From New York City to Duke of York Island in Antarctica, the Dukedom of York has a wider cultural resonance than you might immediately realise.

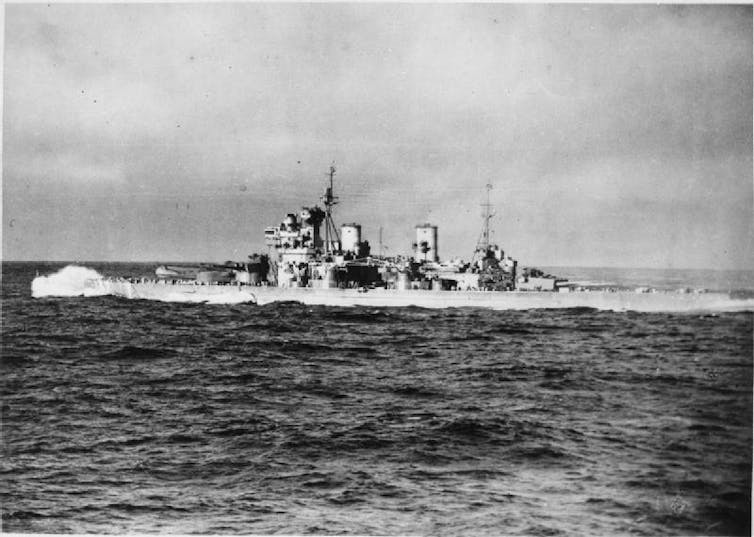

The Duke of York military slow march can often be heard ringing out during the Changing the Guard in London and one of the city’s best-known theatres carries the name. The same is true for pubs in places like London and Belfast, and a second world war battleship and a passenger steamer share the same name too.

Equally, the holders of the title Duke of York have, for over six centuries, held a prominent position in British royalty and society. Customarily conferred on the second son of the reigning monarch, this dukedom has been closely associated with being the “spare to the heir” – the brother born to support the crown rather than inherit it.

Close to the sovereign but destined for a different journey, the story of the dukes of York is one of privilege and dutiful service, with a liberal peppering of scandal and twists of fate.

The current holder of the dukedom, Prince Andrew, has agreed to no longer use the titles and honours conferred upon him – the first time this has happened in the dukedom’s history.

This is a long history of men whose lives were shaped by their unique position within the monarchy. Proximity to power without possession may be the defining factor, but the dukes of York more often than not actively or accidentally flip that rule on its head – almost half of these “spares” found themselves becoming king, one way or another.

There have been 11 men officially styled Duke of York and three holders of the title Duke of York and Albany – a fusion of two titles, one from Scotland and one from England, devised as a demonstration of unity following the 1707 Act of Union.

Edmund of Langley was the first duke, after being granted the title by his father Edward III in 1385. He is the Duke of York who appears in Shakespeare’s Richard II, a play named after the duke’s nephew and son of Edward, the Black Prince.

Following the legal principle of male primogeniture, Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, inherited the title upon his father’s death in 1402. Edward was killed at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 and, without children, the title passed to his nephew Richard of York – 3rd Duke of York.

Richard’s death in battle in 1460, during the War of the Roses, then left the title to Edward Plantagenet. When Edward won the Battle of Towton in March 1461, subsequently becoming Edward IV, the Dukedom of York merged with the crown and became extinct, bringing a close to the 76-year existence of this first iteration of the title.

Incredibly, these are the only examples of the title being inherited. In over 560 years since, no Duke of York (or Duke of York and Albany) has ever directly passed the title to a legitimate heir. Of the subsequent ten men bearing either title, four died without heirs, five found themselves as heir to the throne following the death of their elder brother (or his abdication, as happened in 1936) and then king. And in Prince Andrew’s case, without a male heir – having had two daughters.

The duke who disappeared

Edward IV – himself a former Duke of York, recreated the dukedom for his second son, Richard of Shrewsbury, thus starting the long association of this title with the second-born son. Richard was married at the age of four and was one of the Princes in the Tower who disappeared and was presumed dead in 1483 aged 9.

The dukes who became kings

The title was revived in 1494 for Henry Tudor but again died out when Henry Tudor became King Henry VIII (1509). The same happened to Charles Stuart, who was given the dukedom in 1605 but also became king (Charles I, 1625).

James Stuart, second son of Charles I, was technically Duke of York from birth, but this was formalised in 1644. In 1660, James was granted the parallel Scottish title of Duke of Albany. New York state, its capital Albany, and New York City derive their names from this duke. James succeeded his childless brother Charles II and became James II of England and James VII of Scotland in 1685, when the title merged with the crown. James was later deposed in the 1688 revolution.

In 1892 Queen Victoria bestowed the title on her grandson, Prince George, the second son of the Prince of Wales and future Edward VII. However, this creation came following the death of George’s older brother. He became George V (1910) and the title merged with the crown.

George made his second son, Prince Albert, Duke of York in 1920. Initially more than comfortable being in the shadows of his elder brother Edward VIII, the abdication crisis of 1936 – the year of three kings – unexpectedly saw Albert become George VI. Because of this duke, the future Queen Elizabeth II was initially styled “Princess Elizabeth of York”.

Three double dukes

Although the dukedoms of York and Albany have been simultaneously held by the same person at times, three men have held the unified “double dukedom” as Duke of York and Albany in the 18th century, yet all died without heirs.

They were Ernest Augustus of Brunswick-Lüneburg, who served in the nine years’ war and the war of the Spanish succession, Prince Edward, who was briefly heir-presumptive, and Prince Frederick Augustus, second son of George III.

This Duke of York served a lengthy period as commander-in-chief of the British Army, including during the Napoleonic wars. He is perhaps the most likely inspiration for the “Grand Old Duke of York” rhyme. He is also memorialised on the Duke of York Column where Regent Street meets The Mall in London.

Queen Victoria again separated these titles, creating her fourth son, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany in 1881, and her eldest grandson Duke of York in 1892.

Andrew became Duke of York in 1986 when he married Sarah Ferguson. While he has agreed to no longer be styled as such, he technically has not been stripped of the title. Nevertheless, with no male heir, the dukedom will become extinct upon his death, regardless.

Although it could be assumed that the title would have been recreated for Prince Harry as the second son of King Charles III, his self-imposed exile and ongoing controversies mean that the future of the Dukedom of York remains uncertain. Perhaps the next revival will take some consideration.

Mark McKinty does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.