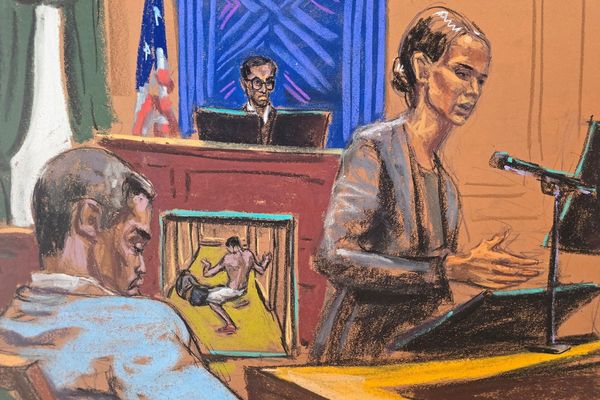

Cartoonist and illustrator Renan Ortiz is one of many Filipino artists to have picked up a pen, pencil or paintbrush in defence of journalist Maria Ressa, who was convicted of “cyber libel” in June and could face a prison term.

Ortiz drew a cartoon of Ressa holding a “Defend Press Freedom” poster, and uploaded it to his Instagram account.

The conviction of Ressa, the co-founder and chief executive of online news website Rappler, came ahead of the enactment of a much feared anti-terrorism bill in the Philippines, which is set for July 9. Seen by many as a means to brand political opponents terrorists and to silence free expression, the bill has been met with widespread public opposition.

Ortiz says the government of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte uses a range of tactics against journalists and outspoken artists, including killing them, harassment, and using “black propaganda” to defame them.

“We all know the bill will not target terrorists. It will target all opposition,” Ortiz says. “It will act as a final sweep, the clean-up, the red carpet for the Duterte dictatorship.”

Supporters of the bill point to violent attacks that have rocked the nation in recent months. They insist the Philippines’ 2007 Human Security Act is too restrictive and hinders the government’s ability to effectively combat terrorists and their supporters. Duterte has flagged the anti-terror bill as “urgent”.

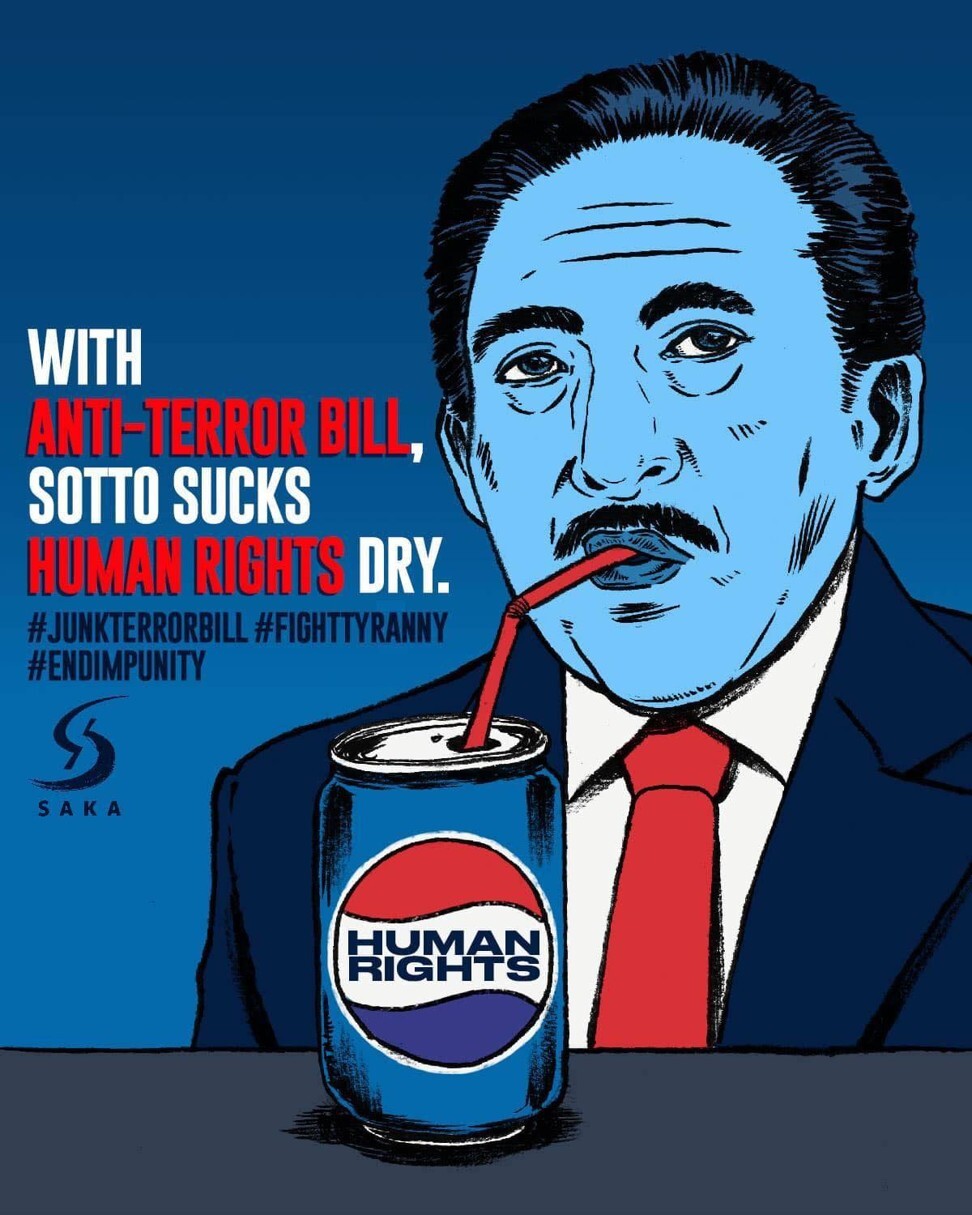

Public opposition to the bill was evident at a June 12 Independence Day demonstration in Metro Manila, where an array of eye-catching signs, face masks and banners expressed dismay and outrage.

National police chief Debold Sinas, who was given special permission to hold a birthday party despite a ban on mass gatherings, was mocked by members of the artist-activist group SAKA (Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo), who lugged a “karaoke resistance” set around the protest.

SAKA writer Angelo Suarez points to a number of links between collective resistance and art. With limited tools and with movement restricted by quarantine measures, artists continue to make the most of what’s available to them, he says, adding that their art can be “as simple as a social media post, but is most effective in print for maximum distribution to grass-roots communities”.

Professor Lisa Ito, secretary general of Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP), says the anti-terror bill “casts a wide net” and endangers art and creativity.

Ito, an academic at the University of the Philippines, says artists should safeguard democratic values.

“The bill is the largest threat to constitutionally protected freedom of expression, which we hold dear as artists and cultural workers,” she says. It is essential artists are able to “freely express, create and tell the truth, especially to power”, she says.

The challenge is how to compete with government censorship and propaganda, which has more reach but is either unintelligent or misleading or malicious - Cartoonist and illustrator Renan Ortiz

“The bill’s vague provisions make it easy for the state to target artistic and creative productions, especially critical, satirical or protest forms it subjectively deems as anti-government or subversive – or terrorist, in today’s cruder parlance,” Ito says.

CAP was founded in 1983 in response to the martial law imposed in the Philippines by another strongman president, Ferdinand Marcos. Ito says life under Duterte now mirrors the country’s martial law era, so in response CAP has made strides in coordinating artistic production, discussion and paralegal training. The group helped organise the June 12 demonstration and helped organise a joint statement of more than 1,500 artists and groups opposed to the anti-terror bill.

Cartoonist Ortiz, who is also an art teacher, insists his work and his message will not change when the bill becomes law, and agrees with his peers that cultural workers have a social obligation to shine a light on unwelcome truths.

“I’m protected by a constitutional right to free expression, which is more powerful than an ordinary law,” he says. “The challenge is how to compete with government censorship and propaganda, which has more reach but is either unintelligent or misleading or malicious.”

The Duterte administration’s case against Ressa is an attack on free speech, he adds. “But we must not forget, even without the anti-terror bill, the Duterte government has made headway in dismantling opposition and targeting critics.”

Comic-creator and illustrator Electromilk, who posts minimalist strips on social media, is another frequent critic of the bill. “The government has no interest in nor understanding of art and culture whatsoever,” he says.

Many of his recent posts have dealt with the frustration of being ruled by a government more interested in policing free expression than helping its citizens, as the country continues to reel from the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I like making online comics and illustrations that express how I feel for the country and the circumstances we are going through,” he says. “Sometimes they are also a plea for my fellow countrymen to practise empathy and have a wider perspective on things.”

An artist at the Independence Day rally, Miguel Robleza of the Katipunan Kreative group of civic-minded designers and researchers, insists his work will not change when the anti-terror bill becomes law.

“Of course not. Isn’t that what artists are supposed to do?” he says. “To critique the wrongs around us?”

These artists may be treading a dangerous road. Even before the law is enacted, any criticism of Duterte has been a target for retribution. In February, a film titled Walang Kasarian Ang Digmang Bayan (The Revolution Knows no Gender) was abruptly pulled from the 2020 Sinag Maynila Film Festival, co-founded by Duterte stalwart Brillante Mendoza.

The story of a filmmaker who becomes a revolutionary after the murder of his nephew in the Philippines’ brutal war on drugs, Walang Kasarian Ang Digmang Bayan echoes much of the criticism of the police force’s indiscriminate campaign against narcotics. The war on drugs has left thousands dead, mostly the urban poor.

In one of the film’s scenes, a bereft mother who has lost a child says: “If I were just a bit braver, I would kill Duterte myself.”

A director himself, Mendoza has filmed Duterte’s state-of-the-nation addresses, and previously made a television series that carried an anti-drugs message. He has now been accused of censorship for disqualifying the festival entry.

The festival’s executive committee announced that Walang Kasarian Ang Digmang Bayan had been pulled because there was “substantial deviation” from the approved script. “The film is no longer a faithful representation of the approved screenplay,” it stated.

On his Facebook page, however, director Joselito Altarejos insisted the film had been censored for other reasons, describing the disqualification as “a flimsy way out to get rid of me and the film”.

Artists and cultural workers engaged with marginalised sectors in the community can face severe consequences for any activism. On April 19 in Cebu, writer Bambi Beltran was arrested without a warrant for allegedly posting fake news online – her satirical take critical of the local government’s response to the spread of Covid-19 in one particular town.

CAP secretary general Ito says Marlon Maldos, a choreographer with the cultural group Bansiwag and an advocate for land reform in the province of Bohol, was gunned down on the national highway in Bohol in March. Maldos had used the medium of dance to push for reform, and many people suspect he was killed by state forces opposed to his message.

Ito says the incident had been preceded by red-tagging and harassment of activists by the 47th Infantry Battalion. Government critics in the Philippines are often branded as communist, regardless of their politics, and “red tagged” for their so-called political allegiances or activism.

In the end, Ito says, both art and freedom of speech have an essential role to play in any civilised society.

“Artists are here to attest to the core of what is being attacked in the end, the heart and spirit of society, and the right to expression which makes us free,” she says.