after a teenager who died after exposure to harmful online content, said the UK should avoid copying Australia.

An outright ban might push children to gaming platforms or encrypted messaging sites where monitoring was even more difficult, Mr Burrows argued. “The quickest and most effective response to better protect children online is to strengthen regulation that directly addresses product safety and design risks, rather than an overarching ban.”

While some Australian teens said they planned to spend more time outdoors or meet friends in person, others worried the ban could sever support networks, especially for groups relying on online communities.

“It is going to be worse for queer people and people with niche interests, I guess, because that’s the only way they can find their community,” said Annie Wang, 14. “Some people also use it to vent their feelings and talk to people to get help. So I feel like it’ll be fine for some people, but for some people it’ll worsen their mental health.”

Social media was a big part of people’s lives today, Nick Leech, 15, told the Australian Associated Press, “and taking that away so suddenly is going to definitely cause some issues”.

Ryan Angler, 14, said the ban made him aware of how much he depended on social apps for everyday communication.

“I just wanted to meet up with all my friends but I couldn’t really because I don’t have their numbers before we lost social media,” he told Melbourne newspaper The Age.

After being locked out, he began collecting their phone numbers at school. “I have just been riding around on my bike, playing games on my computer and lying down on my bed because I couldn’t do anything.”

Tania Kaniz, a teaching assistant and mother of two boys, said the ban had dominated conversation at her school.

“They all have it – especially TikTok, if you see it, my God,” she said. As phones are already banned during school hours, she cannot tell whether students are circumventing the new rules. “I think they are, but they don’t want to share it with us,” she said.

At a Sydney event marking the launch of the ban, Mr Albanese praised political rivals for supporting the policy and described a campaign by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp newspapers in favour of the ban as “the most powerful use of print media I have seen for a very long period of time”.

He conceded that the rollout would not be flawless. “We’ll work through it,” he said.

To enforce compliance, the eSafety Commissioner will require the 10 major platforms to provide information on user numbers before and after the ban.

Ms Inman Grant said the platforms should expect a period of trial and error as the law settled in. As some teenagers gloated about bypassing the restrictions, she said it would inevitably occur, but the government was committed to the long-term goal.

The push for the ban was influenced by families whose children were harmed by online content.

Wayne Holdsworth, a Melbourne father whose son died by suicide after being bullied online, said the ban would help prepare teenagers to handle digital spaces when they became eligible at 16.

“Our kids will be looking down with pride, with the work that we’ve done, we have only just started,” he told The Guardian.

Emma Mason, whose 15-year-old daughter Tilly Rosewarne died in 2022, said the ban was not the end of the struggle.

“It’s not going to be perfect, it’s an evolving space, but, good God, it’s a good day to be an Australian,” she said.

Australia’s ban comes as governments around the world grapple with how to regulate social media for young people. Many countries currently rely on parental-consent systems or child-specific settings on devices and apps, though enforcement varies widely.

In the US, federal law prohibits online services from collecting any data from children under 13 without parental consent. In Europe, policymakers are working on plans for continent-wide age-verification rules.

France, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Malaysia have all taken steps towards age restrictions of their own, though none has imposed a full legal ban like Australia.

PM warns of ‘lost decade of kids’ as 10-year youth plan launched

Australia’s social media ban has begun. Here are four ways to stay connected

South Korea to require advertisers to label AI-generated ads

Adding this food to your diet could help restore devastated coastlines

Australia PM tells teens to ‘read a book’ as social media ban comes into effect