Even though there is only one true way of how historical events actually unfolded, there sure are many myths and legends that surround them. And while some seem way too far-fetched, others can be quite convincing, which is why they often become rather widely known.

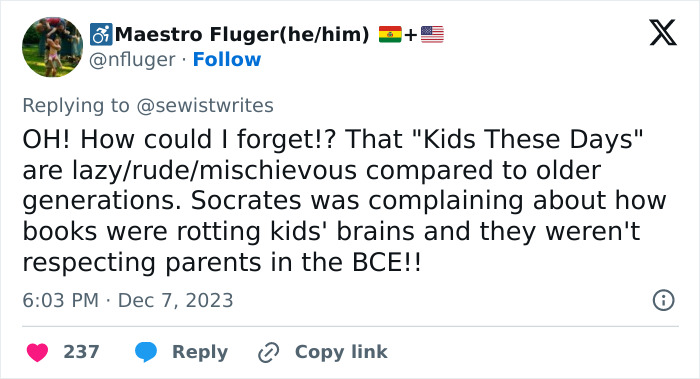

A netizen going by the moniker of ‘sewistwrites’ recently turned to X (formerly Twitter) to learn more about such convincing yet not necessarily accurate historical myths. She shared that the ones that make her hackles rise relate to corsets and romance, this way starting a thread, which covered everything from Columbus to salt, and beyond. Scroll down to find more historical myths shared by the netizens on X and see what other bits of historical information might not be entirely true.

In order to learn more about historical myths and how they can influence the way people view history itself, Bored Panda turned to associate professor of history at Southern Utah University, Dave Lunt, who was kind enough to answer a few of our questions. You will find his thoughts in the text below.

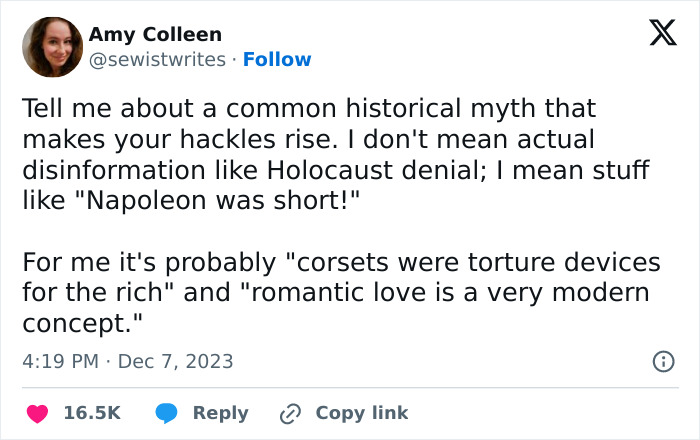

#1

Image credits: SkeelMagnolia

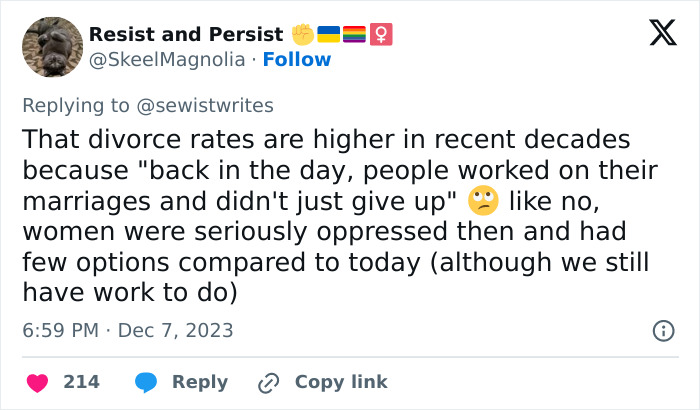

#2

Image credits: DallinStuart

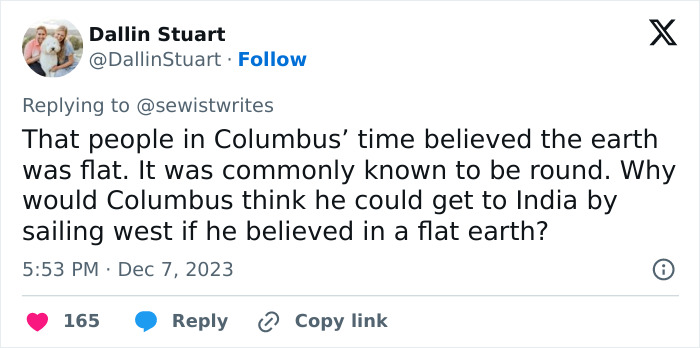

#3

Image credits: nfluger

While for some, history is not much more than a bunch of names and dates, others could spend countless hours studying how certain events developed and how they changed the world we live in now.

“The decisions of people who came before us definitely impacted the world we live in today; just as our decisions will impact the people who come later,” associate professor of history at Southern Utah University, Dave Lunt, told Bored Panda, adding that history is more than just “the things that happened”.

“It’s more of the understanding and interpretation of what happened,” he explained. “Most of the time we can all agree on the basic facts, dates, and events. But history occurs in figuring out the bigger trends or effects of the events in the past. And the most interesting interpretations are usually complicated, nuanced, and firmly situated in ‘the gray areas’.”

#4

Image credits: maggiekb1

#5

Image credits: werewolfnotvamp

Assoc. Prof. Lunt suggested that practicing the skills of investigation and interpretation can help make sense of our world as the years go by. “Oftentimes, very small things end up having momentous consequences in our lives. The first time we meet ‘that special someone’, we rarely understand how momentous that meeting is. The same is true of history. Only later can we appreciate the true value and importance of certain events.”

#6

Image credits: zgryphon

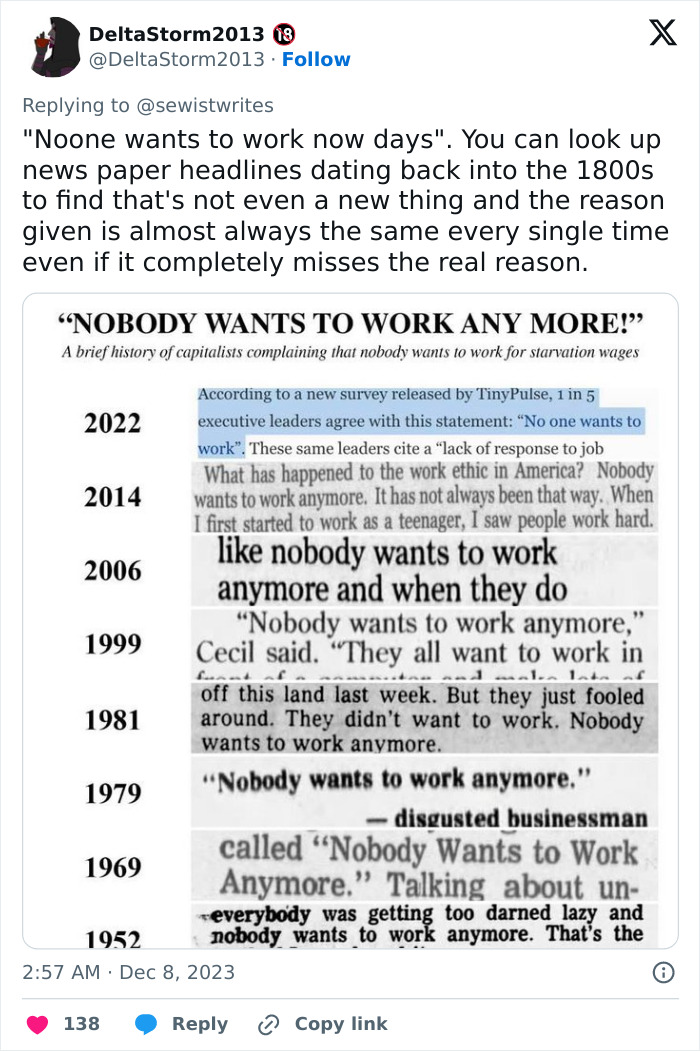

#7

Image credits: DeltaStorm2013

#8

Image credits: hoorayheather

Dave Lunt shared that the idea of cause and effect is what fascinates him the most about history. “I think, in some ways, that history is similar to science in that historians develop theories and then test them against the evidence,” he said.

“But history isn’t science. Sometimes things happen that defy easy explanation. Some things don’t have a rational cause and effect; underdogs can win the big battle, or a freak weather event can alter plans, or an unexpected eclipse of the sun in August, 413 BCE can convince the Athenians to delay an attack on their enemies, allowing the enemies to regroup and defeat them. It is a desire to know more about these human factors in the events of the past that draws me to history.”

#9

Image credits: therealkuri

#10

Image credits: GRMuir22

#11

Image credits: AdrienneRoyer

Unsurprisingly, the general public’s view of history is not exactly the same as those of the professionals in the field. A national survey in the US, conducted back in 2020, found that the majority of respondents—roughly two-thirds of them—consider it to be “an assemblage of names, dates, and events”. (While for practicing historians it’s more of a field that provides explanations for certain events in the past.)

The survey found that the vast majority of people (as many as nine out of ten of them) say that one can learn history everywhere, not just in school. Nearly three quarters believe that it’s easier to learn history when it’s presented like entertainment, which might be one of the reasons why the most popular sources of information for the general public are all in video format.

#12

Image credits: AThrillosopher

#13

Image credits: sailortaiyo

#14

Image credits: chrisnodima

The 2020 survey found that the main sources of historical information for the general public are documentary and fictional movies and television, followed by various online and print sources, and museums, with history lessons and college courses lining up at the end of the list.

Despite being the most popular, though, movies and TV were not considered to be the most reliable sources for historical information. That might be because without certain embellishments or adjustments, some historical events would be too “dry” or too complicated to follow, which, according to Lunt, is one of the likely ways myths are born.

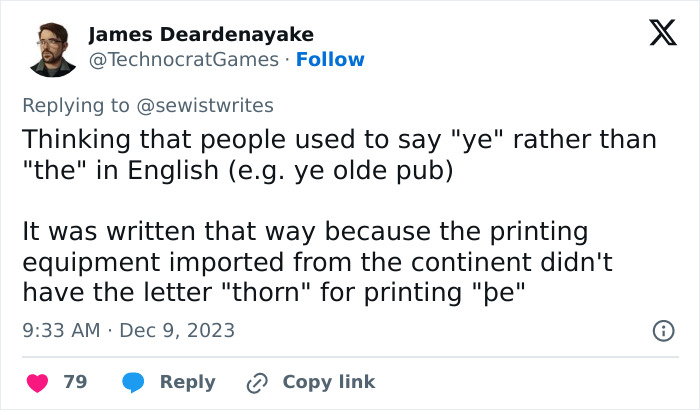

#15

Image credits: TechnocratGames

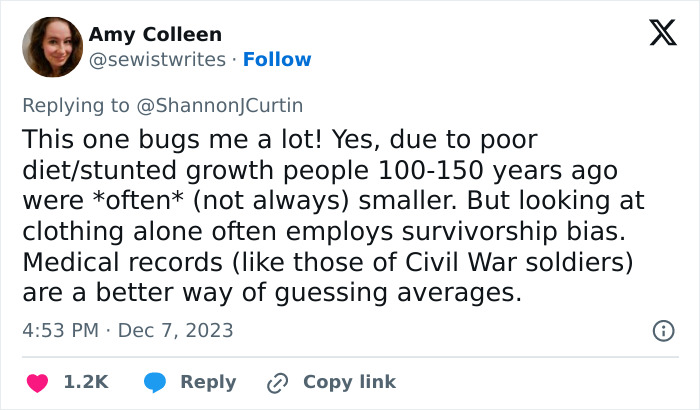

#16

Image credits: sewistwrites

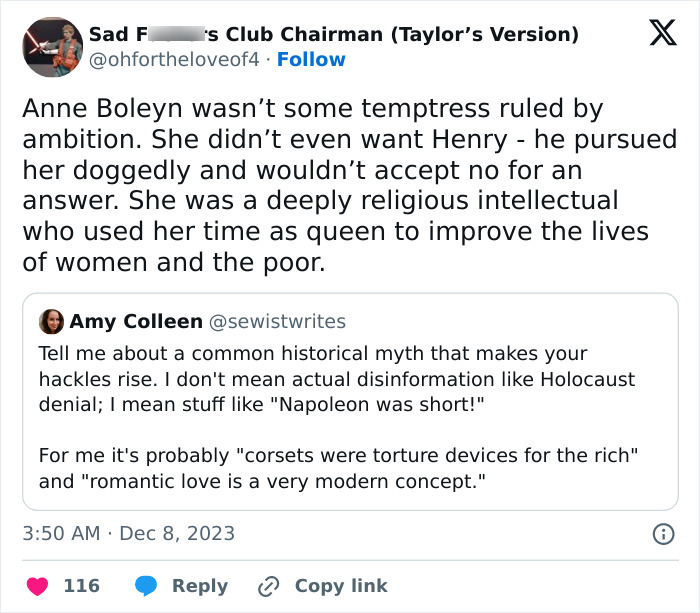

#17

Image credits: ohfortheloveof4

“I'm sure there are many factors in play, such as the unreliability of memory, differing eyewitness accounts, and the need to simplify complicated events into easy-to-follow narratives,” Assoc. Prof. Lunt told Bored Panda, discussing how false historical information becomes accepted as historical fact.

“But the one I think about the most is similar to how I approach myths—something about the non-factual version resonated with people, and that's why it stuck. In a way, it says more about the people who adopted and maintained that belief than it does about the historical (non-)event itself.”

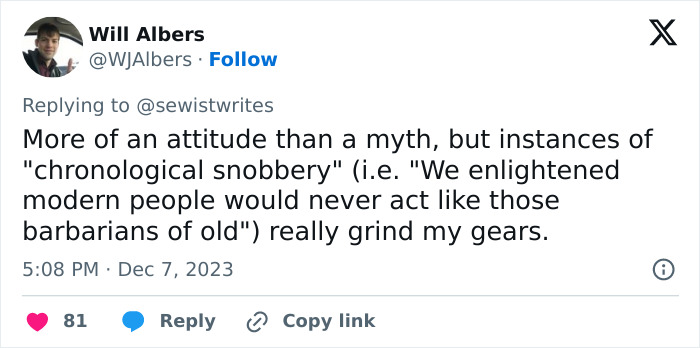

#18

Image credits: WJAlbers

#19

Image credits: DavidZsutty

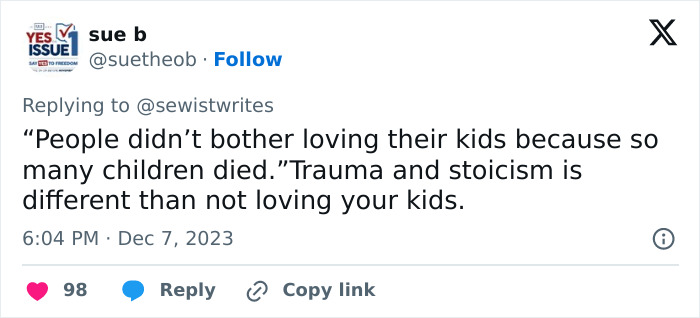

#20

Image credits: suetheob

Lunt expanded that the way historians approach myths is not whether they are “true” (as in factual) or not, but what they reveal about the people who told them and believed them. “So, with something like the Trojan War as told by Homer, it's clearly a myth but the values of its characters reveal the values of the ancient Greeks during the time it was composed,” he provided an example.

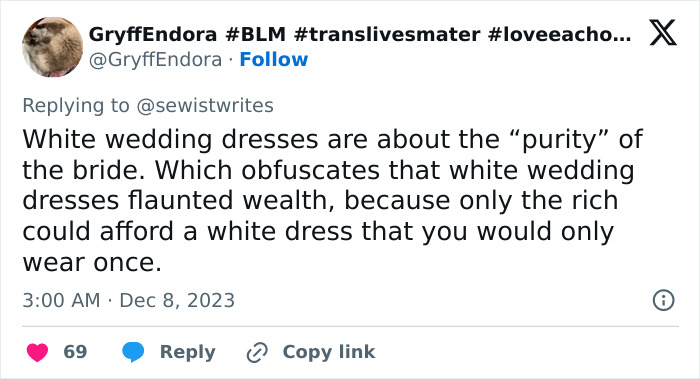

#21

Image credits: GryffEndora

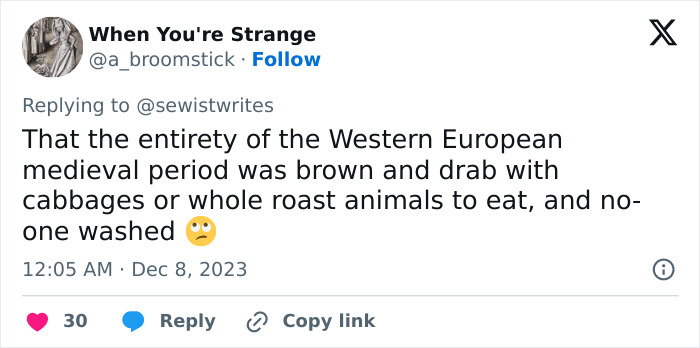

#22

Image credits: a_broomstick

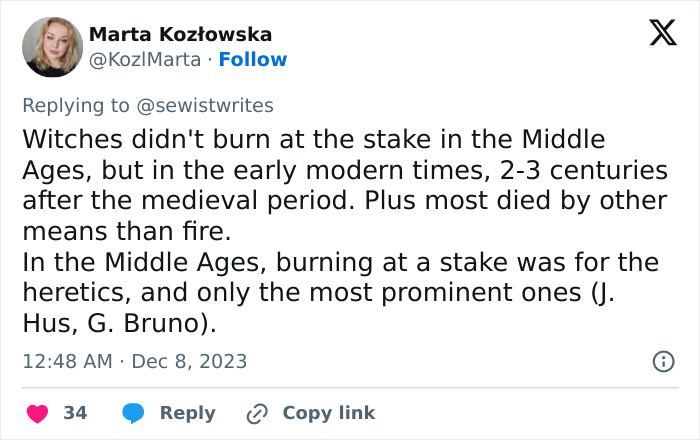

#23

Image credits: KozlMarta

Assoc. Prof. Lunt continued to share more examples of how myths work in the context of history. “One of the most prevalent myths about the Punic Wars between ancient Rome and ancient Carthage is that, after Rome conquered Carthage in the third war in 146 BCE, the Romans destroyed the North African city and sowed the land with salt, so that nothing would grow there. It's a powerful image that is repeated often enough, but really has no basis in the historical record.”

The expert pointed out that some authors suggest that the myth of sowing salt at Carthage possibly came from the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, where the city of Shechem is destroyed and sown with salt.

“Perhaps that is the case; perhaps not; but it's easy to see modern narratives attempting to juxtapose the inevitable triumph of the Israelites with the inevitable triumph of Rome over their enemies,” he said, adding that “inevitable” in this case means that people in the future who write the histories know how the past turned out.

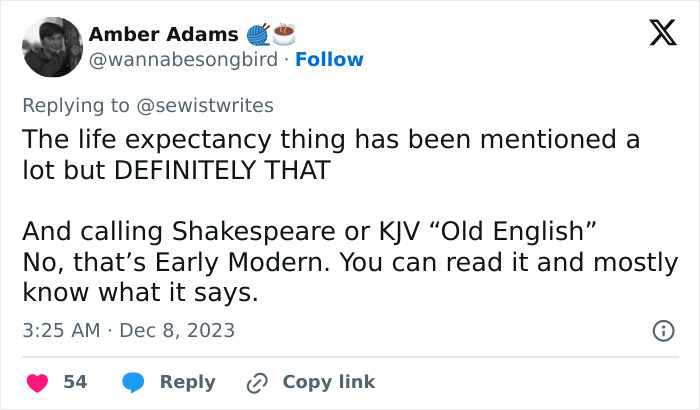

#24

Image credits: wannabesongbird

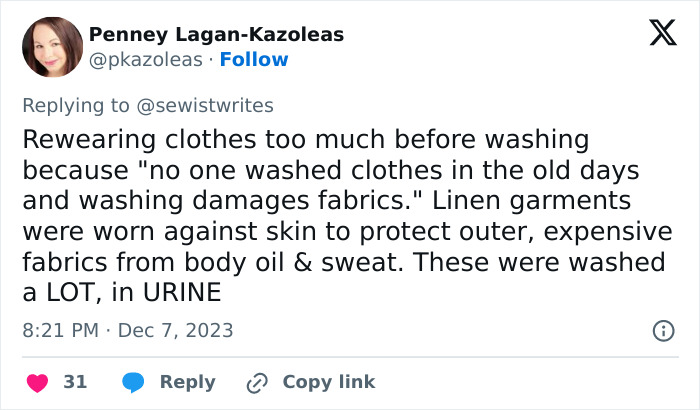

#25

Image credits: pkazoleas

#26

Image credits: LukaCopelli

Lunt discussed another example of a prominent—now faded—myth from ancient history, which is the belief that ancient athletics were for "amateurs".

“As modern sport developed in Britain and Europe, and as the Olympic Games were revived in their current form in the 1890s, 19th-century British sporting ideals of ‘amateurism’ were transferred onto ancient Greeks in order to justify the British class-based system of sport and education. The notion came from the fact that Greek athletes who triumphed at Olympia received only a crown of olive leaves (although they received lucrative prizes in other venues).

“This reimagination of the ancient Greeks allowed British schools and sporting groups to systematically exclude anyone who labored for money, reserving their sporting endeavors for aristocrats,” Lunt explained.

“It's more complicated than this, of course, but the gist of it is that the modern Olympics clung to its notion of amateurism for a long time—the 1990s is when most Olympic competitions became open to professional athletes; the Dream Team of NBA players in Barcelona in 1992 was a watershed moment.”

The expert added that even now, in the US, we are watching the last vestiges of amateurism wash away on college campuses as various deals allow players to make money from their athletic endeavors.

“In the end, this says more about the people of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries than it does about the ancient Greeks. The intensely classist system of 19th-century Britain invented an ancient practice to justify its own exclusion of lower-class athletes. This transferred to the United States on college campuses, long a bastion of upper-class privilege in the USA. It wasn't until the 1980s that David Young published The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics that the belief in ancient amateurism was torn down,” Lunt said.

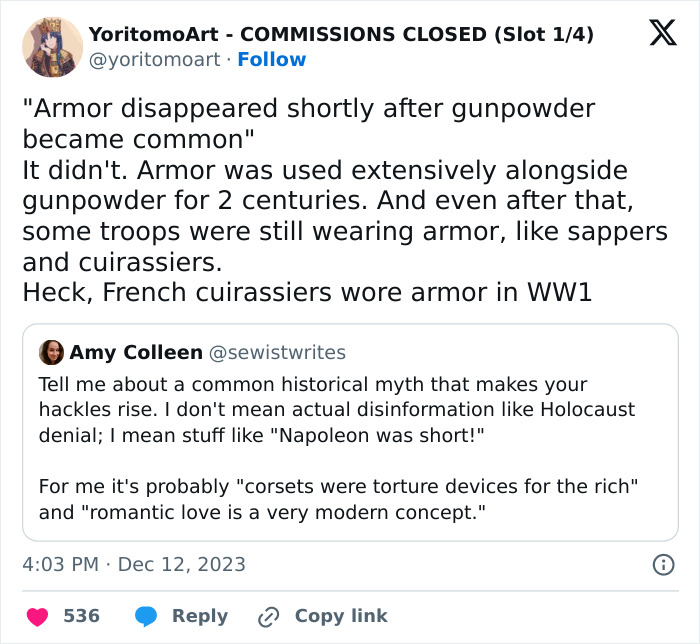

#27

Image credits: yoritomoart

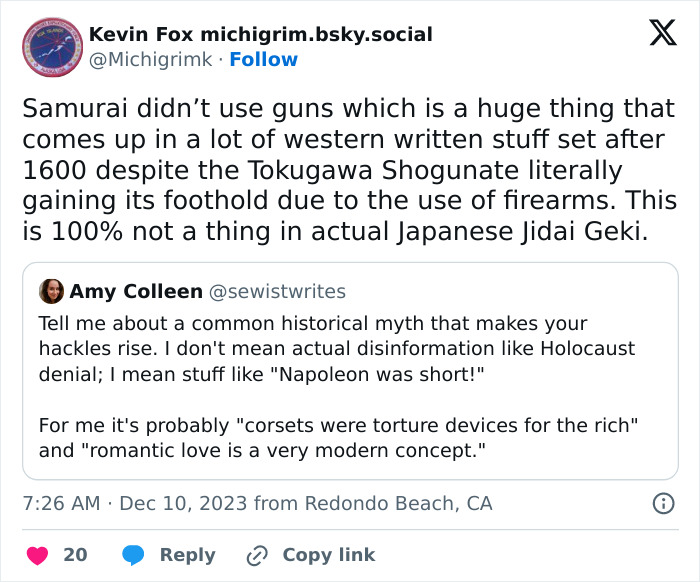

#28

Image credits: Michigrimk

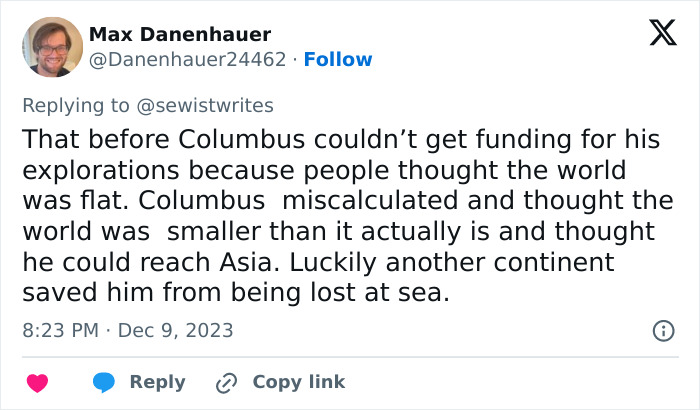

#29

Image credits: Danenhauer24462

“I think we all today are well versed in notions of ‘fake news’ or ‘revisionist history’, or whatever skeptical approach we wish to employ when trying to comprehend and understand the events of the past,” Lunt said, discussing how myths around certain historical events affect the way people view the past.

“On the super-cynical side, some people would state that the past is ‘unknowable’ and we each have our ‘own truth’ as we saw it and see it. On the super-literal side, those who need their preferred version of history to be true, no matter what the evidence indicates, are just as guilty of being unwilling to engage with other viewpoints.

“Ultimately, in my opinion, both of these approaches reveal as much, maybe even more, about the people who wrote the history, or the people today who accept or reject it, than the recorded events themselves.”

#30

Image credits: melissabreenx