The late Dutch author and Holocaust survivor Marga Minco once wrote about an empty house in Amsterdam where she and a group of artists and students took refuge towards the end of the second world war. Last month, the house she lived in for decades was squatted by a new generation of the dispossessed. In the Dutch capital’s overpriced, overcrowded housing market, where homes fetch more per square metre on average than they do in London, the squatters, or krakers, are back.

They are the byproduct of a crisis that has spiralled out of control, in which growing anger is justifiably focused on a startling and unsustainable unfairness. The cost of the country’s generous tax breaks for homeowners, who make up more than half of the population, is being borne by hard-working tenants. The return of squatting is a symptom of a public mood that is increasingly furious about the lack of solutions. And with a general election on 29 October, it is an anger that could be politically decisive.

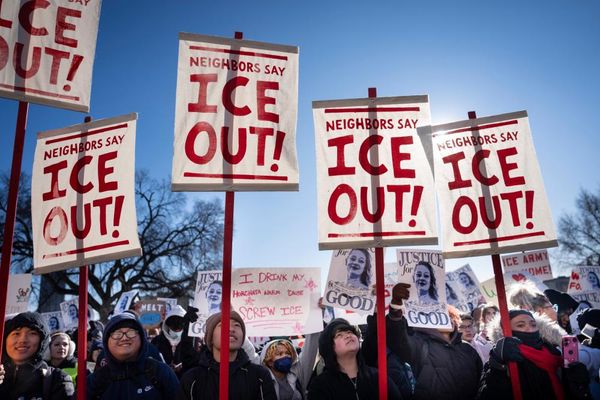

Squatting was made a criminal offence in the Netherlands, partly in response to the Vondelstraat riots of 1980, during which military tanks rolled on to the streets for the first time since the second world war to battle the squatters. But barely a month goes by now without reports of riot police being called in to clear another squat.

In June, riot police emptied one such property in the De Pijp district of Amsterdam, a neighbourhood the tourist guides call bohemian and charming. The squatted premises had previously lain empty for more than two years. A few days after Minco’s former home was squatted, another on the Plantage Kerklaan was cleared by riot police. The confrontational mood should come as no surprise to the authorities when the number of property “millionaires” has never been greater, at the cost of taxpayers and a generation priced out of the housing market.

Take Raoul, 28, whom I spoke to recently. He has a university degree and comes from a home-owning family, but he has nowhere to live so has become a squatter. Like many of his contemporaries, Raoul has qualifications, work experience and is looking for a job, but he knows that even if he finds work, that is no guarantee of an affordable and stable home. Raoul’s take on it may be anecdotal, but he thinks the Dutch squatting movement, which began in the 1960s and had by the 1980s acquired an anarchist tone, is back. “Well, that’s the aim,” he told me. “I think that the same conditions are there. The housing need is as high, perhaps even higher. Kraken is coming back, even though it is now criminalised.”

What is indisputable are the official figures. They show that the Netherlands has a shortage of more than 400,000 properties, with 81,000 people looking for their first home. With prices at their highest ever level and new rent-control laws in place, thousands of private landlords have been exiting the rental market. More properties may be for sale, but at prices that most other Europeans would find absurd, particularly given the subsidence and flooding risks that often come with them. For a lot of young people, the only options are illegal sublets or exploitative room rentals.

Regulations attach strict price controls to rooms in shared houses, making landlords loth to rent, while universities do not offer residential hall spaces. “It’s only getting harder,” says Maaike Krom, chair of the LSVb (Dutch student union). “We heard a story about someone who travelled more than three hours for school because not all studies are available in every city. We don’t realise what the effects are for young people to have that much stress about travelling, finding a house, financial issues … when in five years they need to be part of the economy and build the future.”

So what can be done about it? The broad economic consensus that the Netherlands must phase out its tax breaks for homeowners is a positive. House prices are inflated by the country’s level of mortgage debt to GDP, which is the highest in the EU. The European Commission has called five times for the Netherlands to limit risky housing debt and scrap its mortgage interest relief – most recently in June – alongside the country’s DNB central bank, leading housing experts and economists. But the biggest attitude shift needs to happen among the 57% of Dutch who own a home.

Until these wealthy burghers accept that they have no right to a public subsidy through mortgage tax relief, which costs about €11.2bn a year and increases the tax burden by 1.5 percentage points for even basic rate taxpayers, the Netherlands is looking at a future where the “have nots” have ever less to lose.

Instead of rubbing their hands at their accumulation of paper wealth, they should realise that every €100,000 they “make” on housing is indirectly billed to their children – contributing in Amsterdam to a city in which only the wealthiest internationals can afford to live. Dutch voters have in effect chosen a policy that prices out their own people.

Jona van Loenen, a writer and entrepreneur, sees it as a threat to the Netherlands’ future prosperity when banks invest in mortgages instead of growing companies and owning a house is a better wealth model than starting a business. As he puts it: “We’re creating one of the most perverse incentives a society can have: one where people just sit at home on the sofa instead of actually doing something.”

Of course, the solution to a housing shortage is also to build, and the Netherlands plans to construct nearly 1m homes by 2030 – but this project is already battling against the interests of existing property owners.

The consequences of inaction become clear when you consider that only 4.5% of homes in the Netherlands could be bought by a household on the average income last year, according to figures from the Dutch land registry, Kadaster. Less than a decade ago, in 2017, someone earning the average salary could afford 23% of properties. Prices have almost doubled in the past 10 years.

Since 2014, the Dutch population has also increased by about 1 million through immigration – but this is largely to fill jobs. Despite far-right posturing on asylum, applications dropped last year and this year, the Netherlands has taken below the EU average. The country’s generosity to Ukrainian refugees dramatically increased the pressure on housing, while a number of industries depend on some 850,000 migrant workers, who are often underpaid and, according to the Dutch labour inspectorate, sometimes exploited. Highly skilled “expats” add to housing pressure in places such as Eindhoven and Amsterdam, the UN special rapporteur noted, but Dutch businesses say the country cannot maintain a global tech industry without foreign talent.

At a recent Niet te Koop (“not for sale”) demonstration outside yet another social home earmarked for sale, Jan Leegwater picked up a loudspeaker. “They will ask €600,000 for this because of the potential to extend,” he said. “And if you sell this in a few years, you can net more than if you just work normally … We are suckers, and we are stuck in this system.”

Much of the national fury is misdirected towards asylum seekers and other expatriates. The architects of this crisis are not immigrants – they are the wealthy Dutch homeowners and voters who, year after year, have protected a system that serves their own interests. Unless that mindset shifts, their children’s anger will only grow – and we can expect more krakers to start taking the law into their own hands.

Senay Boztas is a journalist based in Amsterdam