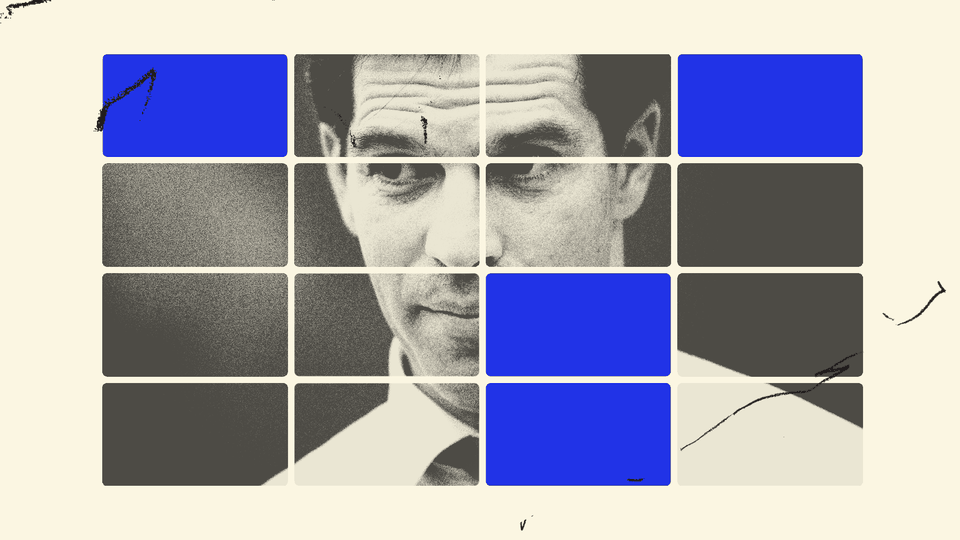

George Santos is, at the moment, still a sitting member of Congress. He somehow manages this despite having been caught fabricating parts of his résumé; despite telling weird, at times disturbing lies (such as 9/11 having “claimed [his] mothers life”); despite having been accused of running multiple dog-related scams; despite calls for him to step down; despite a federal investigation into his finances; and despite a scolding from Mitt Romney at the State of the Union. According to one poll late last month, 78 percent of Santos’s constituents believe he should resign. And yet, Santos insists that he will not (though he has owned up in part to “embellishing” his résumé).

How does a politician decide whether to cling to office or let go? To get an insider’s understanding of the process, I called up Jeff Smith, a former Democratic Missouri state senator who resigned his post in 2009 upon pleading guilty to obstructing justice. Smith admitted to lying to investigators in a campaign-finance-related inquiry, and spent a year in prison for it.

Nowadays, Smith told me he regularly fields calls from panicked politicians hoping for advice on navigating scandal. His playbook tends to lean toward the practical—staying out of jail, fixing one’s marriage—and the occasional reminder that perhaps there is more to life than holding public office.

We chatted by phone last Monday afternoon, discussing the Santos case specifically and whether the resignation calculus for any given politician has changed at all since the election of Donald Trump.

Our conversations have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Caroline Mimbs Nyce: Do you think resignation is a decision, or is it forced upon you?

Jeff Smith: Well, in my case, it wasn’t a decision. I resigned because I had pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice. And once I made that decision, there was no decision about resigning, because, legally, I wouldn’t be allowed to serve. I definitely hear from a lot of elected officials who are going through challenges not unlike the one that I went through.

Nyce: Do you? Do you run a “should you resign?” consulting business on the side?

Smith: [Laughs] I wish I got paid for it. I would probably be retired by now if I charged by the hour, because I hear from a lot of political figures around the country who are experiencing stuff like this.

Nyce: What do you say? What’s in your playbook?

Smith: The No. 1 thing I say is that if what they’re alleging is true, how you go down determines whether or not you can get back up. If you go down saying, “The Feds framed me; my political opponents framed me; everybody was out to get me,” then, in most cases, it’s going to be very difficult for you to come back from that, because you went down lashing out at everybody else instead of taking responsibility for your mistakes. If you drag all the people who backed you into a fight and then information emerges that portrays you in a negative light, then you’ve used up that reservoir of goodwill.

Nyce: When you advise people, what are the factors you look at? Public-opinion polls, viability for the next election?

Smith: What’s the evidence against you? What’s going to come out? What are they going to find when they dig deeper? A lot of people who reach out are at the very front end of this. They’ve gotten a call from the FBI, they’ve gotten a call from a reporter, and they’re freaking out.

Nyce: Do you calm them down? Or do you say, “Yeah, you should be freaking out”?

Smith: It depends. Everyone’s got a different situation. I’ve definitely had some where I’m like, “Look, man, you’re going to be fine.”

Nyce: If Santos came to you today, what would you advise him?

Smith: I would say, “As a human being, I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt and say that you decided to get into this to help people and make a difference and stand up for the things you believe in. But if you’re honest with yourself, you know that you’re not effective in doing that right now. And I don’t envision that changing.”

Nyce: How do you think about the duty to constituents in these situations?

Smith: No one’s going to take you seriously when you go into their office and say, “I’ve got a bill to help the survivors of 9/11. And I’m wondering if you’ll co-sponsor it.” No, they’re not going to co-sponsor your bill right now, because you’re a national embarrassment.

That’s what the legislative process is. It’s going around and saying, “Mr. Speaker, can you refer my bill to a committee? Mr. Chairman, can you give my bill a hearing?” All you’re doing is asking all these people for these things, and you can’t do it with any effectiveness if you’re a laughingstock.

Santos can’t represent his constituents in the way they deserve to be represented. But I understand from a legal perspective why someone would be loath to resign at this juncture. It’s very simple: If you decide to negotiate a plea deal, that’s something you can give them—the resignation of your office. And so a lot of people will cling to the office. There’s an element of selfishness to it, but it’s probably a wise legal strategy—to hold on to that office so you have something to bargain with.

Nyce: What’s something about resignations that most people from the outside don’t realize? What’s it like to be in the inner circle? Or be the person resigning?

Smith: Well, if you’re the principal, you’ve definitely got a lot of people who refuse to believe that you did anything wrong—who are telling you to fight it. Especially in my circumstance. I lied about a campaign postcard—about whether I was aware that one of my aides gave information about my opponent’s attendance record to a third party who put out a campaign postcard. When I was in the very final days, I couldn’t really talk about it with people. But with the very few people that I did discuss it with, it was like, “Why would you resign over that? Compared to what other people get away with?”

Most people who are your closest intimates will believe that you can do no wrong, and those are not the best people to be receiving advice from, because you have to be coldly rational in those moments. It’s very easy and very tempting psychologically, because you are facing this terrible crisis and you’re beaten down, and then you’ve got these people who are your closest allies. And they sometimes are telling you, “No way. We worked so hard for this. We can’t just give it all up.” They’re not necessarily the best people to be taking counsel from. That’s why you should hire a good attorney, because in most cases, you’re in legal jeopardy.

I definitely had some people suggesting, “Oh, you can beat these charges. It’s a fucking postcard.” It’s very tempting to take that advice. But it would’ve cost me millions of dollars to defend myself in court, and there was a good chance I would have lost. And if I’d lost, I’d have gone away for, like, five years instead of, like, a year. You’ve got to put out a matrix and do the math and look at the probabilities and take the emotion out of your decision. That’s my advice.

Nyce: Do you think the resignation calculus has changed in the Trump era?

Smith: Sure. You see a guy that does a dozen things that would have been career-ending for any politician in modern American political history. And he is just like Houdini. Trump changed the rules, and people continue to try to test the boundaries to see if the new boundaries apply to them too. Some people have survived things that nobody thought survivable before Trump. But I’m not persuaded that we’ve seen a permanent change.

I agree with what Mitt Romney said about Santos. What he’s done has shown him to be totally beneath the standards of being in Congress. But what do those standards even mean? Like, Marjorie Taylor Greene is in Congress. What standards do we have? Every standard of qualifications and decorum and civility has been thrown out the window.

Nyce: I’m not a psychologist by any means, but, just reading Santos’s tweets, he doesn’t necessarily seem to be behaving like a politician under siege. What do you make of his cavalier attitude?

Smith: His attitude is nothing like what I encounter. Most people who reach out to me are distraught. They’re like, “How did I make this mistake, and how can I put the pieces back together? And can I save my career? Can I save my marriage? Can I save my freedom?” I try to help people see that there’s a lot more to life, and that there’s not necessarily redemption—it depends on your case—but there’s satisfaction and happiness on the other side, even though it’s hard to see that in the moment.

Nyce: Do you have any sympathy or empathy for Santos?

Smith: Not much. Because there’s no discernible evidence of a core belief in anything other than his own destiny to be famous. When I hear folks tell me their story, it’s like, “Okay, well, you got into this because you cared so much about X, Y, Z, and then you went astray.” When I see Santos, all I see is a lust for stardom and prominence.