At aged 50, Susie Martin has already undergone her fair share of health procedures. She has endured dozens of surgeries - once going through five procedures in a single year - and will need to have screening for the rest of her life.

She believes it’s all because of a drug her mother was given by medics during pregnancy.

Ms Martin is one of the hundreds of victims of a “silent scandal” involving the pregnancy drug diethylstilbestrol - a synthetic form of the female hormone oestrogen, commonly known as DES, which has been linked to cancer. Like many others, she says the drug, also known as DES, caused her to develop a lifelong gynaecological condition. She now lives in fear for her health, facing tests each year to ensure she hasn’t developed cancer.

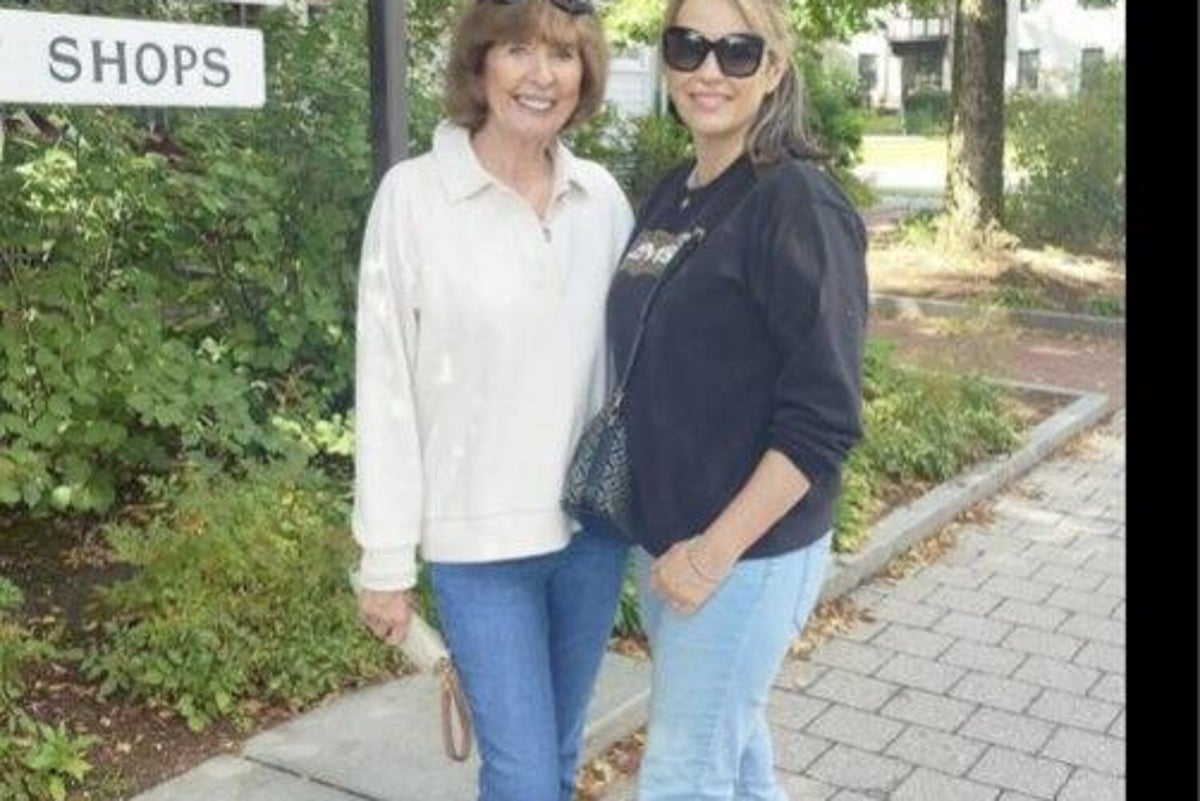

A campaign group of more than 300 people, including Ms Martin and her mother Jennifer Bradley, is calling on the government to launch a public inquiry to address what it describes as a national scandal.

With more than 300,000 having been given DES before it was banned in the UK, campaigners have compared the scandal to Thalidomide, which resulted in thousands of children being born with defects.

Clare Fletcher, partner at the Broudie Jackson Canter solicitors, which represents the group, said: “This is the silent scandal, with victims suffering in pain for decades with limited medical support and no government recognition for what they have been through.

“It is one of the most devastating pharmaceutical failures in UK history and the people whose lives have been marred by it deserve answers.”

She called on the government to “take responsibility” for mistakes of the past and set up a statutory public inquiry to into how the scandal happened and how it was able to be covered up.

She added: “It is a national disgrace that victims have been ignored, disbelieved and humiliated when all they wanted was fair treatment. It is crucial that these sufferers are finally given the truth and afforded access to the compensation they deserve.”

DES was prescribed to pregnant women from 1940 to the 1970s to prevent miscarriage, premature labour and complications of pregnancy.

It was also used to suppress breast milk production, for emergency contraception and to treat menopausal symptoms in women.

In 1971, researchers linked DES exposure to a type of cancer of the cervix and vagina called clear cell adenocarcinoma, prompting US regulators to say the drug should not be prescribed to pregnant women.

However, DES, which is also linked to other cancers such as breast, pancreatic, and cervical, continued to be prescribed to pregnant women in Europe until 1978.

‘Sleepless nights’

Jennifer Bradley, 82, was prescribed DES in 1968 when she was pregnant due to the risks of her having a miscarriage.

After having a miscarriage, she was prescribed the drug again in 1970 when she was pregnant with her daughter, Susie Martin.

In 1974, after watching a TV programme which showed that daughters of women who had taken DES were developing cancer, Ms Bradley asked her GP about the concerns. Her doctor, she says, dismissed them.

“I didn’t take it lightly. I asked questions about it because of the Thalidomide thing in the 50s, and I was assured it was safe. This doctor refused to even look at my medical records. He sent me off.”

Ms Bradley told The Independent about the shock of being asked by her daughter in the 1990s if she had taken the medication after she was diagnosed with adenosis in 2000.

“I was so shocked, and I felt so guilty. She’s always tried to protect me from it, but she’s had to have so many intrusive procedures. It was terrible,” she said.

Since her diagnosis, Ms Martin has had to have between 20 and 30 surgeries. She will have to undergo screening for the rest of her life.

“I’ve had this big weight hanging over me all the time,” she said. “It does have a huge impact; you always worry the diagnosis will come back worse than last time.

“There was physical pain as well as emotional pain. It’s caused sleepless nights, time off work, and time away from my children.”

‘National scandal’

Hundreds of drug companies made DES around the world, and it was marketed under numerous brand names, which makes holding firms liable difficult. It was never patented and was cheap and easy to produce.

Compensation schemes have been set up for DES victims in the US and the Netherlands, but the UK does not have one.

“There’s been no justice at all. There’s been a lot of support worldwide, but there’s been nothing in the UK,” Ms Martin told The Independent. “It’s a national scandal and it’s very frustrating but I’m hoping [the government] will put it right.”

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) told the PA news agency that correspondence was sent by the Committee on Medicines Safety (CSM) in 1973 to inform UK doctors of a US study into instances of vaginal adenocarcinoma.

This advised that no similar cases had been found in the UK, and the letter did not explicitly contraindicate the use of DES in pregnancy and pre-menopausal women.

A spokesman said: “We apologise for this error and for any distress caused to patients and the public.

“At the time of the communication in 1973, usage in pregnancy in the UK was considered to be much lower than in the US which, coupled with the lack of UK cases of affected children, led to the conclusion that communicating to doctors on the available evidence was sufficient.

“This position was supported by the September 1972 CSM minutes, which show the Committee agreed that no action was necessary beyond continued surveillance, as there was no evidence the US findings applied in the UK.”

Later, in 1981/82, Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry datasheets said DES was specifically contraindicated in pregnancy or for women who might become pregnant.

The MHRA said its sympathies lay with those affected by DES, adding: “The committee’s work predates the existence of the MHRA, when medicines vigilance was only in its infancy and there were no electronic records or systematic monitoring of prescriptions.

“There has been a step change in reporting and record keeping since this time and today’s regulatory frameworks are significantly different.”

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: “There are harrowing accounts of harm caused by the historic use of DES, with some women still suffering from the associated risks of this medication which have been passed down a generation, and not feeling adequately listened to or supported.

“The Secretary of State has been clear that he has been looking seriously at this legacy issue and carefully considering what more the government can do to better support women and their families who have been impacted.

“As a result, he has asked NHS England to urgently work closely with local cancer alliances to make sure that GPs are aware of the follow-up guidance for those exposed to DES, so that those who could benefit from additional screening aren’t missing out.”

The new DES Justice UK group has been formed following a year-long ITV News investigation. It is made up of women who took the drug, but also their daughters, sons and granddaughters who have suffered medical issues such as infertility, reproductive abnormalities and increased risk of cancer.

Hundreds of victims of ‘silent scandal’ pregnancy drug call for public inquiry

Scale of workplace violence and abuse ‘shocking and unacceptable’, says charity

‘Faster progress needed’ for Briton who has spent eight years in Indian jail

Tax rises at Budget ‘inevitable’, think tank with close Labour links claims

‘Poisoned’ woman exposed to drug feared she could never have children

The common drug that can reduce side effects for cancer patients