I first came across the work of Argentinian underground enfant terrible Marina Otero in 2022, seeing her work Fuck Me in Paris. Fuck Me starts with shaky videos of Otero speaking from a hospital bed while awaiting spinal surgery, explaining her initial absence from the stage.

When she did appear, she was frail and could barely move. Six strapping naked dancers helped her demonstrate what the dance would have been, now that she could no longer dance. Propping and carrying her, her petite body seemed even more fragile in their hands.

We were all commiserating over her misfortune as she was telling us, in random order, about her injury, her loneliness, her sexless life, her grandfather and the military dictatorship in Argentina.

At the end, when she came to bow, she moved so precariously that a gust of wind would have blown her away. And then, as we were getting ready to leave, she stormed back onto the stage and started running in circles, faster and faster, going and going, finally stopping when the last person left the theatre.

I was told it went on for almost an hour.

Never have I felt more emotionally manipulated as an audience member. I appreciated the astuteness of the trickery but was furious at my naivety. For a long time, I thought it was all fiction.

Later, I learnt it was all true; it was indeed Otero’s life, living with pain, joyless and desireless. This is what pain does.

At this year’s Rising festival, Otero’s Kill Me – the last in the trilogy which started with Fuck Me – is also about her life. She gives us the story of a painful breakup with a narcissistic man, the resulting revengeful desire to become an invincible Sarah Connor and Otero’s subsequent diagnosis with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

The rest of the cast have been chosen by Otero because they all live with this condition. Five naked women wear little else than knee-pads, black gloves, white boots and orange wigs, and carry revolvers. They enter the stage majestically and promise to be credible Sarah Connors.

Instead, they turn out to be self-declared Marilyns and Lady Dis, as they each tell us about their life with mental illness.

The piece becomes a catalogue of vignettes and vivid illustrations. Their stories are messy and painful to hear. Yet the unsettling always veers into the hilarious, peppered with flamboyant songs and cheesy Lacan quotes.

And then, there is the great male ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, reborn, performed by the only male dancer, as stoutly robust as Nijinsky was flowingly tall. He is the clown, the cheerful unballetic partner to attempted pirouettes with improbable endings.

As Otero’s final monologue arrives, an account of the plight of living with BPD, and of her intention to end the piece with a gun to her head, I remember Nijinsky’s diary entry:

The audience came to be amused. They thought that I was dancing to amuse them. I danced frightening things.

Otero and her dancers dance frightening things, from the artist’s necessity to create to keep sane, to self harming to feel one has a self, to exhibiting one’s life to feel alive.

This is the story of those too unstable for the “ordered” world, of the many “misfits”, the “insane” and the “hysteric” – all those who need to take a pill to fit into the world, as she says.

This time, Otero’s staged life is not a manipulation of our emotions, rather a diffraction of our own. These sexy avengers and reborn Nijinskys are us, and their fears, ours: fears of being unloved, abandoned, forgotten. Some of us manage to make it “fit” better. Others take it to the stage as both salvation and redemption.

The depression of BLKDOG

BLKDOG, from British choreographer Botis Seva, is also about mental health, suggested by the title, referencing Winston Churchill’s metaphor of the black dogpopularised in referring to depression.

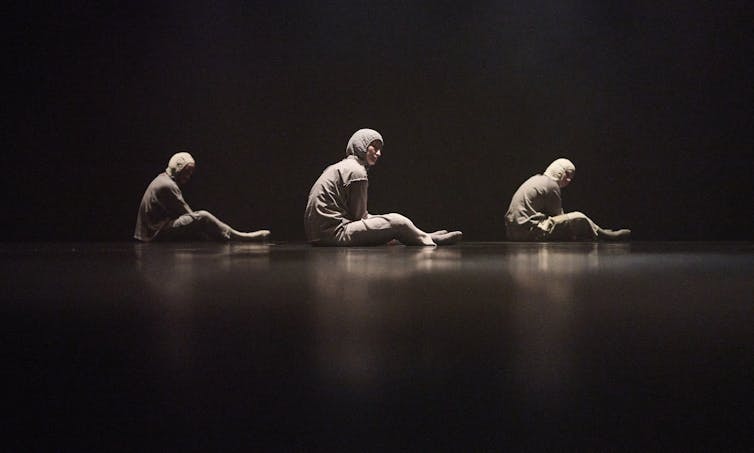

This is a dark piece, contrasting heavily with Kill Me. Seven hooded, genderless bodies emerge from obscurity, move and morph together, a tenuous presence at first, and then more threatening, as the group gangs up on one of them, suddenly, somehow isolated.

It does not become any lighter. The dancers don hoodies for a more urban apparel and, later, dragon onesies.

This unsettling closing in remains a pattern. A lonely body breaks out from the group, to simulate suicide, or self-harm, or murder. The others approaching to attack, rape, beat or kill. The unnerving dancing reveals the dancers’ skills, all impeccably trained in street dance, as the choreography relies heavily on the virtuosic vocabulary of popping and krumping.

Everything is dark and rough in this joyless piece. The lighting that plunges the stage into oppressive mists or aggressively isolates bodies with cutting brightness, the relentless pounding of Torben Lars’ soundtrack, the dancers’ faces always in the dark.

The choreography is a suite of vignettes of simulated violence, but they are so theatricalised it dilutes them into caricature. When tenderness arrives, unexpectedly, with one body consoling another, a gentle movement here and there, a pause softened by children’s voices, it makes us see the depth of the turmoil, the thoughts thumping trapped in one’s head.

It is inescapable and we are glad when the piece is over. Seva created this piece in 2018 after the birth of his first child. He doesn’t want to perform it anymore as it takes him to dark places. Like Otero, he says he had to make the piece. Unlike Otero, he no longer wants his life to be the work.

Oozing with joy

In The Butterfly that Flew into the Rave, from New Zealand Aotearoa choreographer Oli Mathiesen, Mathiesen and his two acolytes, Celia Hext and Tayla Gartner, dance non-stop for nearly two hours on the Buxton Contemporary concrete floor.

There is nothing here of the dancing-till-you-forget-yourself typical of raves; always the same saccadic movements, always the slight sadness, of those who want to keep going in sweaty clubbing rooms when lights go up or, in the early dusty mornings of an ending festival.

There is joy oozing out of this trio’s dancing, facing us, smiling at us, as they swim from one routine into the other, not the tedious spasmodic rave clubbing vocabulary but the more joyful aerobic-whacking-contemporary jazz sort of thing one can learn from YouTube tutorials.

Their joy is infectious as they dance together in sync. When they are not synced, it is in jest. They smile at us as they dance for us. The joy infects the audience: those standing and pulsing to the beat of the music, those who resist it but not for long, those so taken with the dancers that they forget to breathe because they are so attuned.

We are implicated as witnesses to their generous joy, palpable and pulsing like a beating heart. We remember we have one: one that can give in to joy.

In all three works, their protagonists throw their bodies into the fight. They dance with depth and urgency, because they have to, and while the fight may seem different, it may be the same, that of finding (and keeping) the joy.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

As a dance professional, Angela Conquet has received funding from Creative Australia. She is the co-chair of the Green Room Awards Dance panel.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.