On the outskirts of Jaipur, in a village named Machwa, an 86-year-old Dalit widow lives in a cluster of makeshift jhuggis. The settlement is built from uneven brick walls and patched with tarpaulin sheets and rusted tin roofs. Inside, her family of nearly 30 – sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren – sleep on thin mattresses spread directly over the hard earth.

Santra Devi works as a midwife and her sons as daily wage construction workers, while their wives scrub floors and wash utensils in other people’s homes. Despite all of this, there are days when the family goes to sleep on empty stomachs.

Santra Devi says they ended up here after being “forced off” their 2 bighas of ancestral land after her husband died in 2013. She says the land, strategically located near the Jaipur-Jodhpur Mega Highway, was taken away by builders, politicians and cooperative housing societies – with the backing of the local administration – and that she’s been fighting to get it back ever since.

“Jab tak dum hai, ladna hai,” she says. (As long as I have strength, I have to fight.)

Santra Devi’s story is far from unique. A Newslaundry investigation identified at least 125 similar cases – of Dalit and Adivasi families alleging their agricultural land was taken away – in the last 60 years. All these cases have reached the Rajasthan High Court. Together, they span 637 acres of agricultural land.

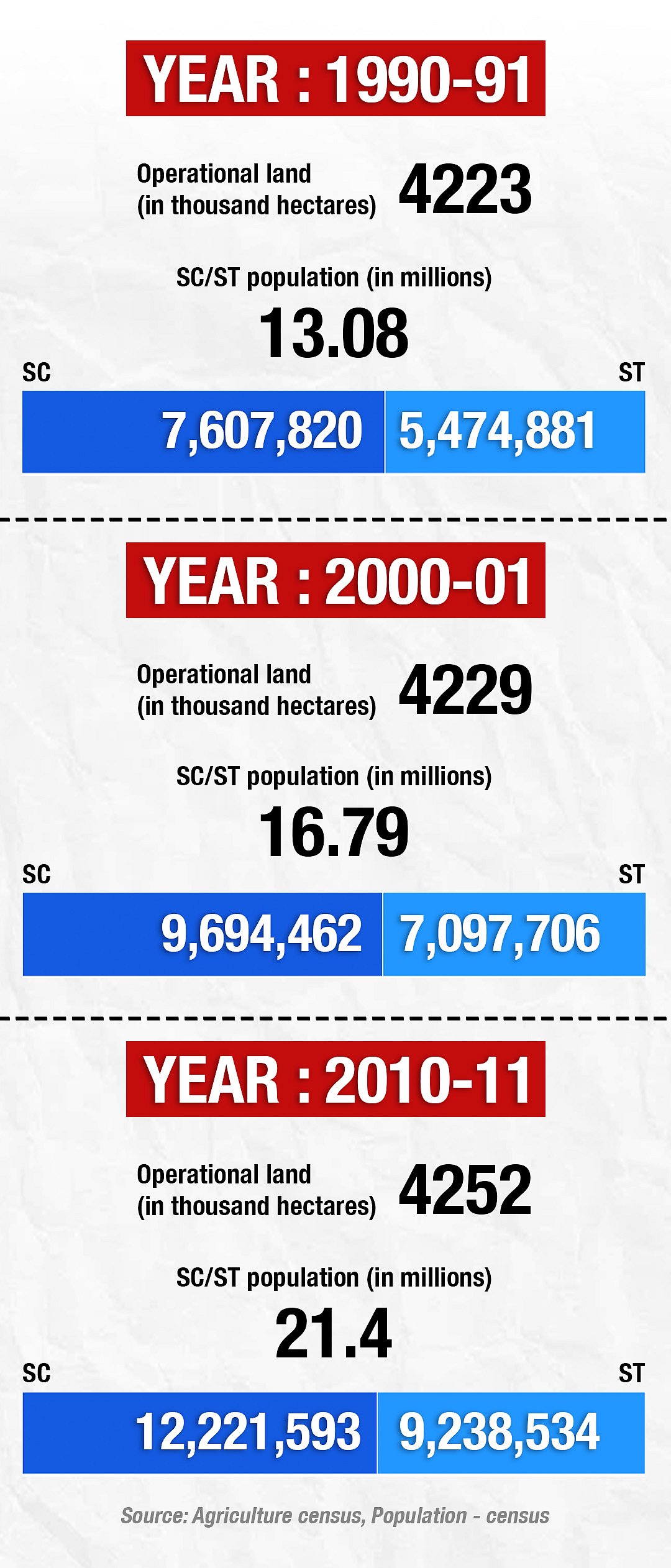

And here’s a startling statistic: Between 1990 and 2010, the Dalit-Adivasi population in Rajasthan grew by 63 percent. In the same time period, the farmland they collectively own grew by less than one percent.

This despite multiple legal protections meant to safeguard land belonging to Dalit and Adivasi communities in the state. For instance, Section 42 of the Rajasthan Tenancy Act of 1955 clearly states that any sale, gift or transfer of agricultural land by an SC or ST khatedar, or landowner, to a non-SC/ST individual is legally void.

Yet Newslaundry’s investigation found that these safeguards are systematically undermined or violated across Rajasthan. We examined court records, land records and interviewed families to find that Dalit and Adivasi landowners are being deliberately targeted. Their records are tampered with, and legal protections are sidestepped. Ownership is transferred through forged documents, backdated entries, coercive deals, or procedural loopholes.

These point to a seeming collusion between builders, cooperative societies, revenue officials and, at times, the inaction – or complicity – of the local police.

Of the 125 cases we counted, over 42 percent involve land located in Jaipur, Alwar, Sikar, Ajmer, Tonk and Dausa.

We additionally examined two cases on the ground which were located along the Jaipur-Jodhpur mega highway and the Delhi-Jaipur-Ajmer expressway, respectively. This location is important: Over the last few years, the commercial value of these stretches have surged; builders claim prices have risen by 65 to 98 percent. With the rapid urbanisation of Jaipur and its outskirts, these highways are lined with large billboards from prominent builders advertising both existing and upcoming residential and commercial projects.

And given that these routes connect the state capital to major cities like Delhi, Ajmer and Jodhpur, the Dalit-Adivasi plots in these areas are especially vulnerable to builders and local strongmen looking to make a killing.

This is how they do it.

Between 1990 and 2010, the Dalit-Adivasi population in Rajasthan grew by 63 percent. In the same time period, the farmland they collectively own grew by less than one percent.

I: Cooperative housing societies

Most commonly found in our investigation was the use of cooperative housing societies as vehicles to facilitate land grab, often enabled by the weak regulatory framework of cooperatives in Rajasthan.

A cooperative housing society is a legal entity that purchases land, develops it into residential complexes or flats, and then sells or allots them. Local NGOs said these societies are often run by builders, politicians or influential locals as vehicles to facilitate land grab. Newslaundry learned that the societies are accused of forging sales deeds and backdating documents to purportedly take over ownership of land belonging to Dalit and Adivasi families.

Of the court records we scrutinised for the 125 cases and the two cases we investigated from the ground, we identified multiple cooperative housing societies that were accused of land grab. We decided to look at four – the Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti, New Pink City Nirman Sahakari Samiti, Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari and Ganpati Grih Nirman Sahkari Samiti – a little closer.

The Ganpati Grih Nirman Sahkari Samiti is run by Rajendra Kedia, the founder of Kedia Builders and Colonizers. Kedia served as the Samiti’s chairperson from 1989 to 1997 and again from 2001 to 2019.

Kedia wields significant influence, in part due to his political ties. He joined the Aam Aadmi Party in 2023 and became the party’s state senior vice-president four days later. His son Saurabh is married to the daughter of Sitaram Agarwal, a former Congress leader who joined the BJP in 2024. Saurabh was previously the director of the Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation.

Newslaundry accessed over six FIRs and istagasas from Jaipur and its outskirts that claim Kedia and the Samiti are involved in land grab, fraud, forgery, criminal conspiracy and kidnapping. (An istagasa is a criminal complaint filed before a magistrate, often when the police refuse to register an FIR or fail to act.)

One of these cases involves Mukesh Meena, an Adivasi man in Machda village on the outskirts of Jaipur. For the past two years, Mukesh has been fighting to reclaim 2.85 acres of his family’s farmland, located less than two km from the Delhi-Jaipur-Ajmer expressway. The land originally belonged to his grandfather and was inherited by his father.

Mukesh’s extended family owns a total of 24 bighas near the highway. He alleges that Kedia, acting through the Samiti, bought nearly 20 bighas of land from his relatives and that a large settlement, Balaji Vihar 29 Colony, has been constructed on this land, housing hundreds of families. All this, he said, in violation of Section 42.

Newslaundry could not corroborate Mukesh’s allegations.

Mukesh also told this reporter that his father didn’t sell his share of land, measuring approximately 4 bighas and 11 biswas. He claims that in 2024, the Samiti purportedly submitted a fake ikrarnama, or agreement, before the Jaipur Development Authority. This ikrarnama was purportedly signed in 1995, and the Samiti used it to establish control over the plot. With this, Mukesh alleged, the Samiti now owned all 24 bighas of his family’s land.

Newslaundry reviewed the ikrarnama in question, dated May 1995, and other documents. We found two major red flags:

- The agreement cites certain khasra numbers which, according to government records obtained through an RTI response from the tehsildar’s office, were assigned only on March 31, 1998 – nearly three years after the date on the ikrarnama. In 1995, the same parcels of land carried an entirely different set of khasra numbers.

- Until 2013, Mukesh’s family continued to receive compensation from the government for crop losses – a benefit given only to recorded landowners. This suggests that official land records still recognised the Meenas, not the Samiti, as lawful owners.

In November this year, Newslaundry visited the site where Mukesh’s father once owned land. We saw signboards saying “Court Stay – ACJ-17 Chomu Case No. 63/24 – Ramswaroop Meena Vs Rajendra Agrawal (Ganpati Grih Nirman Sahkari Samiti)”. Rajendra Agrawal is the name Kedia uses in official documents.

We also found four buildings – walled structures without finished roofs – and a few others under construction. A handful of families lived in these partial structures, but they did not speak to this reporter. Mukesh claims these structures were “built covertly at night” and that construction continues to take place despite repeated complaints to the police.

We then asked Rakesh Kedia about all the allegations against him. He said, “See, making accusations and proving them in court are separate things. All the Meena brothers have submitted documents in court stating that their father had sold his land to me. Now, this dispute is between the brothers and I am not even involved in the case.”

We also sent Kedia a detailed questionnaire. This report will be updated if he responds.

We sent questionnaires to Sub-Inspector Ramavatar Nayak (the investigating officer in the Meena case), Patwari Amar Singh, and Tehsildar Ramchandra Gurjar.

Nayak declined to speak.

Singh denied going to the disputed land to make any inspection. He said, “The matter is with the court. Patwari has no role in it.”

Gurjar said, “I am not posted there anymore. I cannot recall this case.”

Until 2013, Mukesh’s family continued to receive compensation from the government for crop losses – a benefit given only to recorded landowners. This suggests that official land records still recognised the Meenas, not the Samiti, as lawful owners.

Another major cooperative housing society that we examined is New Pink City Nirman Sahakari Samiti, which was accused in at least two out of 125 cases.

In one such case from 1982, the Rajasthan Housing Board acquired a Dalit family’s land for a public housing project and offered compensation to the family. The New Pink City Nirman Sahakari Samiti claimed that the Dalit landowners had sold their land to it back in 1974, and that it was therefore entitled to receive either the compensation or share in the developed property.

The Rajasthan High Court rejected this demand, saying the Samiti’s so-called sales agreement had no legal validity under Section 42. Hence the society cannot assert any right to compensation or allotment.

The other two societies, Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samit and Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari, are both accused in Santra Devi’s case of using forged documents to grab her land.

We reached out to Anup Kumar Sen, Chairperson of Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari, and Mahavir Yadav, former Chairperson of the now-disbanded Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti, for their responses to the allegations. Sen and Yadav declined to comment.

II: Exploitation of loan defaults by Dalits and Adivasis

Across the 125 cases under scrutiny, we spotted this pattern in at least eight cases: the use of loan defaults to dispossess Dalit and Adivasi farmers of their land.

Typically, if a farmer falls behind on repaying loans, their land is auctioned off by the bank to recover the loans. But in the case of Dalit and Adivasi farmers, the high court has repeatedly ruled such sales to be void under Section 42.

In 1971, for example, Badri Lal Raigar, a Dalit farmer from Malpura in Tonk district, took a loan of Rs 4,500 from the Tonk District Cooperative Land Development Bank. He defaulted on the loan and the bank auctioned his property, selling it to a non-Dalit in 1985. The matter reached the high court which quashed the auction as ‘void’. The court said the transfer of SC/ST land to a non-SC/ST party is legally invalid under Section 42 regardless of the circumstances of the transfer.

Yet we identified eight cases in which this happened. These cases reached the high court after years, often decades, of being pushed through patwaris, tehsildars, sub-divisional magistrates, collectors and civil courts.

In one case in 2010, an Adivasi farmer from Jalore mortgaged his land to take a loan from the Land Development Bank. He failed to repay it. The bank then auctioned his land to a non-Adivasi party. The matter went to the high court where a single judge initially held that Section 42 didn’t apply to auction sales. However a full bench later held that Section 42 applies to all forms of transfer, including bank recovery auctions.

In another case from Jalore, the Bhumi Vikas Bank in Raniwara auctioned land belonging to Janu, a Scheduled Tribe cultivator. Courts later ruled the transfer void because the auction purchaser was not from an ST community.

In at least two other cases, authorities acting under the Rajasthan Agricultural Credit Operations (Removal of Difficulties) Act, 1974 were found to have auctioned land originally owned by Dalit or Adivasi farmers.

Comparable violations have been recorded involving the Jodhpur Sahakari Bhumi Vikas Bank, the Chittorgarh Primary Cooperative Land Development Bank, and the Co-operative Land Development Bank. In almost all cases, the high court or Board of Revenue later declared most of these sales void.

It’s worth noting that in 2020, the Ashok Gehlot government passed a bill to prevent the auction of up to five acres of agricultural land. Intended to stop banks from seizing land to recover loans, the bill stalled while awaiting approval from the President and the Governor. The state then issued an administrative order in January 2022 to halt auctions, but the bill itself remains unapproved.

Satish Kumar of the Centre for Dalit Rights said, “Across Rajasthan, we see a clear pattern: even modest or partially repaid farm loans can escalate to the point where banks move to auction farmland – often the family’s only secure asset. The consequences are devastating for poor Dalit and Adivasi households, raising urgent questions about the fairness, oversight, and human cost of current loan-recovery systems.”

Typically, if a farmer falls behind on repaying loans, their land is auctioned off by the bank to recover the loans. But in the case of Dalit and Adivasi farmers, the high court has repeatedly ruled such sales to be void under Section 42.

III: Benami transactions

A pattern that surfaced more than once in our investigation was the use of benami transactions to capture land belonging to Dalit and Adivasi families.

Local NGOs told Newslaundry that these deals are purportedly fronted by low-level employees, associates or brokers, purportedly acting as proxies for powerful local actors such as sarpanches, strongmen and private builders. By routing transactions through these intermediaries, the real beneficiaries reportedly conceal their identities and evade legal safeguards, particularly the protections under Section 42.

Santra Devi’s story is one such case. The land was originally owned by her husband Bhairu Lal who died in 2013.

She says her family was “pushed off” their ancestral land by local strongmen who had ties to the village sarpanch Lal Chand Sehrawat. Sehrawat allegedly set her house on fire in 2015. He died in 2020 and his nephew Rajendra purportedly sold Santra Devi’s land to two cooperative societies: Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti and Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti.

The land is currently fenced off, with a concrete road-like structure built on a portion of it. There are also about 21 shops; some of the owners told Newslaundry that they’re aware their shops might be demolished since the land might be developed into a housing project by Kedia Builders and Colonizers.

Locals told us that the cooperative societies had sold the land to two individuals – one said to be a Kedia employee and the other described as a broker associated with him. Both are purportedly benami buyers, who now own the land to purportedly allow Rajendra Kedia to assume control over it.

Newslaundry could not independently verify these details. However, we did look at two ikrarnamas through which the societies claimed to have bought the land. (It should be noted that the original ikrarnamas can’t be traced; official documents only rely on their photocopies.)

Local NGOs told Newslaundry that these deals are purportedly fronted by low-level employees, associates or brokers, purportedly acting as proxies for powerful local actors such as sarpanches, strongmen and private builders.

Here’s what we found in Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti’s ikrarnama, dated April 15, 1997:

1) The buyer – the chairperson of the society – is not mentioned anywhere in the document. An ikrarnama is ordinarily expected to contain the names and signatures of both the buyer and the seller, but this document does not include the buyer’s name or signature.

2) The document bears the signatures of Bhairu Lal’s children as sellers. Of the nine children who signed it, five were minors at the time of signing. Additionally, a son named Ravi has an Aadhaar card that indicates he was only born in September 1997, five months after his signature appeared on the document.

Advocate Kartik Venu said this is odd. “If the original and sole owner of a property is alive and of sound mind, neither their children nor any other person can execute a sale deed on their behalf unless they have been formally authorised to do so,” he said. Bhairu Lal was alive when the ikrarnama was signed and Santra Devi confirmed to Newslaundry that her children were not authorised to sign the sales deed on their father’s behalf.

Here’s what we found in Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti’s ikrarnama, dated December 1995:

1) The document carries Bhairu Lal’s signature. But his family said he was illiterate and only signed using a thumb impression. He wouldn’t have written his name.

2) The document lists Subhash Kumar Meena as the Samiti’s chairperson, and carries his signature. Meena’s own Aadhaar card says he was born in 1980, so he would have been a 15-year-old minor at the time. Also, the Samiti’s official documents indicate that one Suresh Kumar Jain was chairperson then – so why didn’t he sign the document?

We reached out to Rajendra Kedia of the Ganpati Grih Nirman Sahkari Samiti, as well as Anup Kumar Sen, Chairperson of Sirohi Grih Nirman Sahakari, and Mahavir Yadav, former Chairperson of the now-disbanded Vijaypura Grih Nirman Sahakari Samiti, for their responses to the allegations.

Kedia denied all accusations, stating, “I have nothing to do with Sanara Devi's land. I only purchased the adjacent land.”

Sen and Yadav declined to comment.

For the purposes of this story, we were only able to look at 125 high court cases, and they cannot begin to present the full picture. Most encroachment disputes involving agricultural land are adjudicated in revenue courts. Activists told us that too many cases don’t even reach the stage of a police FIR.

“In most cases we have encountered, the police either refuse or show reluctance to register FIRs,” said Tolaram Chauhan, who works with an NGO called Unnati in Barmer. “Instead, the officers either push for a compromise between the parties or direct the complainants to approach the sub-divisional magistrate’s court.”

At least two SC/ST families told this reporter that the police refused to register FIRs after they complained of land encroachment.

Satish Kumar, a lawyer and director of the Centre for Dalit Rights (Dalit Manavadhikar Kendra Samiti) in Jaipur, said he has handled several cases of land grab in Rajasthan, where he represents the families.

“In Rajasthan, because the law prohibits direct purchase of SC/ST land by non-SC/ST, the builders, co-operative housing societies and local strongmen often turn to deceptive, illegal and fraudulent methods to grab land belonging to Dalits and Adivasis,” he said. “These methods range from manipulating government records to using proxies, and exploiting government corruption.”

Requests for comment

For this story, we reached out to a wide range of officials and authorities for comment on the allegations and administrative actions referenced in this report, including Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma; Deputy Chief Minister and Finance Minister Diya Kumari; Principal Secretary (Finance) Vaibhav Galriya; Secretary, Finance (Revenue) Kumar Pal Gautam; Principal Secretary and Registrar, Co-operative Department, Manju Rajpal; Additional Registrar (II) Sandeep Khandelwal; Jaipur Police Commissioner Sachin Mittal; Jaipur District Collector Dr. Jitendra Kumar Soni; and Hemant Kumar Gera, Chairman, Board of Revenue, Rajasthan.

We also contacted the chairpersons of the National Human Rights Commission, the Rajasthan State Human Rights Commission, the Rajasthan Scheduled Castes Commission, and the National SC/ST Commissions.

Despite multiple attempts, none of these officials responded to our questions or provided a statement at the time of publication.

We sought responses from district-level officers involved in the case. Superintendent of Police Hanuman Meena said the matter is under investigation and therefore he could not comment, though he added that “it is very likely that Santra Devi’s husband would have sold his land.”

Tehsildar Jaipal Singh stated that the matter rests with the District Collector and declined further queries. We attempted to meet District Collector Dr. Jitendra Kumar Soni on two occasions but were not granted an appointment. Patwari Lata Verma, who submitted a report in the Santra Devi case, also declined to speak with us.

This report will be updated if any of the officials or authorities contacted choose to provide a response.

Rajendra Kedia, when questioned about the allegations levelled against him in the Santra Devi and Mukesh Meena cases, denied all accusations, saying the matter is currently before the court and will be decided on its merits. We have also sent him a detailed questionnaire seeking clarification on specific claims. This report will be updated if and when he responds.

The silent erasure of Rajasthan’s Dalit–Adivasi map

Newslaundry analysed the growth of Rajasthan’s Dalit and Adivasi population alongside changes in the agricultural land operated by these communities across three time points: 1990–91, 2000–01 and 2010–11.

Data on operational holdings were taken from the All India Report on Agricultural Census for the respective years, while population figures were drawn from the Census of 1991, 2001 and 2011. These years were selected as they provide the latest available state-wise official population figures for SC/ST communities.

Between 1990 and 2010, the SC/ST population expanded by 63.61 percent. Yet, during the same period, the agricultural land operated by these communities grew by just 0.69 percent — effectively stagnant. In absolute terms, while the Dalit–Adivasi population increased by over 8.32 million between 1990 and 2010, the land they operated rose by only 29,000 hectares during the same period.

On an average, every year the Dalit-Adivasi population expanded about 73 times more than the farmland available to support them.

The consequences are visible in rapidly shrinking land-per-capita. In 1990–91, Dalit–Adivasi communities operated about 0.32 hectares per person. By 2000–01, this had fallen to 0.25 hectares, and by 2010–11, further to 0.19 hectares. Over the 20-year period, this reflects a nearly 40% decline in per-capita access to agricultural land.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.