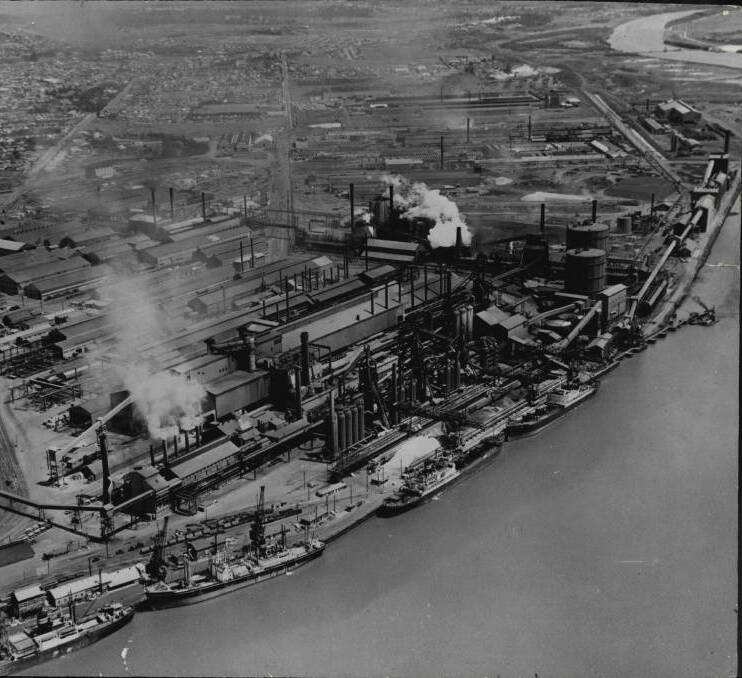

AS he surveys the swathe of land at Mayfield that hosted the BHP steelworks for almost 85 years, Craig Carmody sees not so much dormant property but the far trickier terrain of a dream constrained.

On the bank of the Hunter River's south arm, where iron ore was once unloaded from vessels and steel products shipped out around Australia and the globe, the Port of Newcastle CEO envisions a container terminal.

As the world looks to move beyond coal, Mr Carmody sees that terminal as part of the port's, and the city's, future. .

"Land size, we'll consume the entire 100 hectares," Mr Carmody says. "There will also be a distribution centre here. There will be rail sidings."

He predicts the facility will be able to handle about two million containers annually.

But what Craig Carmody sees for this portside land is not exactly a vision shared by the NSW government.

Nine years ago, as it set about privatising a number of ports, including Newcastle's, the state government did a deal with members of a consortium known as NSW Ports, the new owner of Port Kembla and Port Botany, which handles the vast bulk of containers in the state.

The agreement protects NSW Ports from having to contend with a competing container terminal being established in Newcastle. If Port of Newcastle developed a terminal and exceeded a cap on the number of containers it handles, the state would have to pay a fee to NSW Ports. Then Port of Newcastle would have to reimburse the state.

The deal, and the length it runs, exasperates Craig Carmody, who describes it as "a disgraceful act on the future of the Hunter".

"This deal runs till 2065," Mr Carmody says. "That's a second generation away. I mean, Good Lord!

"We're watching the economy of Australia decarbonise, and the NSW Government wants the port of Newcastle to remain the world's largest coal port. Are we kidding ourselves here!?"

The issue has been played out in the courts and in state parliament for years, so, for the moment, the Port of Newcastle CEO has had to rein in the container terminal vision.

But he doesn't view this harbourside land as a burial ground for an idea that the government perhaps wishes was dead.

Instead, at the berth known as Mayfield 4, the dream of the Newcastle Deepwater Container Terminal has been not so much exhumed as risen to life.

On this fine winter's day, Craig Carmody has been celebrating the arrival of two mobile harbour cranes, which are being cradled on the deck of a ship that has voyaged from Germany.

The two cranes will have the ability to lift one 40-foot container in a single move.

Yet, in ways they haven't been designed for, the cranes are going to be put to use lifting far more than a container. Craig Carmody hopes to lift the need and desire for a container terminal into the line of sight of a state government that has resisted looking towards Newcastle.

So he sees the cranes as a "symbol" and a "statement" to the NSW government, demonstrating what is not just possible and viable but vital for the Hunter and further afield.

He says about 450,000 containers are filled in the port's catchment area each year for export, and most of those go to either Port Botany or even over the border to Brisbane to be shipped. And there are the imports that come into Sydney then have to be transported to places such as Newcastle.

The present arrangement, he argues, is costing importers, exporters, shipping lines and consumers. If there was another entry point, there would be "natural competition", and that is better for everyone.

"I didn't think in the year 2022, I would still have to argue these most basic economic fundamentals to the state government," Mr Carmody says.

"There is a desire for people to have competition in the NSW container industry. There is a need to find an alternative to what is literally the inefficiencies and the bottlenecks in Botany.

"Fifty per cent of all the cotton grown in this state this year went through the port of Brisbane. What are we doing? Here, at the port of Newcastle, we're trying to make sure that NSW farmers grow their product, get it to the shortest distance port they can, which is the port of Newcastle, and out to the market."

Newcastle lord mayor Nuatali Nelmes shares the view that the container deal is "really not fair for Novocatrians, but it's also not fair for the northwestern farmers".

"It's actually cost them at least 30 per cent more to get their products to market," Cr Nelmes says. "And if you want to diversify our agricultural industry, you want to provide quality access for our farmlands and overseas markets, the port of Newcastle is probably the best place to do that."

The two mobile cranes at the Mayfield 4 berth are expected to begin operating in September. To remain under the cap imposed by the government's deal with NSW Ports, the cranes will initially handle about 40,000 containers. Craig Carmody says a park for empty containers will also be established.

So the dream of a container terminal is taking shape, even if it occupies nowhere near the amount of land nor the presence in the market that the Port of Newcastle CEO believes is needed.

"Oh! What this city and region needs versus what I'm allowed to do is chalk and cheese," he says.

THE old steelworks site at Mayfield is hardly the only piece of dirt around the port that demonstrates the gulf between what could be and what is.

By Craig Carmody's reckoning, of the 777 hectares of land under Port of Newcastle's control, 388 hectares is vacant. In other words, half of Port of Newcastle's land is inactive. Mr Carmody says, only a tad facetiously, he emits "a small, little sob" every time he looks at all that dormant land.

But he is keen to share the view of what is possible.

"Every investor I have taken up in a helicopter, when you show them the land of the port, you fly over Mayfield, but then they see Tomago, ... they see all these other heavy industries, all surrounding the port," he says. "By the time that chopper has landed, I can promise you, the number of investors who have gone, 'Oh yeah, I want a piece of this. I can see what you're saying'.

"That sums up the Hunter. Our biggest problem is we know what we've got. But outside of the Hunter, I would argue a lot of people do not realise the jewel in the ground that we have here."

There are proposals and plans attached to some harbourside land, including looking at creating a hydrogen production and export facility on Kooragang Island. Corporate and government money and expertise have been directed towards establishing a hydrogen hub.

On its website, Port of Newcastle argues it is "well placed to develop a hydrogen hub and export hydrogen as a tradable energy commodity". What is now predominantly a coal port could "play a substantial role in Australia's bid to become a significant renewable exporter".

Newcastle lord mayor Nuatali Nelmes sees the intersection of dormant port land and the search for energy sources other than coal as a grand opportunity for the region, not just with hydrogen but also off-shore wind farms.

Companies and the federal government have been looking at the possibility of harnessing the wind off the Hunter's coast. According to Cr Nelmes, that could bring benefits from over the horizon into the heart of Newcastle.

"It's a great opportunity for jobs, and good jobs, in the port of Newcastle," she says, forecasting the development of that industry could provide a boost to local manufacturing.

"We are good at manufacturing here, and particularly in the maritime industry around Newcastle. The opportunity is to not just import the types of turbines and blades that you need, [but] to actually manufacture them here.

"There's also the secondary industry, in terms of the maintenance of that type of facility."

The lord mayor says a move to wind energy generation, and the work attached to it, could help provide a path of transition for those working in the coal industry and wondering what their future holds.

"And that is the really important component, you're talking about people's lives and their livelihoods," Cr Nelmes says. "You cannot take that away for an individual, for a person, for their families without having a just plan. And that is why people talk about the transition, and in such a passionate way, because you're actually talking about people's lives."

Still, for all the planning and talk of a transition, Cr Nelmes is under no illusion that the coal trade is going to disappear from the harbour any time soon.

"The usage of the port of Newcastle as a coal port has been around for my lifetime and yours, and I imagine will likely see out my lifetime," she says. "The important component of work that has happened with many different levels of government, as well as advocates around this, is the importance to diversify the economic opportunities to the port."

JUST across the river from the container terminal site, the present economic powerhouse flows incessantly on.

The Kooragang Island shoreline is the epicentre of the world's biggest coal export port.

The industrial behemoth that is Kooragang was once an archipelago of small islands. Those who lived on the fragments of land in the Hunter River estuary were fiercely proud of being "islanders" and many drew a living from the soil and the river, as farmers, fishers and boatbuilders.

But the flood of progress, and the demands of big business, whooshed down the river in the years after World War Two, and many of the islands were subsumed and buried to create the Kooragang precinct.

In 2018, one of those proud islanders, the author and historian Vera Deacon, spoke with me about the loss of her former home for the sake of industry.

"I lament it," she said, "because I feel what was done to the estuary and the islands was definitely a crime against nature".

The ghosts of islands lie under mountains of coal. The little boats the islanders once rowed across to the "mainland" have been replaced by massive ships up to 300 metres long, waiting to carry away those mountains.

Kooragang has been a coal export hub only since 1984. Yet Newcastle has always been a coal-powered port. The first ever commercial export from the British colony of New South Wales was a load of coal shipped from the mouth of the Hunter River to Bengal in 1799.

No sooner was the coal trade underway than businesses and the authorities were trying to work out ways to mine and ship more of the precious black rock, and quickly. Quoting from historian Rosemary Melville's book, A Harbour from a Creek, in Newcastle port's early days, a Sydney Morning Herald journalist complained, "The coal is doled out in miserable thimblefuls and drawn about the wharf in wheelbarrows".

The loads have grown from a thimbleful, with 156,665, 674 tonnes of coal being exported from the port of Newcastle in 2021. The growth in demand for Hunter coal has been extraordinary. In 1975, 10 million tonnes were exported.

A string of berths along Kooragang is devoted to the loading of coal. The terminal furthest up the river is operated by Newcastle Coal Infrastructure Group.

Downstream, operating three ship loaders and with five berths at Kooragang, along with two loaders over at Carrington, is Port Waratah Coal Services (PWCS).

The largest coal exporter in the port, PWCS last year loaded 1279 ships, a record number of vessels, with 111.3 million tonnes of coal, 93 million of which poured out of the loaders on Kooragang.

According to Andrew Dobbie, PWCS' logistics coordinator, the company loads, on average, 100 vessels a month.

"I think each ship averages about 90,000 tonnes," explains Mr Dobbie. "And the ship loaders here at Kooragang [load] 10,500 tonnes an hour. So it's a lot of maths."

The maths take on bewildering dimensions about a kilometre away, where the coal is received and stockpiled. Trains travelling from 25 mining operations in the Hunter Valley and beyond unload coal here.

Our guide around the PWCS terminal is Trevor Simmons. He's had a connection with the company since 1982. Back then, he wasn't a tour guide but a mechanical engineer.

Before taking us to the wharves, Mr Simmons drives around the coal "stockyard". This area consists of four pads, each three kilometres long, with the coal being piled and fed onto conveyors by monstrous machines called stackers and reclaimers. Recycled water is sprayed on the coal piles to suppress dust, creating rainbows. The pot of gold at the end of each rainbow is the coal itself, with it being traded recently at more than US $400 a tonne.

"From an operational point of view, we can hold about two and a half million tonnes of coal on the ground here, all destined to be exported," Mr Simmons says.

That destiny is realised at the other end of the conveyors, down at the wharves. Earlier in his career, Trevor Simmons was involved in the construction of the berths and the installation of the loaders. He recalls how the harbour had to be deepened to accommodate ships.

"The water was only about three metres deep ... where the wharves are built, and we had to dredge the area down to 18 metres, so that the ship can sit there and be loaded and go up and down with the tides and not touch the bottom," Mr Simmons explains.

The sand dredged from the harbour bed helped form the base of what would become the stockpile area. So the stored coal effectively sits on the harbour.

Trevor Simmons explains why there are three ship loaders but five berths at the PWCS facility.

"Ships need to leave by the turn of the high tide, and so if a ship is finished loading and misses the turn of a high tide, it's got to wait another 12 hours before it can leave," he says. "So it's limiting the ability to do ship loading.

"With five ships here, once one ship is finished, the loader can immediately go up and start loading the other ship. And when the tide is right, that other loaded ship can leave and another one [can] come in and take its place. So you get a higher utilisation of the ship-loading equipment."

On this day at K5, a loader is leaning over the United Sapphire, filling the bulk carrier with coal.

"There's a discharge chute that goes down below the deck of the vessel, which is part of the environmental control," says Trevor Simmons.

The loader, he explains, is "half loading every hatch and then comes back and tops up each of them to fill the ship". The United Sapphire has seven hatches to fill.

Andrew Dobbie, whose job involves ensuring the trains and ships keep coming and going so that the coal keeps flowing, finds the loading process "mesmerising".

"Any opportunity I get to be able to go on a ship and look into the hold is great, because the scale of the vessels is just amazing," Andrew Dobbie says. "Just looking into one of the empty hatches, it's like an Olympic-size swimming pool.

"It's pretty mesmerising, just the sheer amount just flowing through and just falling neatly into piles, filling up the hatch nice and evenly."

Trevor Simmons believes this process will continue for many years yet, and that the coal ships will continue to come and go in Newcastle harbour.

"As I understand it, we have an ever increasing demand for energy throughout the world," he says. "And if we look at the demand, coal will be supplying energy for the next 50 years, at least for 50 per cent of the world's demand for energy. That's my opinion."

Trevor Simmons is keen to see those ships coming and going, and not just for the wealth they carry.

"Whenever we have visitors come here, we take them down to the foreshore so that they can see a coal ship come or go, because it's just just like a building floating past. It's just amazing."

FROM the kingdom of coal along the Kooragang shore, the Hunter River's south arm bends and reaches towards the city, about four kilometres downstream.

Along the south-eastern edge of Kooragang is a line of bulk berths. Near an area once known as Rotten Row, where the hulks of ships wrecked or abandoned would slowly decay, materials ranging from fertilisers and sands to alumina for the smelter at Tomago are handled.

The southern tip of Kooragang is called Walsh Point. This is where the Hunter River's south and north arms meet. Before the demands of post-war industry rolled over this place and reshaped the land, it was known as Walsh Island.

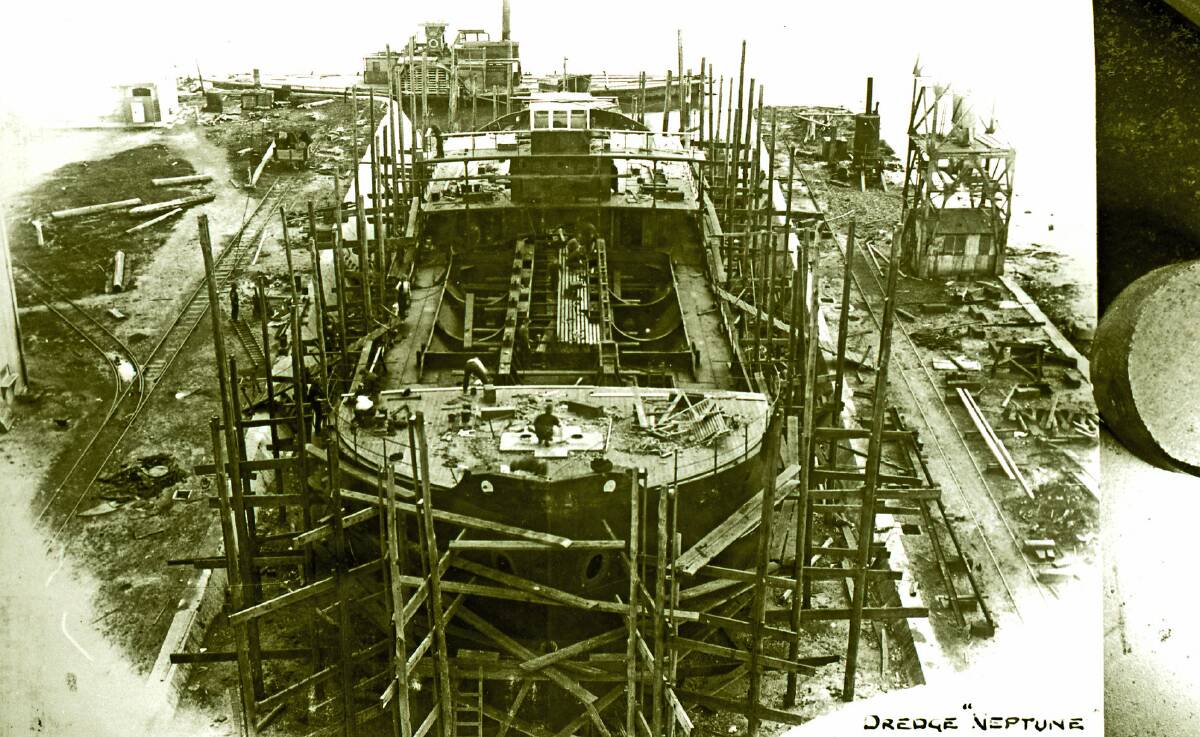

Yet long before it was incorporated into Kooragang, Walsh Island was impacted by human intervention. From the late 19th century, silt from the harbour was used to stabilise the banks along here. Then, in 1913, industry washed up on its shores.

The Walsh Island Dockyard and Engineering Works was established, with ships being built, slipped and repaired here. The first large vehicular ferry for Newcastle, the Mildred, was built on Walsh Island and used to link the city with Stockton.

At one stage, 2500 people worked on Walsh Island. During its two-decade life, the facility built 47 vessels, along with a range of products to keep a nation on the move, from rail carriages to bridges.

The Great Depression took its toll on the dockyard, and it shut in 1933. During World War Two, many of the buildings, along with the facility's floating dock, were transported downstream to become part of the new State Dockyard based around Dyke Point.

Almost 90 years since the Walsh Island works closed, there is little evidence of the dockyard. However, at the end of Walsh Point is a solitary palm tree.

The Canary Island palm is believed to have been in the garden of the manager's residence. As a result, the tree was placed on Port of Newcastle's Heritage Register.

Long-time Stockton Historical Society member Irene Butterworth recalls a tour of the site in the late 1990s and seeing not just the palm but the remains of a stone wall that was believed to be part of a bathing pool in the river.

As plans are debated and developed for using more of Newcastle's portside land, Ms Butterworth hopes the end of Walsh Point remains as open space, with better public access and greater recognition of the area's past, when ships were built and launched here, heading out of the harbour and into the world.

"Don't do anything drastic," Ms Butterworth advises. "And keep the palm tree, whatever you do!"

Next week: Part Eight, and the final instalment, of "Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" takes in Stockton and the journey to the end of the northern breakwater.

Read more of the series:

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" - Part One: Entering the Port.

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" - Part Two: From the 'Dog Beach' to Scratchleys.

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" - Part Three: Along Honeysuckle.

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" - Part Four: Along Wickham's Shore.

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan"- Part Five: From Outrigger Canoes to Silos at Carrington

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan" - Part Six: Around Dyke Point