Academic researchers have concluded that 100% of all the arts coverage of suicide they studied in British newspapers breached guidelines, reports Roy Greenslade in The Guardian. Specifically, they looked at 68 articles about the artists Vincent van Gogh, Mark Rothko, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Arshile Gorky, who all killed themselves. Every single story, they claim, ran roughshod over advice from the Samaritans, MediaWise Trust and Ipso by not including information on support lines, while many articles ran the risk of romanticising or glorifying suicide.

They single out two articles by Waldemar Januszczak, but I don’t see why the Sunday Times critic should stand alone. I’d like to draw attention to one of my own articles about Mark Rothko, which begins with a detailed description of the artist being discovered “lying dead in a wine-dark sea of his own blood”.

I make no apology and nor should other critics.

The deaths of Van Gogh and Rothko are historical facts. Surely a statute of limitation has passed. Asking a critic to tiptoe around the suicide of Van Gogh in 1890, or insisting that such articles must include information on support for those affected by this terrible phenomenon, is like asking historians to be careful in writing about the Boer war (1899-1902) and to add information on what to do if you are in a war situation. Or if 1890 still seems close, what if I were to write about the suicide of the Renaissance artist Rosso Fiorentino in 1540?

There is clearly a difference between contemporary news and history. It is absolutely right to exercise caution in reporting suicide and discussing it. Yet even writing that, I feel slightly dishonest. The only duty of journalism is to be truthful. The claim implicit in this study, and indeed in the media guidelines, is surely similar to the argument that representations of violence in cinema cause violence on the streets. Actually it is the same argument, for suicide is a very dangerous form of violence. But is it therefore harmful to represent it? If so, then Gertrude, we need to talk about Hamlet.

Accusing critics of celebrating suicide is counterproductive. The reason this subject comes up so often in our work is that it is so deeply embedded in cultural history.

“To be or not to be …” The greatest dramatic speech in the English language openly considers suicide as a legitimate and meaningful act. Hamlet suggests that only the fear of hell stops people taking their own lives. Otherwise:

“who would bear the Whips and Scorns of time,

The Oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s Contumely,

The pangs of despised Love, the Law’s delay,

The insolence of Office, and the Spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his Quietus make

With a bare Bodkin?”

Shakespeare here portrays suicide as something to be considered by any rational mind. Should productions of Hamlet be stopped at this point for an audience discussion led by trained counsellors?

Other great writers and artists have shared his challenging perspective on this subject. In the Greek philosopher Plato’s account of the trial and death of his master Socrates, the provocative Socrates puts on such an aggressive, taunting defence that he practically courts a death sentence. Urged to escape, he instead calmly drinks poison. David’s 1781 painting The Death of Socrates clearly sees this act as heroic. Should the Metropolitan Museum remove it from view?

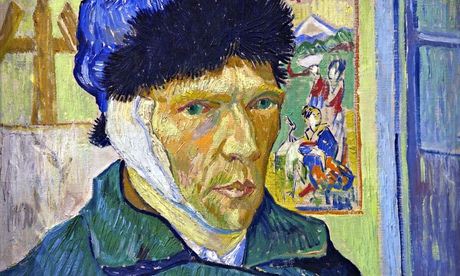

Similarly, the Courtauld Gallery in London exhibits Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear. This painting frankly displays the result of Van Gogh’s act of physical self-harm. This violence against himself looks especially disturbing in the light of his suicide the following year. I would say it makes self-harm look heroic, if only in Van Gogh’s readiness to look himself in the eye. Should it be hidden in a storeroom?

It is patronising, disrespectful and belittling to think that people cannot talk about, think about, write about and read about the suicides of artists, and the portrayal of suicide in the arts, in an open and uninhibited way.