On June 7, 1195, a “marvelous sign” appeared in the sky near London. Storm clouds gathered over the River Thames, and a glowing white ball of light dropped from the base of the clouds. It hovered there for a moment, spinning, before dropping toward the river and moving sideways. The account, written down by a monk named Gervase of Canterbury in around 1200, sounds bizarre – but it’s an eyewitness description of a real weather event, according to historian Giles Gasper and physicist Brian Tanner, both of Durham University.

In his chronicles of daily life at Christ Church Cathedral Priory in Canterbury, England, the chronicler Gervase apparently recorded one of the earliest known descriptions of a rare weather phenomenon called ball lightning. Gasper and Tanner recently published their conclusions in the Royal Meteorological Society journal Weather.

Great Balls of Fire

Lightning strikes somewhere on Earth about 3 million times a day. The constant motion of water droplets inside a storm builds up a negative electrical charge at the base of the cloud. When the negative charge gets strong enough, it suddenly discharges to the positively-charged top of a cloud or to a spot on the ground. For about 1/5 of a second, a single bolt of lightning blazes 5 times hotter than the surface of the Sun. The superheated air swells so rapidly that it makes a booming sound: thunder.

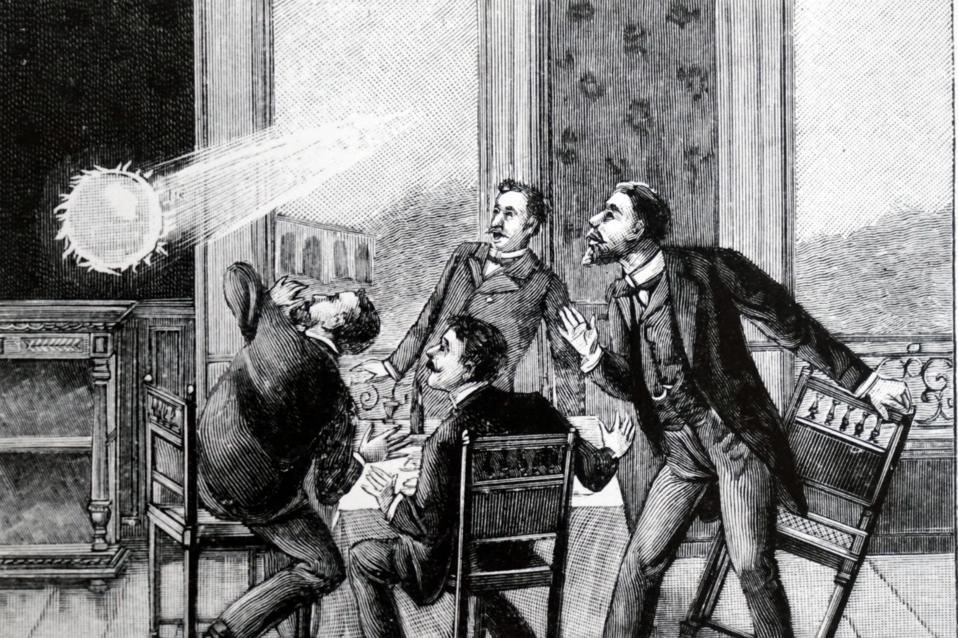

Ball lightning is different and much rarer than the familiar lightning bolts that flash across the sky and vanish in a fraction of a second. Picture a fireball a few centimeters wide; it hovers, flies horizontally, or darts around erratically for several seconds. Now imagine that it reeks of sulfur.

Historical accounts describe ball lightning sweeping across the decks of ships, bursting through windows, blasting off people’s limbs, and setting buildings on fire. In the past, people often interpreted these fireballs from the sky as supernatural omens, and today they sound like excellent fodder for a sci-fi/horror movie script, but ball lightning is a totally natural phenomenon with a physical cause – even if scientists don’t yet agree on what that physical cause is.

This strange phenomenon is so rare that it’s difficult to get good scientific data. Much of what we know about ball lightning, including the conditions under which it forms and how it behaves, still comes from eyewitness reports, which aren’t always reliable and don’t always include the kinds of details scientists need to answer important questions like “Exactly why the heck is this thing happening?”

A group of physicists managed to measure the spectrum of a ball lightning fireball in China in 2012. A spectrum is breakdown of all the wavelengths of light emitted by an object, which usually correspond to the chemicals it’s made of. The 2012 fireball’s spectrum looked like what you’d expect to see if a handful of soil got vaporized by intense heat. According to physicist Ping Yuan of Northwest Normal University in Lanzhou, China, that supports the idea that ball lightning may happen when a normal cloud-to-ground lightning strike vaporizes soil.

However, that’s not enough data to say for certain that ball lightning is made of plasma from soil vaporized by lightning. It also doesn’t explain exactly what conditions are necessary for the fireballs to happen or why they move the way they do. Other teams of researchers have produced something very similar to ball lightning in lab experiments, but it still hasn’t provided definite answers.

“Modern technology allows us to observe our weather in more detail than ever before and understand with greater depth. Ball lightning, however, remains elusive, and it’s the subject of many theories,” said BBC Weather’s Susan Powell. “It’s interesting to think that in this respect, despite our advances, we stand as mystified as observers in the 12th century.”

Because we understand so little about ball lightning, and because it’s so rare and hard to observe, every scrap of detail from a sighting is potentially useful. Every eyewitness description provides another data point about the conditions under which ball lightning forms, how long it lasts, and how it behaves. That’s true even when the descriptions are hundreds of years old.

“We should not dismiss medieval descriptions of the natural world as being mired in superstition and therefore of no value,” Tanner told the BBC. In fact, modern scientists have gleaned useful data from ancient and medieval descriptions of astronomical events like eclipses, comets, and supernovae; geological events like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions; and meteorological events like storms and, apparently, ball lightning.

A Marvelous Sign

Gervase of Canterbury is as reliable a witness as modern scientists could hope to find in the late 12th century. His Chronicles mostly focus on the legal and financial goings-on at the priory, but he also mentioned earthquakes, interesting weather, and celestial events. Astronomers have previously turned to Gervase’s descriptions of lunar eclipses and an asteroid striking the Moon. He had a good eye for detail, even if the modern reader has to filter that detail through distinctly medieval turns of phrase.

According to Gervase, something extraordinary happened around midday on June 7, 1195.

“For the densest and darkest cloud appeared in the air, growing strongly with the sun shining brightly all around,” he wrote.

A bright white light formed at the base of the cloud, and then “that, growing into a spherical shape under the black cloud, remained suspended between the Thames and the lodging of the bishop of Norwich. From there, a sort of fiery globe threw itself down into the river. With a spinning motion, it dropped time and again below the walls of the previously mentioned bishop’s household.”

Tanner and Gasper compared Gervase’s description to other historical and modern reports of ball lightning, and they’re convinced.

“It is fascinating to see how closely Gervase’s 12th century description matches modern reports of ball lightning,” Tanner told the BBC. “There are even videos on the internet that show some of the effects he was describing.”

Gasper calls Gervase’s Chronicles “the first fully convincing account of ball lightning anywhere.” Is it really the first, though?

Saints And Omens

The Roman Empire’s domination of western Europe ended shortly before Gregory of Tours was born around 538 CE, but life in southern France at the time was culturally still very Roman. He lived in a very different world from the later medieval monk Gervase, but both men were members of the Christian clergy; Gregory eventually became a bishop and a saint. And like Gervase of Canterbury, Gregory of Tours seems to have written about ball lightning.

In his Historia Francorum – a long and detailed history of the early kings of the Franks – he mentions that during a rainstorm, “a great ball of fire fell from the sky and moved a considerable distance through the air, shining so brightly that visibility was as clear as at high noon.” The fireball eventually vanished behind a cloud.

With the benefit of hindsight, Gregory of Tours interpreted the fireball as an omen, which he thought had predicted the death of a French prince (according to ScienceAlert’s Mike McRae).

Historical records like Gervase of Canterbury’s Chronicles and Gregory of Tours’ Historia Francorum can provide valuable information to modern scientists, but ancient writers seldom knew what caused the phenomena they saw, and they seldom used the same terminology as modern scientists (or even other ancient ones). That leaves a lot of room for debate about what writers like Gervase and Gregory meant by phrases like “a great ball of fire fell from the sky.”

Regardless of which medieval cleric gets to claim the title of World’s Oldest Ball Lightning Report, however, modern science still has a fascinating mystery to solve.