Betty Reid Soskin was 92 when she first went viral and became, in effect, a rock star of the National Park Service. She was the oldest full-time national park ranger in the US – this was back in 2013; she’d become a ranger at 85 – but she had been furloughed along with 800,000 other federal employees during the government shutdown. News channels flocked to interview her. She was aggrieved not to be working, she told them; she had a job to do.

“In a funny way, I suppose that started lots of things,” Soskin says. Her memoir, Sign My Name to Freedom, was published in 2018, and a documentary about her work, No Time to Waste, was released in 2020. Another film is in the works. Barack Obama called her “profoundly inspiring”. Annie Leibovitz photographed her. Glamour magazine named her woman of the year. Now, Reid Soskin is 104, and “all of whatever I was supposed to do, I’ve done”, she says.

She retired as a ranger at 100, having helped to establish the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front national park in Richmond, California, where she shared, day after day, the wartime experiences of people of colour, because “what gets remembered is determined by who’s in the room doing the remembering”. At the time, she joked that her job was almost “like I’m running a federally funded revolution ... I was very aware that I was in my 90s and I really didn’t have time to waste,” she says.

Understandably, Soskin’s sense of time has evolved since entering her second century, softening into something more amorphous. “Now that I’ve held on a few more years, I really do feel old,” she says. “Memories are getting dimmer and dimmer, and events feel as if they happened yesterday … and simultaneously many years ago. Time has collapsed in on itself.”

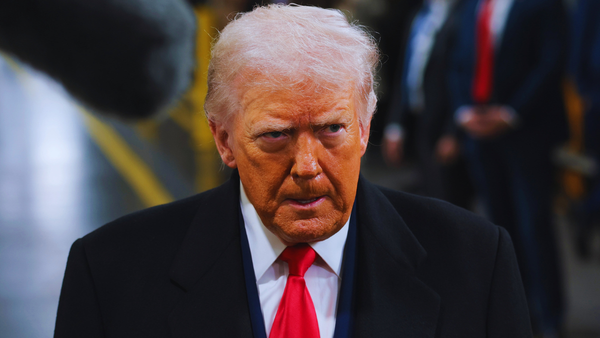

Political events, too – she mentions Donald Trump’s deployment of the national guard to US cities – are collapsing “in on themselves. And I feel as though it’s all of a piece.”

Soskin is still not sitting back. “I follow politics very closely,” she says on a video call from her home in Richmond, where she lives with her daughter, Di’ara. “Even going through the 50s and the 60s with civil rights, that was all [progress],” she says. “I don’t feel as if that’s so now ... It’s seemed to me that [Trump] has no idea what he’s doing. I think we’ve lost our sense of direction. And that’s terrifying to me, because I’m going to leave the world in such a shape.

“I find myself wondering what [the world] is going to look like and I don’t have any idea. This is a time of chaos … We grow through life always thinking there’s something better ahead. And for the first time in my life, I’m not sure there is.”

* * *

Soskin was born Betty Charbonnet, and grew up initially in New Orleans; the family moved to Oakland, California, after the floods of 1927. Her father came from a Creole background, her mother a Cajun background, and her great-grandmother, who lived to 102, had been born into slavery in 1846. But after she came to public attention, new episodes of Soskin’s long and varied life kept coming to the fore. There are many different Bettys – she refers to herself as Betty, as a way to uncouple herself from the men in her life – and for a long time, she says, she didn’t know “who Betty was”.

There was the Betty who had opened Reid’s Records in 1945, one of the first black record shops in California, with her then husband, Mel Reid. There was Betty the singer of protest songs, who surfaced on social media a few years ago in a set of reel-to-reel tapes recorded in her 30s. There was Betty the civil rights and community activist who raised funds for the Black Panthers and later helped to tackle the drug trade in the area around Reid’s Records. There was Betty who worked in local government as a legislative aide. All this before she became famous as the National Park Service’s oldest, and possibly most outspoken, ranger.

It was when “the three men” in her life died – Reid; her second husband, the psychologist William Soskin; and her father – in a three-month period in the late 1980s, that Reid Soskin’s life was transformed. “It’s like I stepped out of one life and went into another,” she says.

“That was actually when my life started. Because I didn’t really know who I was until then. Then I became Betty. Oh, that was wonderful. I really began to see myself as being a part of the world. I began to be in my own shoes. I had things to do – and that lasted until I was 100. I went on doing things. I was no longer becoming, I was simply being.”

In 2015, she was asked to introduce Obama at the national Christmas tree-lighting ceremony in Washington DC. (She had previously declined an invitation to the White House from George W Bush.)

“I remember being led to where [the Obamas] were standing between two flags. And rather than look at the president, I was looking at her [Michelle] and saying out loud, ‘You are so beautiful.’” Soskin had in her pocket that day a photograph of her great-grandmother, Leontine Breaux Allen, whom Betty knew well into her own 20s. I stood there like a page of history,” she says. “I was standing beside the president of the United States. I was standing within the shadow of the White House. And it was built by slaves.”

She holds a commemorative coin up to her camera: Obama slipped one just like it into her hand when he shook it. The original was stolen in a house burglary, so this one is a replacement. “I don’t think there’s ever anything that matches the lived moment,” she says. Mementoes are “like ashes. They’re simply symbols of what was.”

Soskin says she no longer thinks of herself as a feminist or an activist, just “as a person. I never did like labels.” She doesn’t even regard herself as “a singer”; simply as “a Betty who sang”. She started composing songs on a guitar, a Christmas gift from Reid, when their marriage was disintegrating. “I was in the middle of a breakdown, and I thought I was remembering things,” she says, realising only much later that she was actually creating them – “and seemed to have captured all the things that were important”.

She could have been a successful singer. She once performed with Pete Seeger, and after the film-maker Henry Hampton heard her at a Unitarian convention, she says, “he convinced me that I could sing, and he had me come to Connecticut. I spent two weeks with a musical director.” But on the eve of her audition to sing at the Village Vanguard in New York she says, she decided to go home instead. She had been to a party in New York: “I found myself in a room filled with people who were using marijuana. I had never seen it. And I decided then that wasn’t the world for me. I went home.”

Soskin only sings now, she says, when she’s asleep: “I remember every line of everything in my dreams.”

In an age when longevity is prized, how does she feel about living so long? “I think it’s given to us. I don’t know that I could have controlled what I’m doing or how I’m living. I just – I don’t. I think it’s a gift. I don’t know where it will lead or where it’s going to take me. I have no idea. Except it’s off. It’s running free.”

• Tell us: has your life taken a new direction after the age of 60?