Context can be all in live performance. Where and when a show is happening can be as much a contributory factor to the way it’s received as the script, director and design. A piece that works well in one space may falter when moved to another space – or indeed to another culture or country. Think of the lack of success of The Pitmen Painters in Dublin when it had been widely praised in the UK. What we know or are told about a performance in advance can also influence our reaction to it, and that’s particularly true when sex and violence are concerned.

We all take the outside world into a performance with us. When during an outdoor circus performance at Greenwich and Docklands international festival the other week one of the characters produced a rifle, it simply didn’t feel comical – as it was intended to be – because it was just 24 hours after the Tunisian killings. Should we have been warned in advance in case it caused offence? I don’t think so.

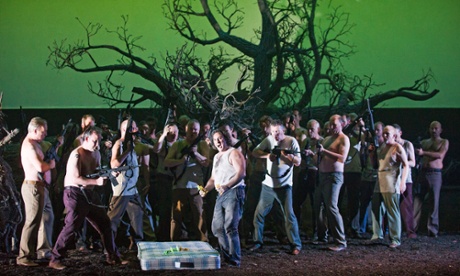

Context may in part explain what happened at the Royal Opera House during Damiano Michieletto’s production of Guillaume Tell last week when the audience started booing loudly during a graphic scene in which a woman is stripped and raped. As Zoe Williams has intimated it may be that they were booing acts against Rossini rather than acts against women. Booing is of course much more common among notoriously conservative opera goers than it is in theatre, where audiences simply tend to show their disapproval by leaving politely at the interval or falling asleep. It’s possible that at the ROH the rape scene became a flashpoint in a poorly received four-and-a-half-hour production that was clearly already testing the patience of the audience.

As I’ve written before, there is undoubtedly a place for violence on stage because there is violence in the world and if theatre has any relevance to the world it has to reflect it. Not doing so, merely ensures that it continues to take place hidden from view and that the social structures that allow it to happen continue to flourish. Deborah Orr makes this point very well.

Michieletto initially declared that he had no intention of changing his revival in any way, although he appears to have relented, saying that “if you don’t feel the brutality, it becomes soft, it becomes for children”. But that’s not always true. Greek theatre may have had it right in banishing violence offstage so it becomes magnified in our minds. But of course the ancient Greeks didn’t have TV news or beheading videos, and some argue that in a world of everyday extreme violence we have inevitably lost touch with the Greek model.

Often we don’t need a stage awash with gore and physical violence to be really disturbed. In John Doyle’s revival of Sweeney Todd, death came gut-wrenchingly with a bucket of red blood poured into another bucket. In Robert Icke’s Oresteia at the Almeida the sacrifice of Iphigenia by her father is so cool and clinical it is almost unbearable to watch.

The ROH’s director of opera, Kasper Holten, has said that the pre-performance warning for Guillaume Tell will be reviewed so audiences are more prepared for the scene. But doesn’t the increasingly common warning about a show’s sex and violenceimmediately change audience expectations and the context in which the sex and violence will be received?

Audiences were warned in advance publicity that Jennie Webb’s comedy Rebecca on the Bus was about rape. Tiffany Atone, whose company staged the piece, has written a really interesting article in which she explores whether the warning compromised or neutered their response to it. She writes: “The trigger warning seemed to serve as a muffler for our audiences during performance, as though it left them stifled with responsible notions of what is and is not allowably laughable, preventing them from indulging in the play’s humour. The result was an audience both quiet and uncomfortable before the play had hit the gut-punch point that was supposed to leave them squirming.”

It’s a lesson worth taking to heart because art that fears offending its audience in any way is art that infantilises both itself and the audience. It would be a pity if the fuss over Guillaume Tell led to caution in all live performance. Better a few people end up being offended than everyone watching is poleaxed by indifference.