In the 1990s, developer Square — which had yet to merge with rival Enix — was on a roll. Within just a few years, the studio released a handful of the most beloved Final Fantasy games, along with classics like Final Fantasy Tactics, and Chrono Trigger. It seemed that almost everything it produced in that period either defined the series it was part of or launched successful sequels of its own. A few years after the PlayStation’s launch, Sony saw the success of these turn-based RPGs and wanted a game of its own to rival Final Fantasy. It took a historically big swing on a brand-new RPG, only for it to flounder on launch and be all but forgotten a quarter of a century later.

The Legend of Dragoon was released in North America on June 13, 2000, six months after its debut in Japan. Set in a medieval fantasy world of humans and dragons, The Legend of Dragoon opens with the protagonist’s village being destroyed and his childhood friend kidnapped, kicking off a quest that eventually leads the party to confront an evil god. If that all sounds a bit too familiar to you, players at the time felt the same way.

“We started the project in 1996 with only a handful of people,” according to former Japan Studio producer Shuhei Yoshida.

At the time production began, Sony was also working on Ape Escape and Ico, and couldn’t spare additional staff. But by the time development was in full swing, that team had grown to 100 people, a massive size for a game at the time, including ten artists working just on concept art. The game’s budget itself was just as large, at a reported $16 million. While games can easily cost a studio like Sony many, many times that amount today, it was incredibly pricey by the standards of the late ‘90s. That all resulted in a game that was itself gigantic, spread across four discs (the most a PlayStation game case could hold) and stuffed with expensive cutscenes meant to show off the console’s power.

You can still see the parts of The Legend of Dragoon that were genuinely impressive if you boot it up today. The game’s opening cutscene, portraying the razing of a village, looks fantastic, standing up to any of Square’s own RPGs on the PlayStation. That’s quickly followed by a sequence of main character Dart being chased through a forest by a massive dragon, which, while certainly looking more dated than the opening cutscene, is still a solid sequence for its time.

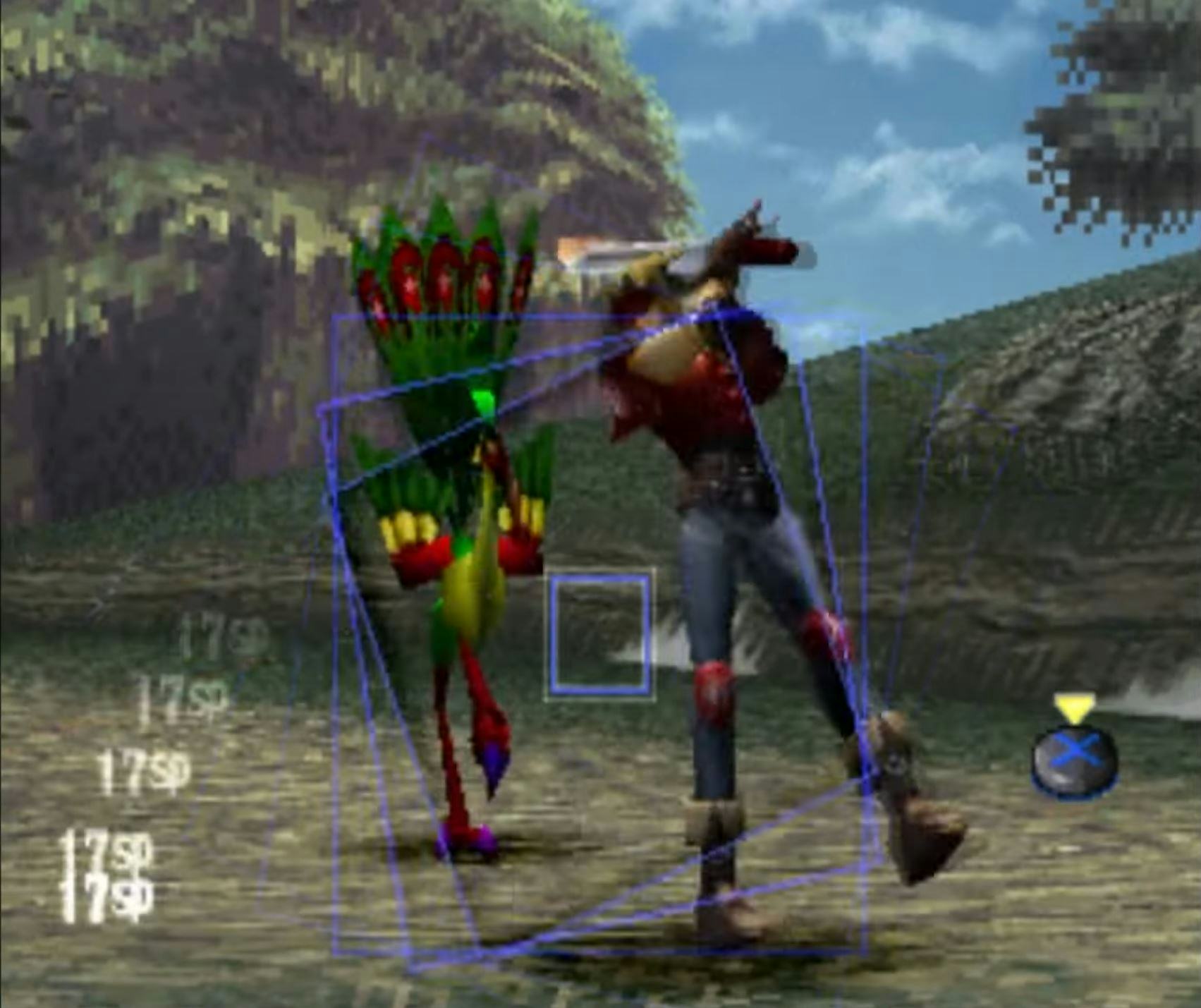

Once combat begins, The Legend of Dragoon starts to seem even better. The game’s director, Yasuyuki Hasebe, was previously a battle designer on Super Mario RPG at Square, and after making the jump to Sony, he brought one of that game’s most distinctive combat ideas with him. In battle, The Legend of Dragoon combines turn-based attacks with timed button presses, adding damage to your attacks if you match your inputs to patterns shown on screen. Known as additions, these empowered attacks each have their own patterns, making fights more interactive.

The problem is that, despite all the money Sony poured into the game and all the talent present on its development team, The Legend of Dragoon simply doesn’t hold up to its fantastic first impression. The stunning CGI used in its opening cut-scene gives way to a fine but in no way groundbreaking visual style in the rest of the game. The combat system that at first makes every battle so engaging eventually becomes more of a chore than a thrill. And while there have certainly been worse stories told in RPGs, The Legend of Dragoon’s plot is unremarkable in the end.

Yet none of this is to say that The Legend of Dragoon was never worth playing or that it was a mistake for Sony. The game got middling reviews at launch and has resisted the canonization of so many other RPGs of its era, but it sold well enough to keep Sony happy and still has plenty of fans. After its launch on PSN in 2012, The Legend of Dragoon is now easily accessible for anyone who’s interested in RPG history but doesn’t want to dig out decades-old hardware to investigate it. Rather than a failure, what The Legend of Dragoon is in the end is a reminder that no amount of money or big-name developers can guarantee a game’s success — and that there’s nothing wrong with enjoying one that’s just okay.