They sat alone in the small locker room, alternately trying to ignore each other and making awkward, nerves-concealing small talk. Even underground at Roland Garros—and then on the red clay tennis court above—there were contrasts that could not have been more obvious.

One was a lithe Floridian, then 20, a righty whose personality expressed itself in her precise tennis, predicated less on power than composure and calm. The other was 18, about to defect from what was then Communist Czechoslovakia. She was an athletic lefty, who, even as a teenager, had a hell of a risk threshold, charging forward on the court—and speaking her mind off of it—come of it what may.

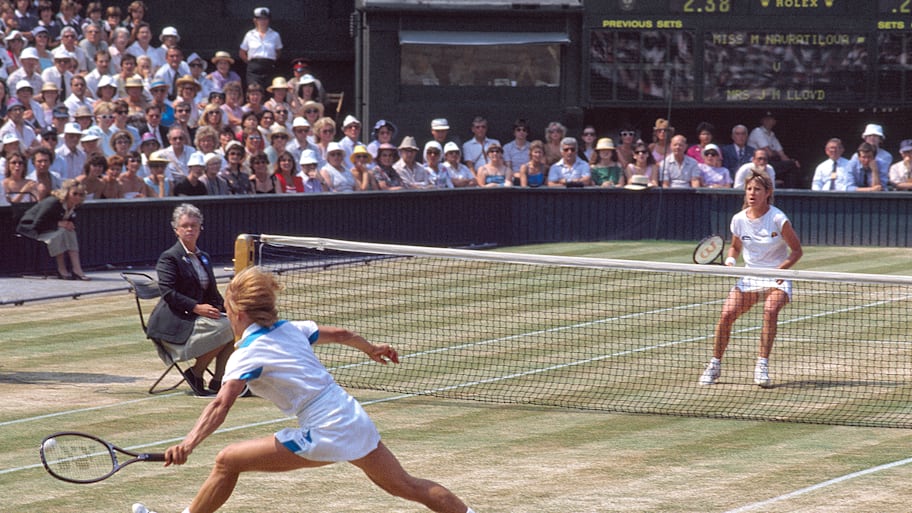

It was 50 years ago this month that Chris Evert (seeded first) and Martina Navratilova (seeded second) met for the first time at a tennis major. That warm Parisian Saturday, in the finals of the 1975 French Open, Evert’s ice would get the better of Navratilova’s fire.

After losing the first set in less than an hour, Evert reset. “I got my—I need to watch my language here—got my act together,” she recently recalled. Evert prevailed 2–6, 6–2, 6–1, marking the second of what would be a women’s record seven French Open singles titles that she would win.

No one knew it at the time, of course, but with this high stakes match, one of the towering, textured rivalries in sports history was officially underway. After that first encounter, Evert and Navratilova would carve their ways through draws and meet in 21 more majors—mostly in the finals, with the trophy on the line. They would play each other on all surfaces, all over the world, at all different phases of their lives. “With all different hairstyles,” Navratilova is quick to add.

Sometimes they would share food in the locker room before their showdowns; other times they would avoid eye contact. Always, they entered events prepared to meet the other.

Early on, both Evert and Navratilova (Chrissie-n-Martina as they inevitably would be known, as their pairing became so numbingly familiar) had the good sense to recognize the power of rivalry. If competition elevates performance, rivalry is competition with an affixed turbo motor.

All sorts of social science confirms this. Studies show that when recreational joggers can pinpoint a rival in their running club, their times improve more dramatically. In business, companies with a clear-cut rival—Coke versus Pepsi, Chevy versus Ford—innovate and drive revenue more than companies without an obvious marketplace competitor. (Steve Jobs would openly credit Microsoft and then Google for their roles in helping propel Apple to new heights.)

Same with sports. Rivals may take the equivalent of market share from each other. But, ultimately, they elevate the output. “Would I have won more if Chris hadn’t been in the way? Probably,” says Navratilova. “But even at the time I knew I was better for having her around. We made each other better. We made each other get better.”

In all, they would play each other 80 times from 1973 to ’88, with 61 of their meetings occurring in tournament finals. Their head-to-head record ended up 43–37, advantage Navratilova. (During that time, one or the other would hold the top ranking for a combined 592 weeks, more than 11 years.) In the end, they would each win 18 major singles titles, bracketing them in tennis’s record books for posterity.

More remarkable still: their relationship post-tennis. Evert hung up her racquet in 1989; Navratilova retired from singles in 1994, and from doubles, improbably, in 2006, just shy of turning 50. Even before then, both realized they would be better off leaning into their dynamic.

If the dynamic of an active rivalry put social boundaries between them, post-competition they became legitimate friends. For a time they both lived in Aspen, where Navratilova helped introduce Evert to skier Andy Mill, to whom she would be married from 1988 until 2006. When both women started working as commentators at various tennis events, it was only natural they would dine or get drinks together after work.

When both were in their 60s, they experienced an unhappy symmetry. At this point, both were living in south Florida, each an easy drive from the other. In 2020, Evert lost her sister Jeanne to ovarian cancer. Navratilova not only attended the funeral, but also stayed with Evert and her family until late that night. In late 2021, Evert—inspired by Jeanne—underwent genetic testing and learned she was positive for the same mutation. Shortly thereafter she found that she had ovarian cancer.

In a beautiful Washington Post profile by Sally Jenkins (full disclosure: the story is the basis for a documentary I am helping produce) Navratilova said she wore a Cartier charm necklace for good luck when Evert went through six cycles of chemotherapy.

Evert was still fighting her battle in late 2022, when Navratilova received her own unfortunate news. She, too, was diagnosed with early-stage cancer in her throat and breast.

Rivalry had, if you’ll forgive the word choice, metastasized into something much deeper. When Navratilova was in the cancer depths, Evert would help pull her out. When Evert was returning from chemo and without an appetite, Navratilova would deliver food and make her eat. When both anxiously await scan results, each is there for the other.

They convalesce together. They text. They drink wine together. (While Chris and Martina share a couch and a bottle of chardonnay, note that their contemporary male rivals, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors, still can barely be in the same room together.)

Evert, now 70, is the mother of three boys, a recent grandmother, and a positive force on social media. Navratilova, 68, has been married to Julia Lemigova (of Real Housewives of Miami fame) since 2014, and is both a stepmother to Lemigova’s two daughters and mother of two boys the couple adopted last year.

Chris and Martina continue to marvel at how impossibly far removed they are from 1975. “What do they say? Life is what happens when you’re making other plans,” says Navratilova. “When we were sitting there in 1975—we were so young!—did we think this would be us in 50 years? We did not.”

And yet, as their rivalry has come to veer toward sisterhood, they both express surprise that more rivals don’t grow similarly close. As Evert once explained to me, in their competitive primes, she and Navratilova often thought about each other. Their experiences mirrored each other’s. Of all the people on the planet, Navratilova came closest to knowing what Evert was going through. And vice versa. “It’s almost like, how could we not be close?” says Evert.

A half century after their maiden major final—owing to a combination of broadcasting work and sponsor duties—Chris and Martina will both be back in Paris this month for the 2025 French Open. They have already made dinner plans.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as After 50 Years, Navratilova and Evert’s Rivalry Has Morphed into a Lifelong Friendship.