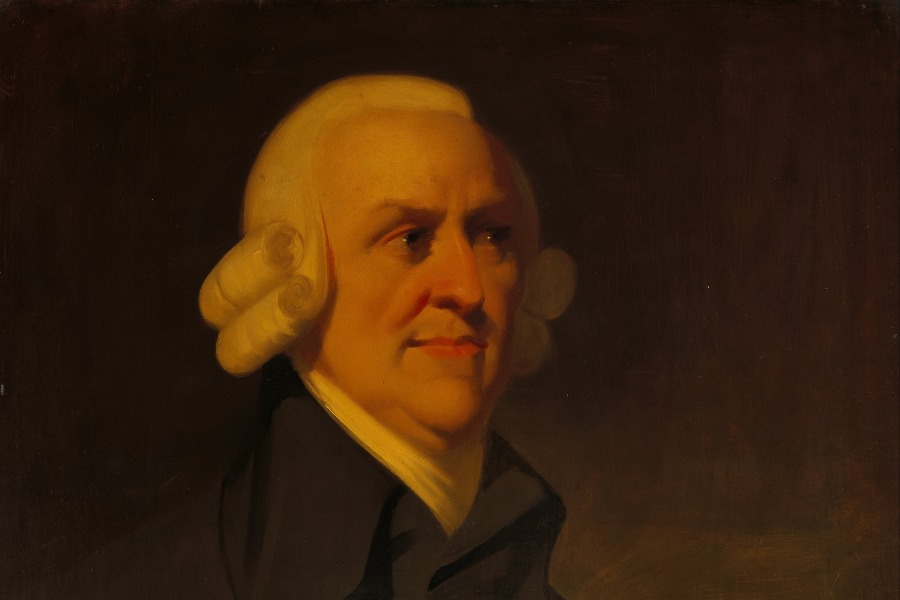

AS a toddler, Adam Smith, was apparently kidnapped by gypsies and needed a horseback rescue from Fife’s deep woods by his uncle with a posse of friends and neighbours.

Nobody can be sure of the truth of this story about the four-year-old who grew up to earn from the world the informal title of Father of Economics.

But it is the sole information we have about anything in his childhood, otherwise spent living quietly with his widowed mother on a stair in Kirkcaldy High Street. She was devoted to him, and even in adulthood made sure he always had a safe and cosy place under her roof to work at his great ideas.

During her lifetime the family had come down a bit. The elder Adam, the economist’s father, studied law and started a promising career as private secretary to one of the last secretaries of state in independent Scotland, the 3rd Earl of Loudoun.

But in 1707 he lost this job and nothing as good could be found to replace it – a common fate for public servants at the time of the Union. Fobbed off with a minor post in charge of the customs at Kirkcaldy, he never ceased to complain. He was still doing so at the time of his premature death early in 1723.

That left everything in the hands of Mrs Adam Smith, Margaret Douglas, daughter of Robert Douglas of Strathenry, of a prominent farming family in Fife that had also supplied members to the Parliament in Edinburgh.

These were not beneficiaries of the Union, but they never complained. She got help from relatives and friends who had been made guardians of the younger Adam in his father’s will – James Oswald of Dunnikier, a wealthy merchant in Kirkcaldy, and Smith’s cousin, William Smith, the 2nd Duke of Argyll’s steward. But there was something prophetic in the story of the gypsies.

Today scholars and pundits can again kidnap Smith to explain that he never meant what he wrote in two of the most influential books in western intellectual history, The Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations. Instead, supposedly, he was struggling to agree with them.

Even UK prime minister Gordon Brown, who was himself a pupil at Kirkcaldy High School, had a contribution to make to this folklore. There are people who regard themselves, like Brown, as socialists and define Smith as a proto-socialist, or even as a precursor of Karl Marx. To be fair, Marx did adopt one of the few ideas Smith was wrong about, for example that the value of anything is determined by the labour that goes into it.

It is easier to get things wrong if you need to think them all out from the start for yourself. The wonder is rather that Adam Smith so seldom went astray. His education followed the normal curriculum in the two rooms of the school Kirkcaldy had in those days, learning Latin and a little Greek, Roman history, rhetoric and grammar, and arithmetic. Later he commended the system, while hinting he would have liked more “geometry and mechanics”.

Clever Scots lads started higher studies at the age of 14, and Smith did so at Glasgow University in 1737. By European standards it might have looked remote, but it was well up in science and philosophy. The teacher Smith liked best was Francis Hutcheson, professor of moral philosophy, one of the first to lecture in English rather than Latin, and to abandon rigid Calvinism as the intellectual structure of his teaching.

Glasgow could also offer its students a long step into the wider world with the Snell scholarships. They were awarded to its best students for at least three years of study at Balliol College, Oxford.

England gave Smith not just challenging views but also novel experience. After he rode away from Kirkcaldy, he entered a different world at the Border. He wrote to his mother about the grand buildings he saw and the fat cattle compared to the skinny beasts at home.

Most important was that Balliol had one of the best libraries in Europe. Smith found the chance during his years there to master ancient philosophy and get to grips with modern English, French, and Italian literature. They taught him lessons he repeated in his own books.

Yet it would be wrong to suppose Adam Smith just followed other Scots’ example and felt overawed by an institution like Oxford University. He would not admit it had any universal superiority. A small problem he soon identified was that the teachers got paid directly from the endowments of the colleges, and not from students’ fees, as they were in Glasgow.

“In the University of Oxford,” wrote Smith, “the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” Instead, the colleges were organised “for the interest, or more properly speaking, for the ease of the masters.” There were disciplines imposed on the students but none at all on the teachers.

So far from being bowled over by the academic standards, Smith pointed out a lesson from Glasgow to Oxford. The lesson was not just of academic interest, but showed the power of perverse incentives that put people off doing what they should be doing in real life. This was commonplace in the outside world, and the source of many problems there. It is the same today, except the problems have (sometimes) changed.

Far from assuming that an “invisible hand” will direct selfishness to achieve social goals, Smith only used the phrase twice, in discussion of income distribution and production. Yet he had a clear view of “the uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition” and this was why he pointed to the importance of incentives.

Smith became not just an economist but a social psychologist. This was how he continued to extend the scope of his thinking, from Scotland to England, from countries to empires, in the end to all levels of society, on the basis that people are better off making their own economic decisions than having them imposed: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest.”

In 1746 Smith returned to Kirkcaldy, since the terms of the Snell award required him to use his talents in Scotland. His rising scholarly reputation went before him and he soon got an invitation from a learned judge, Henry Home, Lord Kames, to give a course of public lectures in Edinburgh on rhetoric.

Such was their success that between 1748-51 Smith expanded them to include the history of philosophy and jurisprudence. He was appointed professor of rhetoric at Glasgow at the age of 28, and a new chapter of his life began.

In this column I will from time to time continue to follow the progress of Smith’s career, because it seems to me of direct relevance to the economic world we are living in.

Classical economics, which grew out of The Wealth of Nations, had by the end of the 20th century got lost in mathematical abstraction. It is one of the reasons why in the 21st century the system has collapsed, and must now be built anew.