Anne Weston, LRI, CRUK

It looks a radioactive hazard warning. In fact, this delicate assembly of triangles is a scanning electron micrograph of a diatom. Diatoms are single-cell organisms that are one of the most common types of phytoplanktons and play a major role in sustaining life on Earth. Although usually too small to be seen with the naked, phytoplankton form green blooms on the sea and convert sunlight and carbon dioxide into oxygen. They also provide food for a large number of aquatic species. Diatoms are encased within a hard cell wall made from silica, which is known as a frustule and is composed of two halves. Frustules have a variety of patterns, pores, spines and ridges, which are used to determine genera and species. The health of communities of phytoplankton is measured carefully by scientists because they provide useful indications of environmental conditions such as water quality Photograph: Wellcome Images

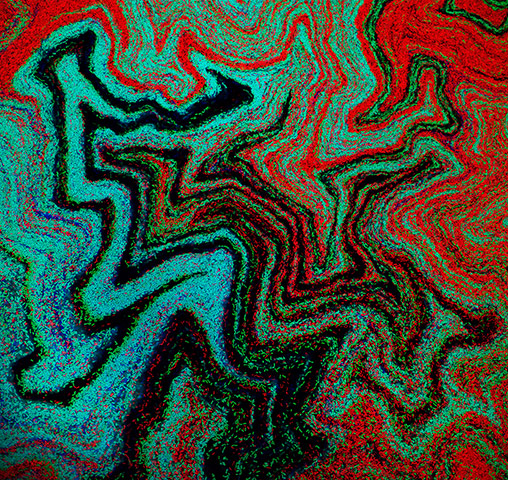

Fernan Federici, Tim Rudge, PJ Steiner and Jim Haseloff

This is Bacillus subtilis, a rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in soil. Distinct lineages of bacteria expressing different fluorescent proteins were initially mixed randomly on a petri dish. As bacteria grow, they organise themselves into reproducible patterns and shapes that can be predicted with mathematical models. The researchers took this image as part of a project designing artificial genetic circuits for pattern formation in bacterial colonies and plant tissues Photograph: Wellcome Images

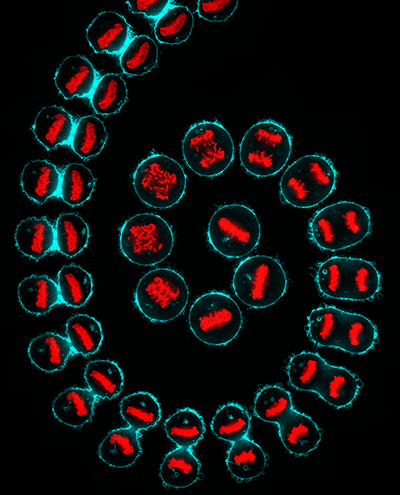

Kuan-Chung Su, Cancer Research UK, London Research Institute

This striking, spiralling sequence was created using time-lapse photography to show the process of division – known as mitosis – of a cancer cell over a period of an hour. In the centre of the shot, the first stage of the process is captured, with the red DNA encircled by a near-perfectly round cell membrane. The DNA begins to duplicate, and to separate within the cyan enclosure. With the identical copies of DNA at opposite ends of the cell, gradually the membrane contracts. The subtle developments from one snapshot to the next follow the two daughter cells as they split away from one another, ready to undergo the same process themselves roughly 16 hours later Photograph: Wellcome Images

Annie Cavanagh

These may look like tomatoes ripening on the vine but scale is misleading. This scanning electron micrograph shows a lavender leaf (Lavandula) that is only 200 microns across, roughly a 50th of a centimetre. Lavender is native to much of Africa, Asia and Europe and is a favourite ornamental plant in Britain. It produces an oil that has a distinctive sweetness and is used in balms, salves, perfumes, cosmetics and topical applications. It is also claimed that it can be used to aid sleep and to alleviate anxiety. The oily secrets of lavender are revealed in this striking image which shows the surface of a leaf covered with fine hair-like outgrowths made from specialised epidermal cells called non-glandular trichomes. These protect the plant against pests and reduce evaporation from the leaf. Glandular trichomes are also present, containing the oil produced by the plant Photograph: Wellcome Images

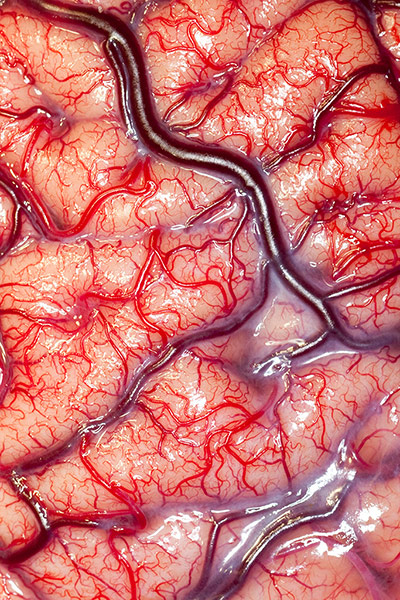

Robert Ludlow, UCL Institute of Neurology, London

This surface of the human brain in explicit detail and comes from an epileptic patient in the lead-up to a major surgical operation. The image marks the first step in a process of analysis required to identify the area of the brain that needs to be removed. When it was taken, the patient was fitted with an electrode grid to monitor and record the activity of the brain for up to two weeks. After this time, surgeons were able to identify the section of the brain responsible for epileptic fits, and remove it Photograph: Wellcome Images

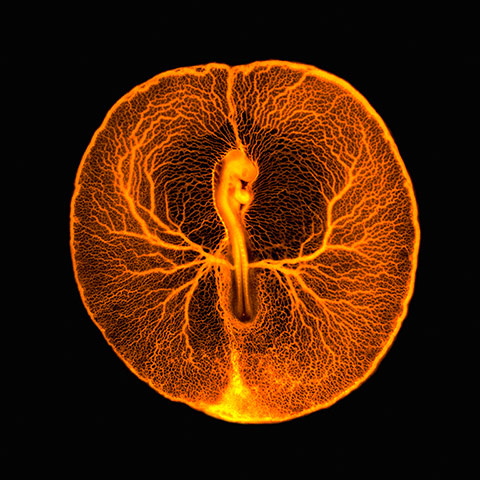

Vincent Pasque, University of Cambridge

The ethereal organism in the centre of this image is a newly fertilised chicken, captured just two days into its embryonic existence. The surrounding haven of blood vessels, known as a vasculature, acts as a tiny life support mechanism to the developing creature, which at this stage is roughly the size of a five pence piece. This network of veins and arteries connects the chicken to the rest of the egg, enabling the embryo to feed on the rich underlying yolk. The embryo already displays a tiny heart and brain. The trailing bottom half of the organism will become the chicken’s body on which its wings and legs will emerge Photograph: Wellcome Images