Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s promise to power Australia with nuclear energy has been described by experts as a costly “mirage” that risks postponing the clean energy transition.

Beyond this, however, the Coalition’s nuclear policy has, for many First Nations peoples, raised the spectre of the last time the atomic industry came to Australia.

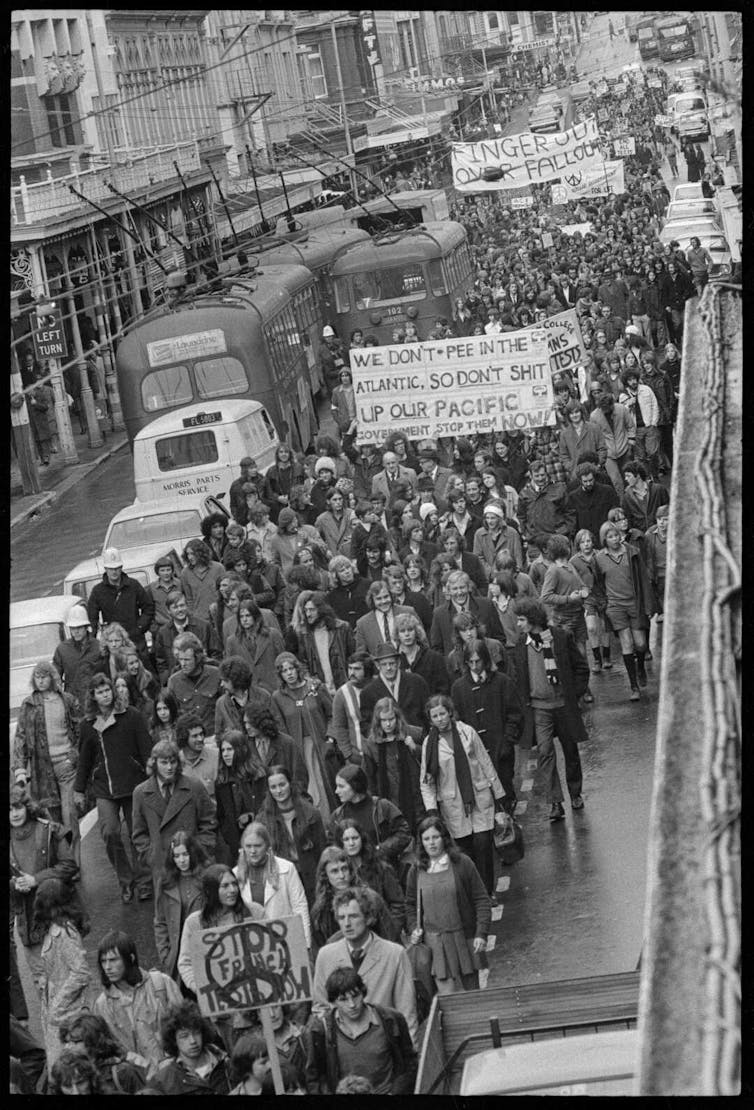

Indigenous peoples across Oceania share memories of violent histories of nuclear bomb testing, uranium mining and waste dumping – all of which disproportionately affected them and/or their ancestors.

Two sides of the same coin

While it may be tempting to separate them, the links between military and civilian nuclear industries – that is, between nuclear weapons and nuclear energy plants – are well established. According to a 2021 paper by energy economists Lars Sorge and Anne Neumann: “In part, the global civilian nuclear industry was established to legitimatise the development of nuclear weapons.”

The causative links between military and civilian uses of nuclear power flow in both directions.

As Sorge and Neumann write, many technologies and skills developed for use in nuclear bombs and submarines end up being used in nuclear power generation. Another expert analysis suggests countries that receive peaceful nuclear assistance, in the form of nuclear technology, materials or skills, are more likely to initiate nuclear weapons programs.

Since the first atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945, Indigenous peoples across the Pacific have been singing, writing and talking about nuclear colonialism. Some were told the sacrifice of their lands and lifeways was “for the good of mankind”.

Today, they continue to use their bodies and voices to push back against the promise of a benevolent nuclear future – a vision that has often been used justify their and their ancestors’ suffering and displacement.

Black mist and brittle landscapes

In 2023, Bangarra Dance Company produced Yuldea. This performance centres on the Yooldil Kapi, a permanent desert waterhole.

For millennia, this water source sustained the Aṉangu and Nunga peoples and a multitude of other plant and animal life across the Great Victorian Desert and far-west South Australia.

In 1933, Yuldea became the site of the Ooldea Mission. Then, in 1953, when the British began testing nuclear bombs at nearby Emu Field (1953) and Maralinga (1956–57), the local Aṉangu Pila Nguru were displaced from their land to the mission.

Directed by Wirangu and Mirning woman Frances Rings, Yuldea tells the story of this Country in four acts: act one, Supernova; act two, Kapi (Water); act three, Empire; and act four, Ooldea Spirit.

The impacts of nuclear testing are directly confronted in a section titled Black Mist (in act three, Empire). Dancers’ bodies twist and spasm as a black mist falls from the sky, representing the fog of radioactive particles that resulted from weapons testing. In reality, this fog could cause lifelong injuries when inhaled or ingested, including blindness.

But Yuldea is more than just a story of destruction. By exploring Aṉangu and Nunga relationships with Country before and after nuclear testing, it affirms their enduring presence in the region. This is captured in the opening prose:

We are memory.

Glimpsed through shimmering light on water.

A story place where black oaks stand watch.

Carved into trees and painted on rocks.

North - South - East - West.

A brittle landscape of life and loss.

To acknowledge is to remember

The podcast Nu/clear Stories (2023-), created by Mā'ohi (Tahitian) women Mililani Ganivet and Marie-Hélène Villierme, uses storytelling to grapple with the consequences of colonial nuclear testing.

Ganivet and Villierme address the memories of French nuclear testing on the islands of Moruroa and Fangataufa in Mā’ohi Nui (French Polynesia) from 1963 to 1996.

Rather than using a linear understanding of time, which keeps the past in the past and idealises a future of “progress”, Nu/clear Stories draws on Indigenous philosophies of cyclical or spiral time to insist that by turning to the past, we can understand how history shapes the present and future.

As Ganivet says when introducing the first episode, Silences and Questions:

We are part of a long genealogy of people who found the courage to speak before us. […] To acknowledge them here is to remember that without them we would not be able to speak today. And so today, we stand on their shoulders, with the face firmly turned towards the past, but with our eyes gazing deep into the future.

Stories in the Tomb

In her 2018 poem video Anointed, Part III of the series Dome, Marshall Islander woman Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner pays homage to Runit Island. This island in the Enewetak Atoll was transformed into a dumping site for waste from US nuclear bomb tests between 1946 and 1958.

A huge concrete dome was built on Runit Island in the 1970s to cover about 85,000 cubic metres of radioactive waste. The island became known as “the Tomb” to the Enewetak people – a tomb that still leaks nuclear radiation into the ocean today.

However, like the creators behind Yuldea and Nu/clear Stories, Jetn̄il-Kijiner refuses to remember Runit Island as only a nuclear graveyard. Instead, she approaches it like a long-lost family member or ancestor who she hopes will be full of stories.

Jetn̄il-Kijiner speaks to the island through her poem, drawing a devastating contrast between what it once was and what it is now:

You were a whole island, once. You were breadfruit trees heavy with green globes of fruit whispering promises of massive canoes. Crabs dusted with white sand scuttled through pandanus roots. Beneath looming coconut trees beds of ripe watermelon slept still, swollen with juice. And you were protected by powerful irooj, chiefs birthed from women who could swim pregnant for miles beneath a full moon.

Then you became testing ground. Nine nuclear weapons consumed you, one by one by one, engulfed in an inferno of blazing heat. You became crater, an empty belly. Plutonium ground into a concrete slurry filled your hollow cavern. You became tomb. You became concrete shell. You became solidified history, immoveable, unforgettable.

While Jetn̄il-Kijiner describes herself as “a crater empty of stories”, she continues to find stories in the Tomb: namely, the legend of Letao, the son of a turtle goddess who turned himself into fire and, in the hands of a small boy, nearly burned a village to the ground.

Juxtaposing this fire with the US’s nuclear bombs, she ends her poem with “questions, hard as concrete”:

Who gave them this power?

Who anointed them with the power to burn?

The link between past and future

In their book Living in a nuclear world: From Fukushima to Hiroshima (2022), Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and others explore how “nuclear actors” frame nuclear technology as “indispensable”, “mundane” and “safe” by neatly severing nuclear energy from nuclear history.

This framing helps nuclear actors avoid answering concrete questions. It also helps to hides the colonial history of nuclear technologies – histories which leak into the present. But not everyone accepts this framing.

Indigenous artists remind us the nuclear past must be front-of-mind as we look to shape the future.

During her PhD thesis – funded by the Australian Government Research Training Program – Josephine worked on photographic works by Marie-Hélène Villierme. She has also interviewed Villierme in the past, and worked with her collaboratively on a book chapter on her work (published in Francophone Oceania Today (2024)).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.