“You have to understand. I’m a nun. I took a vow of chastity. To stand in court and say I was raped felt like I was the sinner,” said Sister Ruth*, almost in a whisper. “I felt unworthy of God.”

We spent most of the hour in silence. The group of nuns sat in a row, scepticism heavy in the air. At first, they didn’t reveal who among them had accused a bishop of rape.

Outside, the light drizzle and the afternoon humidity lulled the two policemen into a slumber. This was in October 2024 – our first meeting.

After tea, when the awkward conversation drew to a close, one of the nuns came forward, smiling as she took my hand. At 50, her skin had begun to wrinkle. She led me to a door that opened onto a garden. I admired the colours of bougainvillaea in bloom.

“When the police came to take our statements, they took cuttings of the bougainvillaea and planted them outside their station. Apparently, they’ve named the plants after each of us,” she said, referring to the case for the first time.

“Yes, I’m the one.”

We stood there, not taking our eyes off the flowers, until she broke the silence again. “I have tried not to think about it for a long time now,” Ruth said very softly.

Behind us stood the three-storeyed, 28-room convent. We were surrounded by the six acres of land that belong to the diocese of Jalandhar under the Catholic Church.

Inside, four nuns – Ruth, Alphy, Ancitta, and Anupama – move swiftly along the corridors. Their strides are short and purposeful. They go from chore to chore, room to room, knowing fully well that they are only going in circles.

During the day, after prayer, food is cooked, the chapel is cleaned, and the chickens are fed. Eggs, chillies, and vegetables are collected, and tamarind is peeled. The electricity goes off multiple times. When the day lulls, they sometimes do embroidery, moving the clock along with their needles.

At night, the building creaks in the wind. The sound of crickets is louder than the voices in one’s head, which is good.

Sometimes the nuns stop each other in the corridors. The desolate building echoes with their words, laughter, and even their arguments. Disagreements about a chicken’s behaviour or the spiciness of a dish can turn lengthy. Seemingly banal matters often gain presidential importance. But this is intentional.

Every single morning – in that private moment when one has just woken up and the world hasn’t come into focus yet – each of them quietly resolves to attend to the ordinary, argue about the mundane and laugh at the inevitable.

That is the only way to live in the same building where Sister Ruth accused Franco Mulakkal, the former Bishop of Jalandhar diocese, of raping her multiple times.

The violence allegedly took place between 2014 and 2016. Ruth filed a police complaint in 2018. This was the very first time in India that a nun had filed a rape case against a bishop.

Franco was a powerful man. At the age of 44, he had been chosen by the pope to head the Jalandhar diocese of the Latin Catholic Church. This gave him direct spiritual and administrative powers over a congregation that spanned multiple states, several religious orders, and over a hundred convents, including Ruth’s.

This fiduciary relationship is central to the legal and moral dimensions of the case and its aftermath.

The trial lasted two years. In 2022, Franco was acquitted.

Over 60 percent of the 6 million Christians in Kerala are Catholic, which is why this story is not just about sexual abuse. It is a case that grabbed an entire community’s faith by its neck.

After the verdict, the case quickly slid off the news cycle. But life, as it does, continued, and the story took a turn that the nuns never expected.

The Church began arm-twisting and steadily exhausting them financially, emotionally, and spiritually. The hierarchy wanted them out of nunhood.

At the beginning of this case, Ruth lived with five ally nuns in the convent. By the end of August 2025, only two remained.

Throughout the investigation, trial, judgement, and the years after, Ruth has never spoken out.

Nearly 11 years since she was allegedly raped, Ruth is now ready to tell her story.

Speaking to a journalist was never her first choice. In our 10 months of conversations, she often insisted that talking to me was not a mere act of strength but a last resort.

“The only reason I’m talking is because I want people to know that we have not gone anywhere. We are still here,” Ruth said.

Forty minutes away from her convent is the retreat centre where Franco now lives. In 2023, he met the late Pope Francis and resigned. He now spends his time conducting prayers and counselling women and children. He conducts regular retreat and prayer sessions across Kerala.

When I first went to him with my questions, he said he could not speak to me as the case is under appeal at the Kerala High Court.

But later he agreed.

“I am a diamond,” he declared. “You can put me in dirty water or on Queen Victoria’s crown, my value doesn’t change.”

Franco still speaks as if he is at the pulpit rather than a man in a small room with an audience of one.

He may not admit it, but Ruth’s allegations did force him into exile.

Franco’s acquittal sentenced Ruth to indefinite and absolute isolation.

But she has faith.

“Imagine if the whole system is one massive rock. I know I’m not capable of splitting it in two, but I can definitely scar it with a nail.”

This is her story.

Chapter 1: Leap of faith

Elegantly dressed women, clean surfaces, and gentle, fatherly men – this is how the Church imprinted itself on 8-year-old Ruth’s mind.

Until she joined the convent, Ruth was the shy one in her family of four sisters and a brother. Her father was a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) officer, and her mother was a homemaker.

Ruth recalled her childhood as sunny and carefree, wrapped in her mother’s love and the warmth of her siblings.

She spent her days detesting school and trailing after her boisterous elder sister. “I did not like confronting people. But my sister argued with boys and had lots of friends. I was the one carrying both our school bags, running after her,” Ruth said, bursting into a laugh.

It was at the local church where she crept out of her shell. She danced, sang, and prayed under the guidance of the nuns.

Given her reserved ways, everyone in her neighbourhood told her mother, “Oh ee kochu Sister aavueullo.” This roughly translates to “Oh, this child is going to become a nun.”

By the time she reached high school, Ruth told everyone that she wanted to be a nun. It was not a carefully considered answer but one that seemed to silence the pressure of further studies.

When she turned 15, life took a sudden turn. Her mother, the centre of her universe, was diagnosed with cancer. Almost overnight, Ruth and her sister became caregivers. Within two years of the diagnosis, their mother passed away.

It has been 35 years since then. Her voice still trembles when speaking of her mother. “I’m glad she didn’t live to witness my life,” she said.

To Ruth, her life exists in two parts – before Amma and after Amma.

Young Ruth was angry with God. “I used to say, ‘God doesn’t have eyes. How could He take away my mother when we were just kids? Does God really listen when we pray?‘” she recalled.

Months after her mother’s death, her cousin, who was a priest, visited and saw how inconsolable Ruth was. He offered to take her to Punjab with him. In 1993, she left for Jalandhar.

Punjab was in a period of cautious transition.

The Sikh insurgency demanding a separate Khalistani state had largely subsided, and the region was returning to normalcy. Democratic elections had reaffirmed civilian governance. Yet, violence lingered in pockets. Security operations were ongoing. A devastating flood had triggered a humanitarian crisis.

But Ruth was unaware of any of this. For her, it was simply her first train journey to a place where she would experience her first winter.

In Jalandhar, she stayed with her family before moving into a convent. She followed the nuns to church and to villages where they taught at schools.

The quiet, regimented life of the convent steadied her. In time, Ruth was more convinced that she wanted to be a nun.

After five years of religious training, she donned a habit, adopted a new name and was ready for the final and absolute step in her spiritual journey.

In the Catholic faith, nuns are considered to be symbolically married to Christ. They remain celibate and entirely devoted to Him and the Church.

To seal this commitment, in 1999, Ruth took the three sacred vows that were to govern the rest of her life: chastity, poverty, and obedience.

What she did not know then was how deeply these vows would come to define – and test – her in ways she could never imagine.

Her time, her days, her entire life had now been handed over to the Church.

For a nun, convent life is laborious. Many young women often struggle with adjusting to this strict life. They wake up at dawn, pray, clean, cook, pray, go to work, have lunch, rest, pray, clean, cook, and sleep. If a priest or bishop visits, they run on his time. Life is regimented and monotonous.

But Ruth slipped into it with ease. It was what she needed. And in 2004, she was appointed the mother superior of the entire Missionaries of Jesus congregation – a small and growing order.

The Jalandhar diocese oversees multiple congregations across 14 districts in Punjab, three in Himachal Pradesh, and a few in Kerala. In June 2013, they reassigned Ruth to a convent within the Missionaries of Jesus congregation in Kuravilangad, a town in the northern part of Kottayam.

Here she took charge as the local mother superior of the St Francis Mission home convent.

Little did she know that this place – meant to be quiet, familiar, and comforting – would slowly churn into something darker.

Chapter 2: The Bishop’s reach

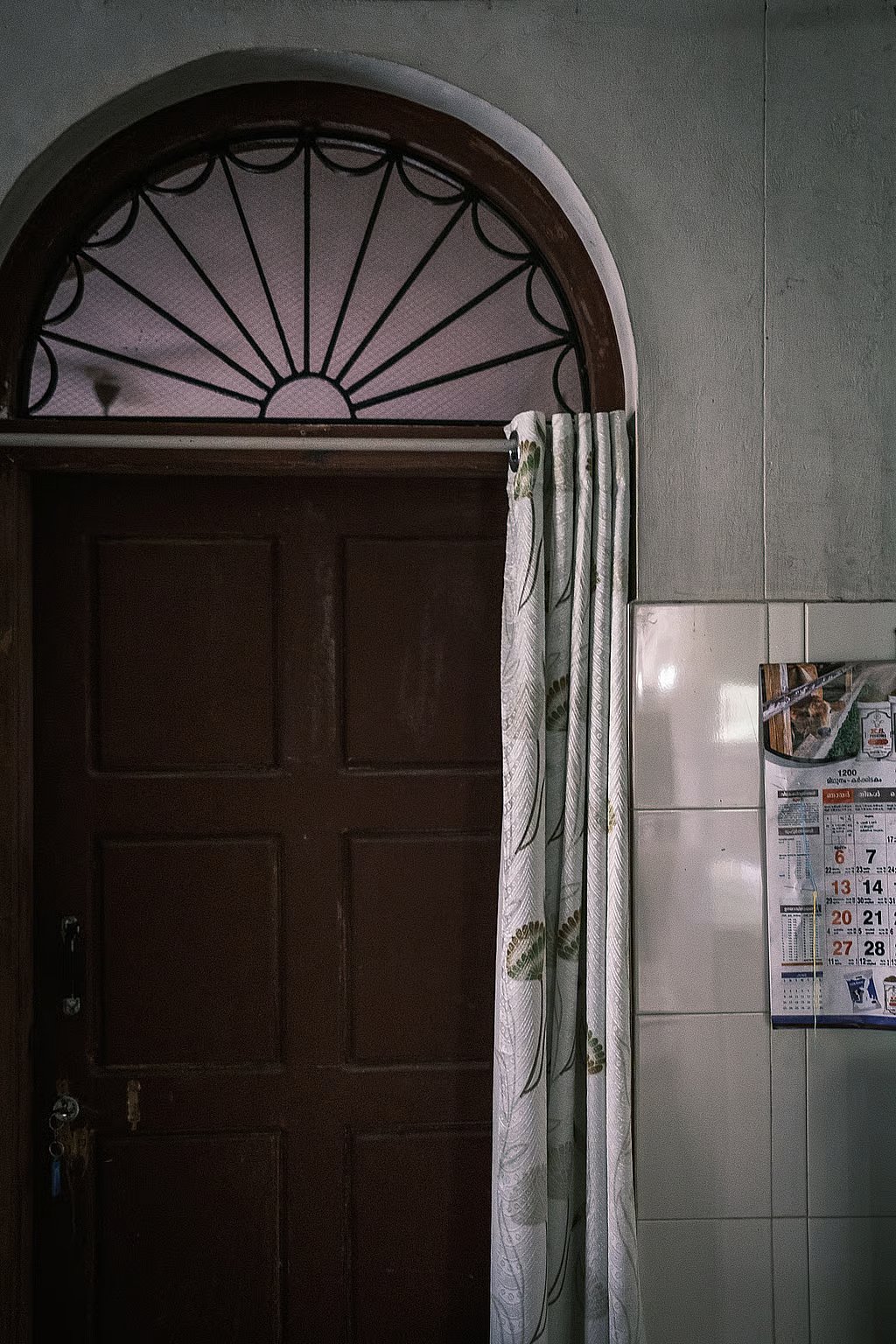

On either side of the muddy pathway that leads to the convent, the coastal soil bursts with greenery – wild, untamed, and abundant. Some of it is tended to by the nuns, some by nature.

At the end of that pathway, behind a rusty iron gate, stands the convent.

Inside, the walls smell like they’ve never had a chance to recover from the relentless Kerala monsoons. Today, the moss-covered convent feels desolate.

This was not always the case.

When Ruth first arrived in July 2013, the convent was lively, serving both as an old age home and a youth hostel. She, along with two other nuns, managed the mission.

The same year, nearly 3,000 kilometres away in Punjab, Franco was brimming with pride. He had just been chosen by Pope Francis as the third Bishop of the Jalandhar diocese.

When I spoke with Franco, each conversation lasted for hours. He enthusiastically recalled his childhood, his visions, his case, time in jail, and life after the verdict.

“My vision of missionary work is to organise poor people, fight for justice, get beaten up, get arrested, and go to jail. Once released, I will again organise a massive crowd; the police will shoot, and I will die in action. This is my dream, to be a martyr,” he said.

He is a good storyteller. Sometimes his voice drops to a whisper. Sometimes, his hands raised, his voice booms across the room. He even stops to question his audience, which is usually just me, making sure I’m listening.

His father’s dream, he said, was to see him become a professor. While growing up, Franco had briefly wanted to join the army. But, Franco says, he was quickly swayed by Catholic literature.

He was 15 years old when the decision to enter the clergy was sealed. Not by him but by Christ Himself. One day, he said, after Mass, while he was still kneeling, “I heard Jesus. He told me, ‘I want you to be my priest.’”

After training in Jalandhar, he went to Rome for his theological studies. “I wanted to study about cloning and the Catholic stand on it.” But Franco was advised to familiarise himself with Sikhism.

He did his thesis on Guru Nanak’s moral teachings within the context of Christianity.

It paid off. Back in India, he became a consultant to the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, a Vatican body that advises the pope on relations with other faiths.

The bishop’s seat of Jalandhar is no ordinary position. It is regarded as one of the most influential roles within the Roman Catholic Church in India. For 44-year-old Franco, his journey toward power was gaining direction.

In August 2013, when he was made the Bishop of Jalandhar, nearly 25,000 people, including 700 nuns, 400 priests, 27 bishops, and a cardinal, attended his coronation ceremony.

The diocese manages over 150 churches with nearly 120 priests, along with 50 schools, a college, and 10 hospitals spread across three states.

Franco worked fast. He immersed himself in social work, started a widows’ fund called ’Vidhwa Pension’, and set up a system to distribute gifts during Christmas to the poor.

He started a transport and construction company, both of which were entrusted with contracts from the diocese.

He rose rapidly through the region’s social and political circles, earning a reputation as a key figure in fostering interfaith confidence. His influence was not limited to Punjab. It extended to the entire Missionaries of Jesus congregation and its units in Kerala. Ruth’s convent fell under his control.

In November 2013, just three months after his appointment, Franco contacted Ruth for the first time over a phone call. He ordered a halt to an ongoing kitchen renovation at the convent, even though building materials had already been purchased.

Chapter 3: Room number 20

It was only after my third visit that we began addressing the alleged rapes. Each time the conversation edged in that direction, Ruth would fall silent.

“I don’t want to make you repeat things,” I gently told her.

“It’s not easy,” Ruth said, and explained how “deeply sad” she felt even just to think of it all.

For details, she requested I rely on the legal documents. Ruth had recounted everything to her prosecution team and the court. Her testimony is preserved in the 289-page judgement.

What follows is a reconstruction drawn from that. There will be no graphic retelling of the acts of violence she described. The alleged rapes, while central, are only a flashpoint in a much larger story.

On May 5, 2014, around 10 pm, the document notes, Franco drove through the convent gates in his BMW. When a bishop visits a convent, it is customary for nuns to serve and attend to his every need. This ‘attending to’ often includes kneeling before the clergyman, kissing his ring, ironing his clothes, preparing meals to his preference, and more.

That night, he was to sleep in room number 20, a small, somewhat isolated room at the edge of the convent. In preparation for his visit, it had been cleaned thoroughly two or three times.

Shortly after arriving, Franco asked Ruth to iron his cassock. After the other nuns had retired for the night, she knocked on his door with the freshly pressed garment.

He asked to see the paperwork related to the ongoing kitchen renovation. At 10.45 pm, she returned with the papers and knocked again. This time, she was allowed inside.

“As soon as she stepped into the room with the papers, the accused suddenly locked the door from inside and caught hold of her. He pulled her to a cot …”

The document goes on.

“She was numb with terror. Her voice did not come out. She was trembling with fear. She asked the bishop what he was doing. The accused replied that it was he who sanctioned the kitchen work and held her tight. He forced her to lie down on the bed …”

From there, the judgement goes on to recount – in graphic detail – Ruth’s description of the first alleged rape.

The prosecution states: “Sister Ruth swears that the bishop was like God to her. She had placed him in her father’s place. She didn’t expect such a person to abuse her sexually.”

According to her lawyers, after the alleged rape, Ruth “swiftly took her veil and dress from the floor and tried to get out of the room. While she was moving out, the accused angrily told her that if the incident were made public, she would face the consequence. [sic]”

Franco also warned her that he would stop the payment for the kitchen renovation.

The next day was Ruth’s nephew’s First Holy Communion, a significant event for her family. Franco was the chief priest of the ceremony.

Ruth had no choice but to travel with Franco in his car to the event and sit through it.

Her widowed sister had only just begun to rebuild her life, so Ruth chose not to tell her about the night before.

When they returned to the convent, Franco threatened her again, ordering her to “come to his room without much drama.” She knew what awaited her behind that door. But Ruth feared that if she didn’t comply, it would bring his wrath upon her younger sister, also a nun in the same congregation, or on the nuns she lived with.

“With no choice left,” she told her lawyers, she went to Franco’s room around 11.30 pm and knocked. He opened the door, let her in, and slammed it shut behind her.

“She was forcibly made to lie on the bed,” the prosecution said, before graphically describing this instance of the alleged rape.

That night, Ruth reported being in particularly severe pain. According to her, after that visit, Franco began calling repeatedly, asking if she had told anyone or was scared. He even sent her sexually explicit messages, she said.

Ruth told her lawyers that on July 11, 2014, during the alleged rape, she “pleaded” with him “not to hurt her anymore. She said that she would kill herself. But the accused laughed at her.”

On another occasion, when he summoned her, she refused to comply. He then called her on the phone and threatened her. She eventually gave in, “for she knew that the accused would not even hesitate to kill her.”

Between 2014 and 2016, Ruth alleges that she was raped multiple times.

One evening, while I was at the convent, she and I were sitting in a small room filled with suitcases, a table, and stacks of cloth. The room had little ventilation and almost no sunlight. We were sipping tea, and she was telling me about how snakes often found their way into this side of the building.

At some point, I asked her which room was number 20. She looked up at me and said, “This one. We are sitting in the same room right now.”

Chapter 4: Confessions

In December 2014, seven months after the alleged rapes had begun, Sister Lissy Vadakkel visited the convent for Christmas.

Lissy is Ruth’s spiritual mother, someone who is chosen to mentor and support a younger nun. The two had known each other for over 16 years.

Between 2014 and September 2016, Ruth did not tell any of the nuns living in the same convent. They were younger and looked up to her like a mother.

“The constant struggle to carry out my responsibilities, to act like nothing had happened, that difficulty cannot be explained,” she said.

If Ruth felt fear, confusion, or pain, all of it stood entirely eclipsed by one emotion – shame.

The years of training as a nun ensured that shame had been well written into her body. At no point in the two allegedly violent years did she feel like a victim or a survivor. Instead, bound by her vow of chastity and shaped by an institution that equated ‘purity’ with worthiness, she felt she had transgressed into a sinner.

Unable to hold on to her suffering all by herself, Ruth confided in Lissy about Franco.

The senior nun was not entirely shocked.

“Nuns often speak to me personally. I am used to hearing of such incidents about the Church. I usually try to guide them on how to overcome it,” she told me. But to hear that it had happened to her own spiritual daughter caused her immense pain.

Both nuns wept. Along with grief came fear.

Lissy immediately told Ruth that she must not speak of the alleged violence to anyone else.

“My child, it’s a Father you’re accusing. The most we can do now is pray that the devil in him goes away,” Ruth recalled Lissy saying.

A nun is trained not to “reveal such matters to the outside world,” said Lissy when I asked her why it was so important to keep this a secret.

Ruth also told Lissy that ever since her vow of chastity had been “broken,” she had been struggling to find the will to live. From that moment on until today, Lissy’s singular purpose has been to ensure Ruth “stays alive.”

The weight of this shame led Ruth to the confession booth.

In Catholic practice, a confession is also called the sacrament of reconciliation. It is a journey from remorse to penance. The first demand of a confession is absolute and total guilt. Once an individual has confessed their ‘sins’, the priest, acting in persona Christi (in the person of Christ), offers forgiveness.

In the context of sexual violence, confession takes on a deeply complicated dimension. It forced Ruth to frame her experience through the lens of moral failure.

In response, the priests she confessed to indirectly blamed her for the alleged violence. “They told me, ‘You should walk decently’ or ‘You must have presented yourself to him in that way,’” she said.

“Not one person told you that it’s not your fault?” I asked her.

“Yes, one did.”

In September 2016, Ruth, along with Sisters Neena, Ancitta, and Anupama, went to a spiritual retreat in Attappadi, about 200 kilometres away.

Here, she confessed to another priest.

“For the first time, a priest told me to resist it,” said Ruth. “I asked him, ‘If it becomes public, where will I go?’”

By then her father had passed away, and she did not want to burden her siblings. There was little space for Ruth at home.

But more than anything, she was unwilling to give up on the choice she had made as a young girl.

For a nun in Kerala, the indignity of renouncing the convent begins within language. There is a taunt in Malayalam – maddam chaadiya Sister – which translates to ‘the Sister who jumped the convent’. It does not afford an individual the dignity inherent in words like ‘resigned’ or even ‘left’.

In the 1970s, when Ruth was a child, she had heard her neighbours use this phrase to describe another woman. In fact, every relative of the woman was defined by her decision to leave the convent. “That’s why this whole exercise is so humiliating.”

If language plays any role in defining one’s sense of belonging, in Ruth’s case, it has ensured both exile and captivity at once.

The priest offered Ruth a solution. “He told me, ‘If you ever need to leave, you can come here,’” she said and added, “But he was clear that I must stand firm against the abuse.”

It was as if Ruth, who had been holding her breath, could finally breathe a little. “Sometimes all it takes is one single person,” she said.

Since she made an anonymous confession, to date, she does not know the identity of the priest who told her this. He exists to her only as a voice of courage.

The other nuns asked her about her particularly long confession. Finally, she broke down and told them about the alleged abuse.

“None of us had any idea that this was happening,” Neena told me.

Shocked and in pain, they assured Ruth that if Franco were to return to the convent, they would make sure she was safe. “We told her, ‘In our own ways, we will protect you,’” Neena recalled.

Chapter 5: House of cards

On October 4, 2016, Ruth, along with the other nuns, called Franco. In what became their first act of collective defiance, she told him that he could no longer visit the convent, say the legal documents.

The words of one priest and the steadfast support of her ally nuns made Ruth feel as if “her arms were held up” and her “lifeless body” was “being moved forward.”

Within a few weeks, she received a call from Jalandhar. Her cousin Jaya had filed a complaint with the Catholic Church. Ruth was accused of having an affair with Jaya’s husband.

In February 2017, Ruth was removed from her post. The order, she was told, had come directly from Franco. “That was the very first reaction of the congregation to this entire thing,” she said.

Another nun named Sister Tincy took over as the mother superior. Now, Franco was no longer obligated to inform Ruth if he wanted to visit. Neena recalled that Tincy was very vocal about being sent by Franco himself.

Fear overrode every other emotion.

Ruth decided to leave nunhood. With her, several other nuns also resolved to exit.

In preparation for her to go home, she told her family of the alleged sexual assaults. But they dissuaded her from returning, as they believed the neighbourhood would mock them. They urged her to keep the matter private to protect the “reputation of the Church.”

With nowhere left to go, the nuns decided they would ensure Franco was held accountable.

What had come to light could no longer be turned away from. They wanted an internal investigation.

This is when she started writing letters to authorities in the Catholic Church. In July 2017, Ruth first spoke to local priests, then to two bishops – Bishop Mar Joseph Kallarangatt and Bishop Sebastian Vadakkel – and to Cardinal Mar George Alencherry, who also served as the Major Archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church.

Cardinals are the highest-ranking clergy members below the pope and are considered his closest advisors.

Soon, word reached Franco. The retaliation was swift.

Neena was threatened with disqualification from her exams. Anupama was transferred and demoted. The Jalandhar diocese filed a police complaint alleging that Ruth and Anupama had threatened suicide. Ruth was also accused of physically assaulting a nun.

A panel was set up to investigate her.

She started to panic.

In 2018, she sent a handwritten letter to the highest authority of the Catholic Church in India, Archbishop Giambattista Diquattro, the Apostolic Nuncio of India and Nepal.

A Nuncio is the Vatican’s diplomatic ambassador.

During the trial, Bishop Kurian Valiyakandathil of the Bhagalpur diocese told the court that he personally handed over Ruth’s letter to the nuncio. When the nuncio opened the letter, Kurian said, he uttered the word “rape” and then closed the file with the remark, “This is a serious matter.”

Ruth also wrote letters to officials in the Vatican office – Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Cardinal Luis Tagle, the State Secretary of the Catholic Church, and Pope Francis himself.

In her efforts to report the matter, Ruth had turned to every single authority she could. In total, she had reached out to over 20 clergy members and made 14 formal attempts to report it.

She was met with silence.

With time, Ruth realised that several senior Church officials she had approached faced charges of their own.

Cardinal Alencherry, accused in a high-profile land scam, resigned in 2023 citing health reasons.

The Apostolic Nuncio Giambattista Diquattro was transferred to Brazil in 2020 amid accusations from Indian Catholic groups of shielding corrupt bishops.

Cardinal Marc Ouellet was accused of sexual misconduct in 2022 and retired in 2023. The next year, a French court convicted him of “serious misconduct” for expelling a nun without cause.

When I reached out to each of these officials, only Ouellet’s publicist responded, saying that the former cardinal was unaware of the case.

One evening, as we sat reading some of Ruth’s letters and emails to the Church, her eyes brimmed with tears. I asked her if she was surprised by the silence.

My question made her laugh.

“You know, I was so naive. I thought I would get a reply the very next day. I truly believed that they were all ‘God’s people’. That they would surely take action; they would stop it,” she said and added, “But everything turned to ashes.”

In June 2018, the Jalandhar diocese filed a police complaint against Ruth, her brother, and family members of the five nuns, accusing them of threatening to kill Franco.

By this time, Ruth had informed her brother about the alleged rapes.

Franco's complaint was handed over to the Kottayam police. Ruth then told her brother that it was time to tell the police.

With no one left to turn to within the Catholic Church, she filed a case.

Franco was booked for wrongful confinement, repeated rape by a person in authority, unnatural offences, and criminal intimidation.

“We were pushed and pushed to a corner… with no other option left but to speak up,” Ruth said. To date, she would have rather had this sorted out within the Church.

“I just wanted him to leave me alone,” she said.

After the police complaint, the case slipped beyond the authority of the Catholic Church, and the news of Ruth’s complaint spread.

Chapter 6: Silent siege

Despite the gravity of the allegations, Franco remained free for over 80 days.

On September 8, 2018, the five ally nuns began a sit-in protest in Kochi. They demanded his immediate arrest.

A group called Save Our Sisters (SOS) was formed, bringing together Church allies and activists. Over the days, the demonstration grew, both in numbers and urgency.

Father Dominic Pathiala, a Capuchin Priest, was one of the strongest voices. “The first Bishop of Jalandhar was a saint. But now, in the place where a saint once sat, there sits a devil,” he said.

Ruth’s case was unfolding during a pivotal moment – both in Kerala and globally.

In 2017, the sexual assault of a top female actor had triggered a feminist reckoning in Kerala much before the Weinstein revelations broke in Hollywood. By 2018, the global #MeToo movement had gained fire, and the Catholic Church was facing allegations of clergy abuse, which – under pressure – Pope Francis was forced to acknowledge.

Finally, on September 21, 2018, Franco, who had stepped down from his post, was arrested.

Several high-ranking clergymen visited him during his 21 days in prison. Franco told me he treated it like a spiritual retreat.

“I read, prayed, interacted with inmates, and told them stories of Jesus,” he said and added, “Only because I would be accused of forceful conversion, I did not baptise anyone. Otherwise, I would have done that too.”

Meanwhile, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) issued a statement expressing “deep pain” over the nun’s accusations and criticised the media for “constant attacks on the Church.”

The message from the Catholic Church was clear: Franco would not be abandoned.

On October 15, when Franco stepped out on bail, grand celebrations took place in both Kerala and Jalandhar, organised by his followers.

He spoke to the media, framing his case as a spiritual crisis endured by the Catholic community. “In this case, only three people know the truth – the complainant, me, and God,” he told the media. “Let the truth prevail.”

Throughout this period, Ruth stayed inside the convent. She only stepped out to give her testimony in court when the trial began in September 2020.

Ruth was cross-examined by Franco’s legal team for more than 10 days. “I cried endlessly and felt stripped of all my dignity.”

It was the only time she had to face Franco.

“They [court] asked me, ‘Is it this man?’ He was standing far from me. I looked at him for a second and turned away,” she said.

Raman Pillai, Franco’s advocate, is known for his shrewd, ruthless, and dramatic ways.

“There were some questions which entirely broke me,” Ruth said, recalling how he would sometimes repeat the same questions until she cried out in distress.

At times, the judge intervened. “He would tell Raman Pillai that there’s a limit to how you can ask.”

Franco had a very different recollection of his 105 days in the accused box.

For him, the trial made him feel similar to Messi and Ronaldo. “They don’t care what the crowd is saying. They only look at where the ball and goalpost are,” Franco said when we met in July. “Either you have to dodge them or hit them [the opposition], or pass the ball and save yourself,” he told me.

He took pride in the fact he was acquitted, even though none of the prosecution witnesses turned hostile. He said he was under pressure to “buy witnesses.” His lawyers, he said, told him the case cannot be won “without manipulation”.

Franco claimed he disagreed. “I said your interest is up to the fees that I pay you. I never bargained. I am paying you what you ask. So enough with that. [sic]”

Meanwhile, life inside the convent had become unbearable, not just for Ruth but for the five nuns who stood by her. The eight others, loyal to Franco, refused to speak to them, stripped them of all duties, and kept them under constant watch, tracking their movements, conversations, and visitors.

Neena recalled how the pro-Franco nuns would lurk and listen. “We’d turn a corner and suddenly they’d be there,” she said. “We started whispering to each other. It was so eerie.”

To break the unity of Ruth and her allies, the Church sent each of them multiple transfer orders. No one complied.

“I really thought I was losing my mind, going mad. We cried a lot,” said Neena. “There was no purpose to life.”

Ruth would sink into depressive episodes and often speak of suicide, Neena added. Despite their own sense of hopelessness, they made sure Ruth was never alone.

“So what did you do?” I asked.

“We got some chickens,” Neena said, bursting out laughing. “We call them ‘case chickens’. There were also ‘case fish’, but many of them died.”

The fish and chickens were gifted to them by well-wishers during the trial. “Just to keep us occupied. Now we’re attached to them,” said Neena.

Some of them crowdsourced a stitching machine for Ruth. “This was to help me spend time, because I never stepped out back then,” said Ruth.

Ruth’s family also stood with her.

Kochurani, a feminist theologian, is one of the founding members of the Sisters in Solidarity (SIS), a collective founded in 2019 by a group of Catholic women to support Ruth and other survivors.

The SIS and SOS groups and the families of the nuns came together to offer financial, emotional, and spiritual support. The nuns began growing their own vegetables. “We tried to engage them in studies. They took a few computer classes and learnt stitching,” said Kochurani.

The SIS also began conducting offline and online therapy. “We did movement therapy and spirituality sessions,” she said.

However, sister Josephine, who had been the closest to Ruth, began to crumble. The isolation got to her. On October 4, 2021, she removed her habit and left the convent for good. She was done.

Josephine spoke to me from Andhra Pradesh, where she now teaches at a school. “Call me Priya,” she said, referring to her birth name.

The intensity of her faith, she claimed, has not changed. But, “I’ve learnt that we need to move from being trapped in mere religiosity towards a more spiritual outlook.”

After 27 years of convent life, she now had to start all over again. “I didn’t even have a basic understanding of how to dress, what colour I like or how to interact with people,” she said. Her family wanted her to get married, but she “doesn’t see a need for it.”

Whenever she travels to Kerala, she still visits Ruth.

Chapter 7: Judgement

On the night of January 13, 2022, the pro-Franco nuns spent hours on their knees, praying loudly and conducting candlelight processions inside the convent.

The verdict was due the next day.

Ruth did not sleep well. The next morning, the nuns crowded into a room to watch the news. They did not talk much.

At exactly 11.02 am, the verdict was announced. “Franco Mulakkal kuttavimukthan aanu,” blasted the news channels.

The nuns were confused. They did not know what the word ‘kuttavimukthan’ meant. It translates to “a man free of fault,“ meaning he was acquitted.

Then came a new wave of confusion. How could this have happened?

Outside the convent, reporters waited for a reaction. But no one moved.

They waited for Father Vattoly to return from court.

Father Augustine Vattoly, a senior priest in Kerala’s Ernakulam diocese, is known for his progressive ways.

He is one of the few clergymen who publicly supported the nuns and is the convener of the SOS group, which co-organised the sit-in protest demanding Franco’s arrest and the legal funds for Ruth.

When the judgement was delivered, he was inside the courtroom. “Dead silence” is how he described the room, the police officers, lawyers, and even the streets outside.

“People were shocked,” he said.

When Vattoly reached the convent, the nuns broke down. “It felt completely hopeless,” he recalled.

The Special Investigation Team (SIT) in the Bishop Franco case led by IPS officer Harishankar S put together an array of witnesses and not one of them backed out in court. Judge Gopakumar G set Franco free and issued a 289-page judgement steeped in outdated and patriarchal reasoning.

While he did acknowledge the complexity of reporting sexual violence within the Church’s power dynamics, paradoxically, he used this very struggle to portray Ruth as an unreliable witness who had exaggerated her account.

Despite her relentless efforts to file a complaint with the Catholic Church, he emphasised what he saw as a central flaw: “The long delay in reporting the matter remains unexplained.”

The judge dismissed all the letters Ruth wrote to the Church in India and the Vatican. He found them unreliable.

He focused on her interactions with Franco after the alleged rapes – like the time she accompanied him for her nephew’s Holy Communion.

The judge also reprimanded the nuns for holding a public protest.

His approach became clear with the way he dealt with Ruth’s cousin Jaya and her spiritual mother, Lissy.

Lissy told the court that after giving her police statement against Franco, the Church had taken her out of Kerala and kept her “under confinement.”

During that time, fearing expulsion from the Church, Lissy wrote to a superior saying the police had coerced her into speaking against Franco.

In court, she said that she had lied in an attempt to protect herself and Ruth. These contradictions made the court question her credibility.

But Jaya’s conflicting testimonies were not only entertained but appeared cherry-picked by the court. She admitted that she had falsely accused Ruth and her husband of an extramarital affair.

However, Judge Gopakumar questioned whether “a lady of Jaya’s stature” would malign her husband without cause and suggested Ruth’s rape allegation was a ploy to “cover up” this affair.

Ruth told me that Jaya attempted to contact her via phone and through other nuns. “Jaya tried her best to inform me that the priests had approached her and were pressuring her to give statements,” she said. “But I did not speak to her because I was angry.”

Since the verdict, the two have not spoken.

I contacted Jaya to seek clarity. “I do not want to speak about this,” she said.

What remains the most glaring aspect is that Ruth was subjected to the banned two-finger test.

Historically, this test – a procedure meant to determine whether a woman had been sexually active based on vaginal laxity or hymenal rupture – was used to find out if the hymen was intact or not.

Recognising its lack of scientific validity, “its cruel, inhuman” and “degrading” process, the Supreme Court of India banned the test in 2013, ruling that it had no place in modern medical or legal practice.

But Judge Gopakumar admitted its findings and used them to shift focus from the allegations of rape to the nun’s moral character.

Franco has a disturbing theory that he calls the finger-position test.

He told me that during the medical examination, “If only one finger enters the vagina, she is a virgin. Two fingers means she’s having a relationship only with one man, her husband. But used by multiple men – that’s the three-finger position.”

What is the scientific validity of this theory? What law legitimises this? He had no explanation.

“I know very well why this case came about. Because in 2016, the nun’s cousin [Jaya] gave a complaint,” Franco added.

The judgement is also a product of the legal blind spot caused by canon law and a country’s law.

The Catholic Church is governed by the Codex Iuris Canonici (CIC) or the Code of Canon Law – a comprehensive system of laws and principles that governs the Church’s spiritual, administrative, and moral conduct.

For the Catholic Church, the canon law holds greater authority than a country’s penal code.

Throughout the trial, not one of the six priests to whom Ruth confessed nor any of the Vatican officials were called to testify.

Anita Cheria, a feminist campaigner, writer, and a close confidant of Ruth, explained that there is little incentive for priests to report such crimes because canon law can punish those who violate the seal of confession. “But it’s not as if people never break it. Priests do – when it suits them.”

Judge Gopakumar pointed to internal conflicts among nuns and priests, claiming how they reflect Ruth’s “desire for power, position and control over the congregation.”

Ultimately, Franco was not acquitted on grounds of innocence.

Instead, the judge stated that “when grain and chaff are inextricably mixed up, the only available course is to discard the evidence in toto.”

Ruth never read the judgement. She does not intend to.

Chapter 8: Blowback

The story did not end with the verdict. It never does.

We accessed 33 letters exchanged between Ruth and various authorities within the Catholic Church between March 2022 and June 2025.

Of this, three letters were addressed to Archbishop Leopoldo Girelli, the new Apostolic Nuncio of India and Nepal. She also wrote five letters to the Vatican.

“We have knocked on every single door we know,” Ruth said.

After the trial, Ruth’s letters pleading against institutional retaliation elicited replies. But each only deepened her distress, as she felt the Church’s sole aim was to “destroy” her and her ally nuns.

It began slowly. The pressure was mounted on them strategically.

The state security granted to the nuns continued after the verdict. The first three months were quiet.

By this time, Sister Josephine, one of Ruth’s closest allies, had already left the convent.

Again, Ruth and her remaining four ally nuns received transfer orders to different parts of the country.

They wrote back explaining their inability to leave the Kuravilangad convent, as they had been granted police protection under the Witness Protection Scheme. The case was also under appeal at the Kerala High Court.

Then a flurry of letters arrived from Jalandhar. The nuns were told that they were “not leading religious lives” and given ultimatums to accept the transfer orders.

“Canonically,” Bishop Agnelo Rufino Gracias of Jalandhar told the nuns the diocese was “in a very difficult position.”

Ruth’s convent was going to be shut down, and if they refused to move, they would cease to be members of the Missionaries of Jesus congregation.

They desperately pleaded with their superiors. “We are also human beings” who have dedicated “our lives to missionary service. We have no independent source of income and have no residence to go to,” wrote Ruth to her superiors.

In May 2023, the pro-Franco nuns packed their bags and left. They told Ruth that the convent will now be considered shut. They also took the gardener and the kitchen helper with them.

“On their way out, they painted over the signboard that said ‘Missionaries of Jesus Congregation’,” Ruth added.

Financial control is central to the Catholic Church’s fiduciary structure.

Unlike some orders that allow personal savings, the Missionaries of Jesus permitted none. In her 26 years as a nun, Ruth never saved a rupee for herself. She handed over everything she earned to the congregation, in keeping with her vow of poverty.

In return, the congregation gave each nun a monthly stipend of Rs 5,000 for food and essentials and covered their medical bills.

Even during the trial, the Church had refused to pay legal or travel expenses.

Advocate John S Ralph, who represented Ruth, worked pro bono. All other legal expenses, including each trip to the courthouse, were supported by SIS and SOS.

In September 2023, Ruth and her allies were given two choices: take a three-year leave of absence or accept exclaustration.

According to canon law, exclaustration is a temporary separation from a religious institute that can be imposed as a disciplinary measure and does not normally extend beyond three years.

“You have to make a choice,” Bishop Angelo wrote to Ruth, warning that if she didn’t comply, the nuns’ financial allowance would be cut off.

Ruth saw it as a calculated effort to break their spirit and force them out. “They don’t want to dismiss us. That would look bad. Instead, they did everything to push us out. But why should we leave? We became nuns by choice. We did nothing wrong.”

By October 2023, their stipends stopped.

Worried, Ruth wrote a letter to Cardinal-Bishop Luis Antonio Gokim Tagle in the Vatican, one of the most senior-ranking cardinals in the global Catholic hierarchy. He was also in the run for pope following the death of Pope Francis.

She detailed her “unbearable” living conditions and sought his urgent intervention. “Should the victims of clergy sexual abuse be victimised further for bringing out these issues instead of covering them up? Shouldn’t a situation like ours, which is exceedingly torturous, demand new ways of resolving it?” she asked him.

He did not respond to Ruth’s letter.

In 2024, she wrote three more emails to the Vatican office. She asked for an explanation: “How would you respond to the plight of a survivor of sexual assault within the Church?”

She did, however, receive one response from Rome in May 2023. This was the only time she received word from Pope Francis.

Roberto Campisi, the deputy chief of staff in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State, wrote back referring to her letter to Pope Francis. “His Holiness, through me, thanks you for the feelings of trust while assuring you of a special remembrance in prayer.”

For Neena, the youngest of them, the pressure and loneliness became unbearable. She lost her father during the trial. “He was so sick, and I was so preoccupied with the case …” she said, breaking into sobs. “Everything had got so messed up…”

After the verdict, “I took my rosary and put it in Ruth’s hand. We hugged and cried,” she said.

But after leaving the convent at the age of 34, returning to her family wasn’t easy. “It was humiliating. Suddenly everyone wanted me to get married,” Neena said. Soon, she moved into a hostel and began working for an NGO.

She now goes by her birth name. She questions everything about her relationship with the Church. And with God. “I don’t like the identity of being a nun anymore. After going through all this, I kept asking myself, ‘Where is God? Is He not seeing all this?’”

Chapter 9: Frankly Franco

When the case was filed against him, Franco said his loudest defenders were the women whose causes he worked for in Punjab.

“They even went on TV and said, ‘Now let us take for granted that our bishop has such [sexual] needs. For that, he doesn’t need to go to Kerala. We are here,’” he said, doubling over with laughter.

We were sitting at the retreat centre in Kerala’s Kottayam district where he now lives. The place is bare and only visited by locals. It’s a world apart from the power, position, and prestige he once commanded as Bishop of Jalandhar.

Franco won’t admit it, but he is fuming – mostly against women. “Should women be allowed to even exist? Tell me, should they?” he asked, leaning forward in his seat.

“What do you think? Should they exist?” I asked him.

His reply was swift. “Well, if AI (artificial intelligence) is developing, and plastic dolls can produce children, then why do we need women? If women are only for sex, you don’t need them.”

He took a moment and quickly added, “But they’re not only for sex, no? There’s also companionship.”

Franco believes that there is no rape in India. “Rape cannot be reported,” he said. I was confused.

He used the term “righteous rapist” to explain that a man who rapes will always “kill” his victim. Because, as per law, a woman’s testimony is paramount. If she lives to tell her story, the man “cannot defend himself.”

Hence, he said, all the rapes reported by women who are alive are “false.”

He believes that his case stemmed from the collective jealousy of other clergymen who used Ruth “as a pawn” to disrupt his rapid rise to power. “They made her accuse me of rape, giving her full guarantee that she will win the case. Rape is the best,” said Franco. His removal gave the other men a shot at the seat in Jalandhar.

In the four hours that we spoke, he oscillated between being the accused, victim, lawyer, journalist, judge, and martyr. He often placed himself next to Christ.

A few days before the trial began, Franco lamented to Jesus, “You raised me up, but I’m on the cross,” he said, framing his trial as his crucifixion.

Jesus apparently told him, “I am on the cross next to you. You are not alone.”

Franco said he was relieved. “It’s a privilege, no? To be on the cross alongside Christ.“

In the Bible, two criminals were crucified next to Christ. The Gospel of St Luke records their conversation. One mocks Christ, asking why, as the Messiah, He cannot save all three of them.

The other criminal stops him and says that, unlike the both of them, Christ is not a criminal. “We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve, but this man has done nothing wrong.” He then asks that Christ “remember” him in Heaven.

For this act of repentance, Christ promises the second criminal, “tonight, you will be with me in Paradise.”

Franco referred to Ruth as the most “powerful lady” that he has seen. “She will not care even for bishops,” he said.

When asked about the fiduciary relationship between the nuns and clergy, he pointed out how sainthood, the highest position in the Church, is occupied by more women than men.

In the Catholic faith, to be bestowed with sainthood, the deserving individual has to die first.

“So you tell me, who is more powerful? More influential?”

What did he make of the 2002 Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigation that exposed decades of sexual abuse by hundreds of Catholic priests and its cover-up?

“All fake, all fake,” he said and referred to the accused priests as “poor and defenceless.”

Even as he brushed off the idea of the clergy’s power, Franco came alive while speaking of the authority he wielded as a bishop.

He spent nearly an hour explaining his political connections, the work he had done, and the way people and politicians flocked around him. One time, he sat up straight and said, “You know, people called me ‘Jalandhar ka Raja’ (King of Jalandhar).”

Franco now holds the title of Bishop Emeritus of Jalandhar, an honorary distinction given to retired bishops who are recognised for their past services.

Months before his resignation, he met Pope Francis. “I told him, ‘I am Bishop Franco, the rape accused but acquitted.’”

Pope Francis, he said, was shocked.

“I suffered a lot, but I offered all my suffering for the purification of the Church and for my own sanctification,” Franco said he told the Pope.

Apparently, Pope Francis then took Franco’s hands in his and said, “Please pray for me too.”

Franco was never reinstated to his position – not when he got bail, nor when he was acquitted.

“The law of the country has stood by me. It has stood for the truth,” he said, adding, “Did the Church respect the law of the country? What a big wrong signal is the Church giving?”

The Church as an organisation, he said, has become a “liability, but as the body of Christ, it is thriving.”

Towards the end of our four-hour conversation, Franco said that he often felt like Job from the Old Testament – a righteous man whose faith was tested by undeserved suffering.

He said he often asked Jesus why he was being tested. “Then in a clear voice, I heard Him say, ‘Franco, I know. I have raised you up as an example of how to accept a cross with both hands happily.’”

In response, Franco told Jesus, “Lord, I shall do it in your honour.”

Franco repeatedly insisted to me: “I am not defeated.”

Ruth may have lost her case, but it remains an undeniable fact that the size of Franco’s life has considerably shrunk.

Chapter 10: The highest bench

If Ruth has put her entire life at stake for this case, the other nuns also put their entire lives at stake for her case.

On many occasions, Ruth insisted that I visit Lissy.

“You must go see what they did to her, the way she’s living now,” she said.

At 63, Lissy lives in the Jyothi Bhavan convent, 33 kilometres from Ruth. Or rather, in a small room on the convent grounds, with a separate entrance. It is filled with religious paraphernalia, her bed, a small kettle, some tea bags, and a plastic box full of snacks.

“I want to be able to offer something in case I have a visitor,” she said, handing me a biscuit.

Five other nuns live in the convent, which is part of the Franciscan Clarist Congregation (FCC). They don’t speak to Lissy, they don’t look up when she passes by, they don’t eat with her, and they don’t do their laundry with her.

Her food is set aside separately, and she is not spared a single extra morsel.

Two policewomen lounge on a bed right outside her room. Lissy knows all about their children, family problems, and health issues. They’re her only company.

“All of this is because of one thing. I stood by Ruth and testified against a bishop,” she said. “I am confined to this life now.”

Lissy has traversed across India. She loves meeting new people and singing. But for the past seven years, she has lived, eaten, prayed, and sung in this small room. She steps out hardly four times a year, almost always to visit Ruth.

After the verdict, the Church had made an offer to Lissy. She could move to a convent in Andhra Pradesh. She declined.

“Until Ruth dies and goes to heaven, I will not be free of my duty to her as a spiritual mother. This is a journey I have embarked on.”

What must it take to live a life entirely shaped by someone else’s reality, hinged on someone else’s release?

Father Vattoly also faced the Church’s wrath. He was served multiple show cause notices, accused of having Maoist connections and disobeying the hierarchy, and was ordered not to participate in the protest against Franco. But he too remained steadfast.

But in April 2025, Sister Anupama, the public face of Ruth’s protest, also exited the convent. This left only Alphy and Ancitta by Ruth’s side.

It is a well-known fact that for decades, the Catholic Church across the world has housed sexual abusers and actively concealed their crimes.

“The Church knows what is happening. They know what Ruth is saying is true,” Vattoly said.

Even for Ruth, it was not simple.

Vattoly and her family accompanied her to every court date where she had to graphically detail the alleged rapes. One particularly tough day, Ruth stepped out of the courtroom, exhausted and unusually quiet.

Vattoly took her aside. “I feel guilty,” she said.

“Why, what guilt?” Vattoly asked.

“I feel like I am maligning the Church,” she told him.

“You see the depth of the indoctrination?” Vattoly recalled. “Her pain was so deep, not just because of Franco but the court, the trial, the media, the police, and the Church’s onslaught she faced was unimaginable.”

Feminist campaigner Anita Cheria also reiterated this. “A written complaint is so rare. Responding to abuse does not come naturally to religious groups. Just like it doesn’t come naturally to many adults in the family.”

Ruth may have legally lost her case, but her story will be etched in time for achieving multiple breakthroughs.

Usually, when the Church gets even a whiff of clergy sexual abuse, Vattoly explained, the pattern is predictable – the nun is ousted, and the accused priest or bishop is promoted or quietly transferred. But in this case, even after his acquittal, Franco was not reinstated. Instead, he was asked to resign.

”That never happens,” Vattoly said.

Kochurani explained that this is the first time, “even globally,” that a religious woman has remained within the establishment and challenged her patron against abuse. “It has really frightened the Church and shown that women are not going to keep quiet anymore. The victory is in this very fight,” she said.

This is why Ruth’s very act of filing a case against a bishop rattled many within the Church. “Now their struggle [Catholic Church] is that after one nun came out, another should never,” said Vattoly.

The post-verdict response of the Church also raises a deeper question.

Not defrocking, reinstating, or transferring Franco says a lot about the case and the Church, pointed out Kochurani.

“The explanation offered was that the Jalandhar diocese was divided on Franco. The Church is quietly trying to pretend that they’ve offered some justice to Ruth as well,” she said.

What remains most striking is that at no point did the Catholic Church conduct an independent inquiry into the case.

“If the Church was really determined to know the truth, they could have constituted a fact-finding team. Ruth asked for it after the verdict as well. But the very fact that they refuse to do it stands as a big question mark,” said Kochurani.

It has been two years since Ruth appealed her verdict at the High Court. No date for a hearing has been set. It doesn’t faze her.

“What is the hurry? I am anyway not going anywhere,” Ruth said. It’s not patience, but a lack of hope from the court or the Church. “Now, my wish is to live peacefully and do some stitching.”

In this entire process, the exit of her three ally nuns has been painful. She breaks down at every mention of her only companions, her human shields, her strength.

But Ruth is not upset with them.

“They stood with me during the toughest days. Now, the time has come for me to stop depending and stand on my own,” she said. In fact, she told Alphy and Ancitta – the two remaining nuns – that they too must leave if they feel like it.

My last conversation with Ruth was painful. She cried a lot. A burden of silence has accumulated within her. “I will die in this place now,” she said.

Ruth does not believe in closure. It’s too simple a concept to apply to a case so layered.

“I would have preferred it if the Church had sorted this out quietly,” she said.

But in the last two years, as the Catholic Church came down on her, Ruth’s resolve has hardened.

“I’ve been pushed to a corner. I have nothing left to lose now. I don’t intend to back down one inch,” she said. “At least now, the fear has entered the Church.”

Ruth said she often wondered about what meaning to extract from a life lived like hers. But with time, looking into the eyes of her allies – in their conviction – she has slowly come to realise the archival value of her fight.

Witnessing history being written in real time is stunning, but watching it unfold is actually quite baffling.

For everyone involved in this religious tragedy, their competing ideas of heaven and hell and their sense of sin, guilt, shame, and even justice stem from Christ.

Franco frequently pulls Christ into the conversation, using Him to locate, absolve, and justify his life.

But for Ruth, though her entire existence is shaped by her marriage to Christ, her relationship with Him is now a private affair. “I have faith. It’s all I have, actually. It’s tough to explain,” she said.

To her, it no longer matters whether the building is considered a convent or whether she is recognised as a member of her congregation, whether she is written about or not. She continues to live guided by her belief, devoting herself to her duties. Every single day she wakes up, dons her habit, her veil, her rosary – and bears her cross.

“I came here to be a nun. I will continue to live as one,” she said. “I won’t let Him down.”

It is ultimately a story tethered to one entity – Christ. And one question: What would He think?

*Name changed

Ahana Bhalchandra Walanju, Karthika S, Gokul S Vijay, and Neelima Indraganti contributed towards the research for this article.

TNM had sought a meeting with Leopoldo Girelli, the Apostolic Nuncio of India. His office said, “This Office would like to inform you that His Excellency normally does not give interviews.”

TNM sent detailed questionnaires to the following people:

➨ Two emails were emailed to Bishop Agnelo Gracias of Jalandhar. He stated he was out of town and would require time. This story will be updated if and when he responds.

➨ Two emails were sent to the Apostolic Nunciature of India and Nepal. We received no response.

➨ Cardinal-Bishop Luis A Tagle. We received no response.

➨ The Apostolic Nunciature of Brazil. We received no response.

➨ Archbishop Giambattista Diquattro, the former Nuncio to India whom Ruth initially wrote to. We received no response.

➨ To Cardinal Artime, Pro-Prefect of the Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life in the Vatican. We received no response.

➨ To Sister Simona Brambilla, Prefect of the Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life in the Vatican. We received no response.

➨ To the Dicastery for Communication (DPC), the Vatican’s central communications office. We received no response.

Our latest Sena project tracks how elites take over public spaces in urban India, and the price that’s paid by you. Click here to contribute.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.