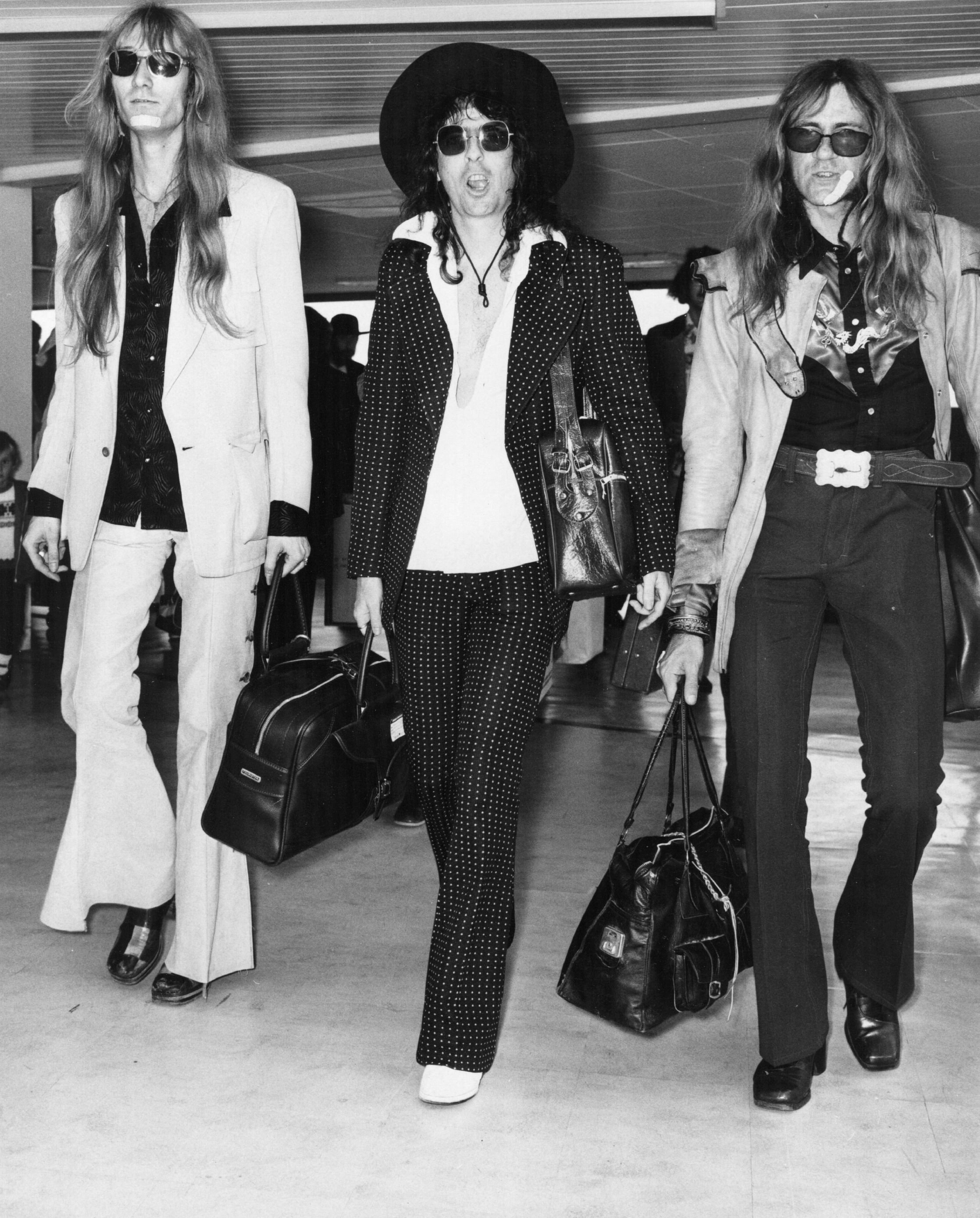

When they were young men, the members of the band called Alice Cooper were a threat to the very fabric of our society. On 28 June 1972, they appeared on Top of the Pops, performing “School’s Out”, and, yes, by that point in glam rock’s evolution, seeing men in candy-coloured Spandex on your TV wasn’t out of the ordinary. But other things seemed all wrong.

The way the drummer, Neal Smith, hunched over his kit like a caveman. The way the two guitarists and the bassist seemed sullen and uncaring. And most of all there was the singer, all in black, with shirt open to the waist, and black gloves – conventional rock star attire from the neck down – but with a face that looked ruined, as if he’d just been let out of a dark cell after a very long time. He wore make-up, but not to make himself look feminine or glamorous. He looked like death.

“We got no class, and we got no principles,” he sneered into the camera. “And we got no innocence/ We can’t even think of a word that rhymes!” Neither Alice Cooper nor the rest of the band of the same name cared one little single bit about being acceptable. And, lo, they were not accepted.

“Top of the Pops has given gratuitous publicity to a record which can only be described as anti-law and order,” said the “morality campaigner” Mary Whitehouse. “Because of this, millions of young people are now imbibing a philosophy of violence and anarchy. This is surely utterly irresponsible in a social climate which grows ever more violent.” Whitehouse demanded the BBC ban the record from Top of the Pops. They didn’t, and Cooper credited her intervention with helping it to No 1.

At least she hadn’t seen the stage show, featuring Cooper being guillotined, executed in an electric chair, tortured and beaten up, though if she had seen the group on the Old Grey Whistle Test in 1971, she’d at least have known about him wrapping himself in a live boa constrictor.

A year later, in the wake of the song “I Love the Dead” – about necrophilia – the Labour MP Leo Abse called for the Home Office to ban Cooper and the band from the UK. “I regard his act as an incitement to infanticide for his sub-teenage audience,” Abse said. “He is deliberately trying to involve these kids in sadomasochism. He is peddling the culture of the concentration camp. Pop is one thing, anthems of necrophilia are another.”

Yet at the same time they were feted by Salvador Dalí – who created a portrait of Cooper’s brain using, among other things, chocolate eclairs, called “First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain”. They influenced bands such as Roxy Music and the New York Dolls, and David Bowie reputedly took The Spiders from Mars to see them to learn about stagecraft. A generation later, and Cooper’s make-up – “corpsepaint” – would become a staple of extreme metal.

They made seven albums in four years, became stars around the world, and were vilified at the same time, and then it was all too much.

“We broke up out of sheer exhaustion,” says Cooper – the man, not the band – over here to play a joint headline show with Judas Priest at the O2 in London, and speaking with his camera off over Zoom (perhaps so the make-upless Alice remains a mystery). He’s articulate and businesslike, and not one bit flaky, a mixture of amused and self-aggrandising.

Cooper went on to become a kind of all-purpose celebrity – appearing on game shows and at pro-am golf tournaments – and became a solo star, first taking the original theatrical concept even further, then riding the hair metal boom with hits such as “Trash” and “Poison”. But he didn’t leave his past behind. “We didn’t divorce so much as we separated. We all went to high school together – we were more friends than we were a band a lot of the time. And we always kept in touch.”

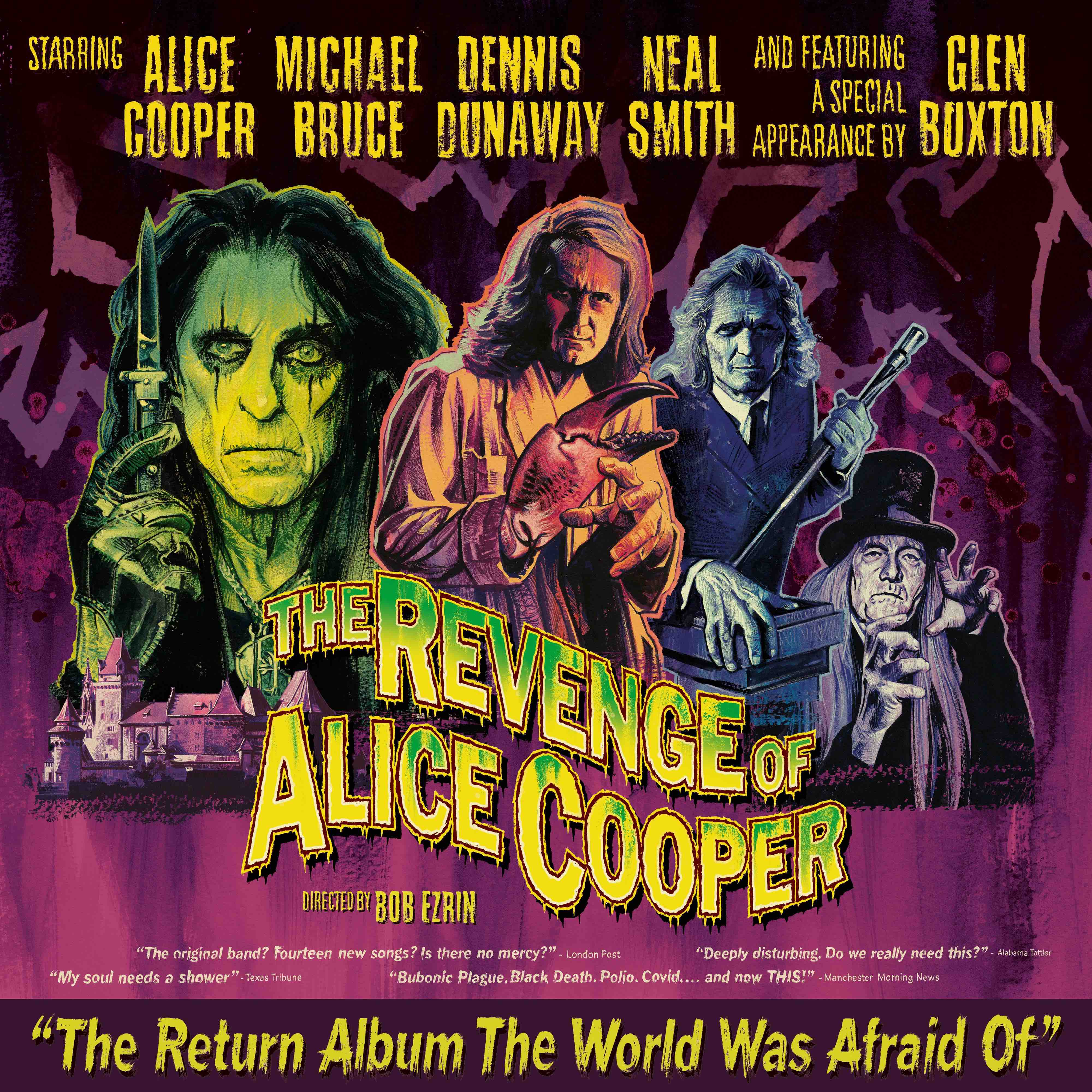

Indeed, the surviving band members – bassist Dennis Dunaway, drummer Neal Smith, and guitarist Michael Bruce – have made appearances on Cooper records in recent years, and joined him on stage. “We’ve been pushing for it for a long time. And this project started in 2021, and there were times in the middle of doing it that we thought maybe it wasn’t going to happen.”

But why should we care? After all, it’s still an old man singing silly horror songs, right? Well, yes – but the original Alice Cooper band were rather more than that. They were one of the great Detroit rock’n’roll bands, alongside the Stooges and the MC5, playing filthy, objectionable, perverse high-energy rock’n’roll at a time when the Laurel Canyon singer-songwriters were trying to sell America a dream of thoughtful domesticity.

They didn’t come from Detroit, but from Phoenix, via a couple of years in Los Angeles. They arrived in Detroit – Cooper’s home before Phoenix – to play a festival, where they saw the Detroit bands blazing through their sets, Iggy covered in peanut butter, the MC5 playing like it was a soul revue, and realised they were in the right place. They simply stayed.

Even before they had guillotines on stage though, they brought chaos. At one show in Phoenix they opened for Blue Cheer, who claimed to be the loudest band in the world, and they were told by witnesses they were louder. “At that particular gig, Neal had his leg in a cast because Alice had shot him with a rifle,” Dunaway says. “But that’s a whole other chapter.”

No, it really isn’t. Please elaborate.

“It was early 1968,” Smith says. “We’d come back from California to rest up and make some money – we made a lot more when we played our hometown. We were there for two, three months, and you know, you get bored at night. So we borrowed one of Dennis’s dad’s or brother’s .22 rifles. You drive into the desert at night, put the headlights on, jackrabbits’ll just pop up.”

“They were layin’ on the hood of the car,” Dunaway says.

“We shot one, I thought I hit it so I ran off to see.,” Smith says. “But the rabbit got away – we never did hit a rabbit, for all you animal lovers out there – and a gun goes off and, boom, I feel the pain in my left inside ankle bone.” Hospital doctors told him it would cause more damage to have the bullet removed than to leave it, so he was discharged with a cast. “Later on, I cut it out with a hunting knife, in Topanga Canyon,” Smith says, as if that were the obvious thing to do. “It didn’t hurt.”

The pair of them no longer look like a threat to society, so much as a pair of old hippies reminiscing on a front porch: if you saw them, you would assume they were men who never got around to cutting their hair, rather than the most dangerous men in the world. The clothes aren’t neon now – they are the dun-coloured casual clothes of the ageing everyman – and they banter with the air of men long used to pondering ridiculousness. Dunaway, in sunglasses indoors, is more reticent at first, but they speak with the familiarity of years of friendship, interrupting and laughing at each other.

But back when they were a scourge, at least the rabbits were spared, unlike the chicken Cooper threw into the crowd at the Toronto Pop Festival in 1969, where it was ripped to shreds. It’s often claimed the chicken had been thrown on stage, but guitarist Michael Bruce later admitted they brought the chicken themselves, as they did to many shows. And, yes, it probably wasn’t the only one to die.

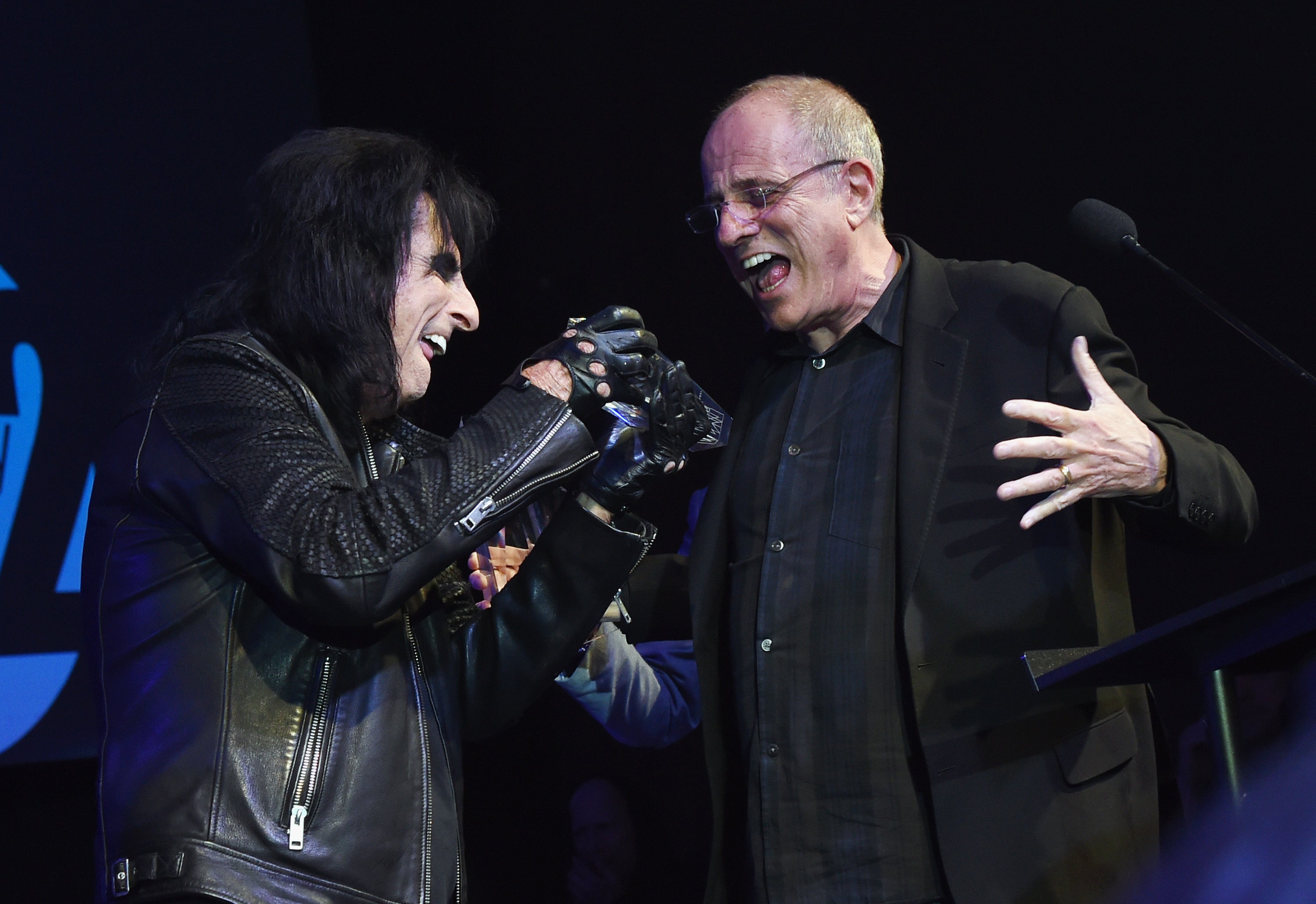

After two misfiring records, what saved Alice Cooper was meeting a 21-year-old Jewish hippy from Toronto called Bob Ezrin. They had approached the hit producer Jack Richardson to produce them, but he wasn’t interested and sent Ezrin, his underling, to give them the elbow.

“My job was to go to Max’s Kansas City on 9 September 1970, for a midnight show and get rid of Alice Cooper,” says Ezrin, who has produced the new album. “But I saw this show that was otherworldly. Max’s Kansas City that night was like a Hieronymus Bosch painting – everything and everyone in there was from the netherworld. It was like Night of the Living Dead. The group comes out in crazy spaceman costumes, with Alice in a ripped leotard and thigh-high boots. I couldn’t keep my eyes off the stage, and I couldn’t believe the energy in the room.”

Instead of getting rid of Cooper, Ezrin was sent to Michigan to produce them, his first ever production job.

“He was just a kid like us,” Cooper says. “He was absolutely in the deepest water. We were all drowning and he found a way to make it work. We were all fed up of each other, but for some reason we listened to Bob. We never listened to any producer. But Bob Ezrin took what we had and put it in a form that could be played on the radio.”

“He taught us how to take a song apart and get rid of all the excess,” Dunaway says (Alice Cooper were prone to multisectional epics in which the tune got lost). By trimming off the fat, Ezrin gave Alice Cooper what they needed, a hit single: “I’m Eighteen”.

“He heard us jamming, and he said, ‘What is that? I think that’s a hit. Just keep dumbing it down. Dumb it down. Dumb it down,’” Cooper recalls.

“I brought clarity,” Ezrin says. “I also think I’m a tinkerer by nature: I’m the kid who took apart the family piano and then had to put it back together before anyone had discovered what I’d done.”

After “I’m Eighteen” was a hit in 1971, Alice Cooper released five albums in three years, the first four produced by Ezrin (though Richardson got a courtesy credit on the first), and with each successive record they pushed the boundaries of taste ever further. The 1973 album Billion Dollar Babies – an astonishing, sometimes symphonic rock album, was with one breath satirising the presidential race (“Elected”) and then offering an orchestral hymn to necrophilia, “I Love the Dead”, as it veered between social commentary (“Generation Landslide”) and the genuinely creepy orchestral ballad “Sick Things”. Did no one ever say, you know what, this one might be pushing it a bit too far?

“No!” Dunaway protests. “Do you want to pull in the reins? No. We had censors breathing down our necks every inch of the way. We’d show up at a gig and the fire department would be there, and the police, and the Humane Society, all telling us we can’t play there. But we would keep going right up to the edge of what you were allowed to do, and then stick our toe across and push the boundary ever so slightly.”

Given success, the band pursued it without stopping, fearing it was transient. But incessant recording and touring took its toll. After 1974’s Muscle of Love, they realised they needed to stop – and they simply never got back together.

It seems like a situation where if someone had told them to take six months off, they might not have had to have 50 years off. “You’re not wrong,” Ezrin says. “Everyone was worn down. The one person who wasn’t worn down was Alice, because Alice is bionic.”

Cooper, of course, went on to be many things. Like the late Ozzy Osbourne with his “Prince of Darkness” image, the “Godfather of Shock Rock” would forge a long, successful solo career, although, also like Ozzy, he would always be associated with his gruesome past. In a Sounds interview in 1975, which begins “His Satanic Majesty lay quietly on the couch…” Cooper laughed it off. “The parents take it seriously but the kids go, ‘Aaw, come on!’” he told the interviewer. “Going to see our show is like going to see Christopher Lee in The Vampire; it’s a movie. People don’t go home and bite their wives in the throat afterwards.” The reporter responded in kind, describing how the band had “perpetrated their evil designs through long-playing records which proved addictive to souls unfortunate enough to overhear them”.

Cooper and I talk just hours before the death of Ozzy is announced, and the parallels between the two men’s careers are clear, except in the respect that Cooper hasn’t drunk for more than 40 years. And when Cooper performs at the O2 at the end of the week, he encores with a version of Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid”, wearing an Ozzy T-shirt. It feels like an apt tribute from one vaudevillian to another.

Ezrin, meanwhile, went on to become one of the superstar producers of the 1970s, working on the likes of Berlin by Lou Reed, Destroyer by Kiss and The Wall by Pink Floyd. For the rest of the Cooper band, it wasn’t so great, and lead guitarist Glen Buxton died in 1997. But now everything has come full circle, and everyone concerned sounds genuinely delighted. “I think there was something about Alice Cooper that people connected with,” Cooper says. “We were the underdogs. But when we made records, those records were really coming out of us.”

And it is certainly a surprise when one surveys the remains of the Detroit rock scene and realises the two people still working constantly are the two who seemed most out of control – Alice and Iggy Pop. “It’s a matter of: are you a lifer, or are you not a lifer?” Cooper says. “Pete Townshend? Lifer. He’s going to do this ’til he can’t do it any more, ’til his fingers are bleeding. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, they are going to do it ’til they can’t do it any more. I’m not at their level, but I will keep doing it until I can’t do it anymore.”

‘The Revenge of Alice Cooper’, the first album from the original Alice Cooper band in over 50 years, is out now on earMUSIC

Ozzy Osbourne flung open hell’s musical gates – and changed the world

Live 8 – 20 years on: how the Pink Floyd reunion topped a miraculous line-up

Robin Williams reportedly wanted to buy a comedy club to impress David Bowie

The Maccabees on reuniting: ‘There were years when it was like a stranger messaging’

Art snobs won’t find much to love at Radiohead and Stanley Donwood’s exhibition