Rivalries can bring out the best in us. Whether we’re talking comic book heroes, sports franchises, or personal grudges, not-so-friendly competition can inspire all sorts of feats and innovation. During the ‘90s, Sega and Nintendo were locked in an epic console battle for living room supremacy. So it’s only natural that when Nintendo launched the Game Boy and created a market for on-the-go gaming the team at Sega needed to respond.

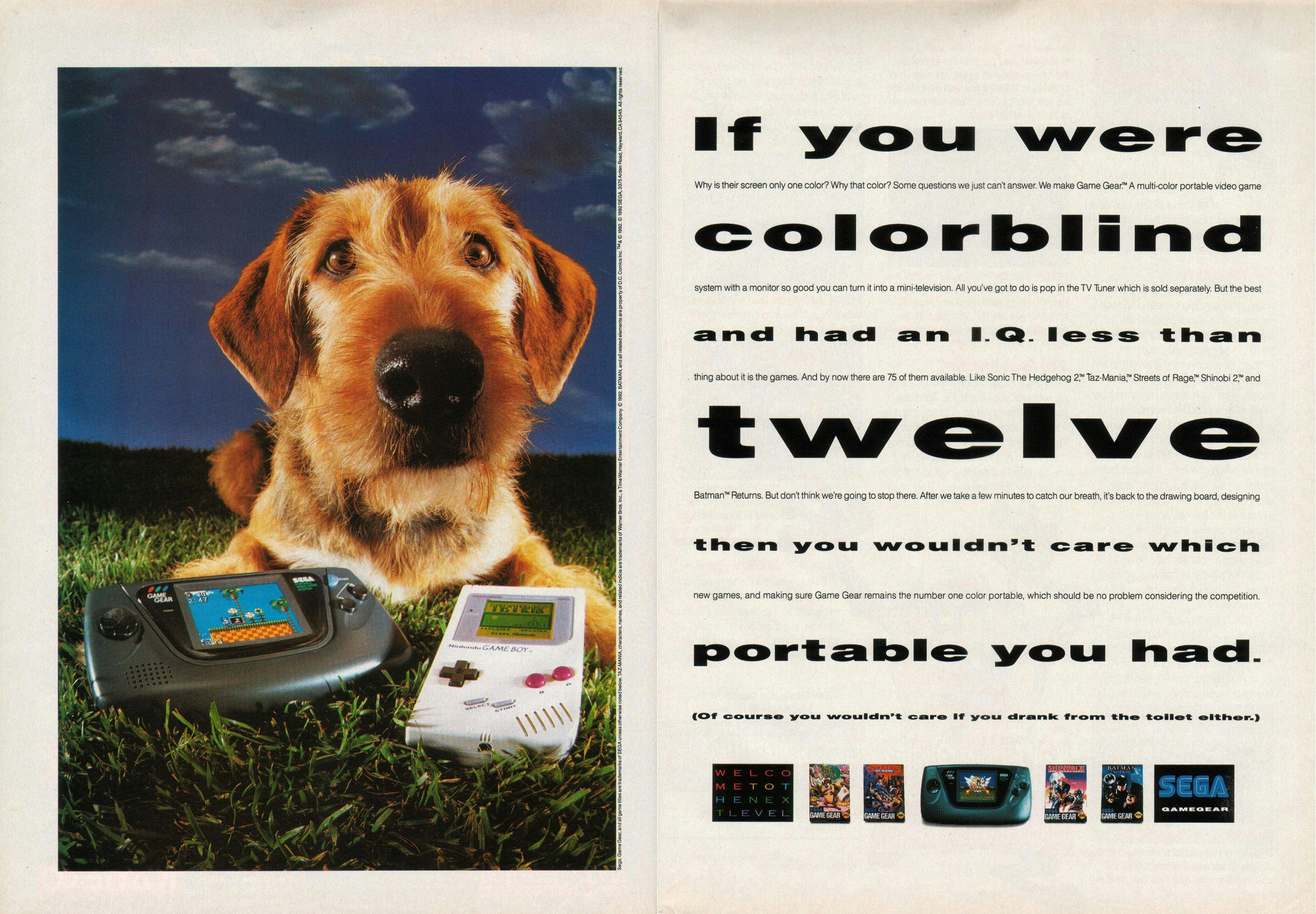

When Sega unveiled the Game Gear on October 6, 1990, it was a deliberate, teeth-baring challenge to Nintendo’s Game Boy. Sega sold a story that ran a stark contrast against the Game Boy’s dull grey and green aesthetic. The Game Gear felt like a pocket-sized slice of the Genesis era. It had a backlit color screen, better ergonomics, and hardware that promised a clear technical edge. So what went wrong?

Commercially the Game Gear was a modest success for Sega, but it never threatened Nintendo’s dominance. Sega reported shipping roughly 10 million units. Those figures beat contemporaries like the Atari Lynx and TurboExpress, but were dwarfed by the Game Boy’s eventual 100+ million install base.

Critically, responses were mixed but forgiving. Reviewers praised the Game Gear’s color screen, solid resolution and its ability to reproduce arcade-style experiences in handheld form. Common criticisms zeroed in on two recurring problems: terrible battery life (roughly 3–5 hours on six AA batteries under normal conditions) and a sometimes washed-out screen that struggled in direct sunlight. The Game Gear’s sales and lifespan reflect both technical ambition and strategic limits. It won hearts and dominated headlines, but lost on the platform numbers that decide whether ecosystems can stick around.

On paper, the Game Gear was a better system thanks to its color screen and enhanced graphics. But in practice, it just didn’t have the developer support it needed to go the distance. Exact numbers are fuzzy, but estimates put the Game Gear library at around 250 titles. This is roughly half of what was available on the Game Boy. And, excellent Sonic the Hedgehog games notwithstanding, much of the catalogue leaned on ports rather than the deep first-party investing that made Nintendo’s handhelds indispensable. It seemed like rather than games, the Game Gear’s focus was on gimmicks.

Accessories were both a selling point and a symptom of Sega’s “more is more” approach. Some of them were great. The Master Gear Converter allowed the Game Gear to play Master System cartridges, broadening the software pool. Car adapters and battery packs helped alleviate some of the endurance issues. Other accessories, like a TV antenna that never seemed to work, or a clunky magnifying lens contraption to make the screen seem bigger, turned the ergonomically superior Game Gear into a cumbersome monstrosity.

The Game Gear’s launch exemplified Sega’s larger ’90s persona: aggressive marketing, memorable ads that mocked the Game Boy, and a snarky Hedgehog mascot who was a hip contrast to a certain mustachioed plumber. Sega pushed hard in Western markets with this bold and edgy messaging, and it helped Sega punch above its weight even if the Game Gear ultimately lost the battle with Nintendo’s Game Boy.

Behind the scenes, Sega’s internal culture and fast-moving product cycles shaped the handheld’s story. The Game Gear was developed in an era when Sega’s reseaech and development groups were experimenting aggressively. Hideki Sato and other R&D veterans later reflected on that era with a mix of pride and hindsight, noting both creative risk and strategic missteps as Sega chased multiple hardware bets. The Game Gear served as the first of several failures that would ultimately define Sega’s legacy.

The Sega Genesis followed a similar Voltron-esque trajectory as the Game Gear courtesy of Sega CD and 32X add-ons. The failure of these peripherals is part of what caused Sega to rush the launch of the Sega Saturn in 1995, which struggled from a similar lack of third-party support in its launch year before it was wiped off the marketplace by the Nintendo 64. The Sega Dreamcast, like the Game Gear, contained notable hardware improvements but found itself outmatched by newcomer Sony’s DVD-supporting PlayStation 2.

The Game Gear lives as the most vivid “what if” of handheld history. It proved color handhelds were viable and influenced how later portable makers thought about screen technology and ergonomics. But its story also serves as a cautionary tale: technical specs and flashy features won headlines, but performance, price, and software win gamers.