Almost 30 years ago, Warwickshire county council became the first local authority to close all its children’s homes. It was a hugely controversial move, and a subsequent evaluation questioned its wisdom, but today the council stands by its decision. “It was very ambitious and very visionary,” says Sue Ross, Warwickshire’s head of children’s social care. “Our results have demonstrated that the investment [in alternative services] that we were able to make back then, and which has continued, has paid dividends.”

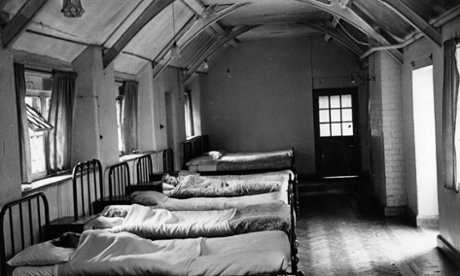

Warwickshire already had relatively few children in residential care when it shut its last homes in 1986. It had boosted fostering during the 1970s, when the national trend had been to expand residential provision, and had moved to professionalise its remaining residential services by turning them into four “children’s centres”.

These centres were staffed by qualified social workers, who also undertook case work, and were used for residential care only with the express, case-by-case consent of the director of social services.

By the mid-1980s, the workers were themselves suggesting that there was no need for the centres and two were shut, with no apparent ill-effects. Peter Smallridge, the then director, says: “We were down to two and I called all the staff in to Shire Hall and told them: ‘This is a big dilemma: what do you want me to do?’ With one exception, they said: ‘It [closure] is what we want.’”

The critical thing, Smallridge says, is that he was backed by the council’s leadership and was allowed to plough the savings from closure back into fostering and other services, including a contract for four places at a local children’s home run by a charity. Even so, many of his peers doubted him.

“It was one of the most innovative things I’ve ever done, but it was quite a risky strategy,” Smallridge says.

“Quite a few director colleagues said that I must be mad and it couldn’t be done. But we were able to do it because Warwickshire was in an almost unique position [in terms of minimal provision] and because we could reinvest the resources. You couldn’t do it now, of course: if you closed your children’s homes, you’d lose the money.”

Warwickshire took the unusual step – almost unthinkable in these times of austerity – of funding a three-year research project on the impact of closure, carried out by the National Children’s Bureau (NCB).

David Berridge, who was then NCB’s research director and is now professor of child and family welfare at the University of Bristol, says he was able to employ a full-time researcher, David Cliffe, who was based at Shire Hall and given free access to all records and staff. “It was very forward-looking of them, says Berridge, “quite remarkable really, but they felt that this was a golden opportunity to ask if we needed residential care, did it serve its purpose and was it value for money.”

The answers, awkwardly for Warwickshire, were broadly “yes”: based on the follow-up of 215 children, the policy change was found to have disadvantaged them, relative to children in care in other parts of the country, by limiting options for their placement, reducing contact with families and friends, and disrupting their education.

A recent assessment of the findings, published in 1992, by childcare writers Robert Shaw and David Lane goes as far as to say: “As a result, [Warwickshire’s] much-vaunted ‘good practice’ resulted in more adverse outcomes for children in care than possibly those of authorities where benign neglect was the order of the day.”

Berridge says: “We still need residential care. It has its challenges, but from all the research studies done there is a clearly identified role for it, particularly in respect of some children with very challenging needs.” Given what we now know about what “benign neglect” has meant for many children in residential care, however, Warwickshire’s radical changes in the 1980s may be looked back on far more kindly.

The county today has about 690 children and young people in care, of whom 28 are in residential homes or schools run by the independent sector. Ross admits that these units can be far away, in the north of England or Wales, but says that they typically offer specialist support. Pointing out that Warwickshire’s Ofsted inspection ratings are consistently “good”, she says firmly: “We’re not looking at any resurrection of our own residential provision.”

Smallridge says: “In the end, our feeling was that, yes, we failed some children, but relatively few, given the numbers that we were dealing with. For most kids, it worked.”

In numbers

1,760

children’s homes in England were on the statutory Ofsted inspection register on 31 March 2014

33%

of local authorities do not have a council-run children’s home

£997.2m

was spent by local authorities on residential care in 2012-13; £616m of that was spent on private-sector provision

Source: DfE children’s homes data pack december 2014. England only

.jpg?w=600)