Germany's Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) has reported that the North Sea endured its warmest year ever in 2025, with average surface temperatures hitting 11.6°C – the highest since records began in 1969.

The announcement from Berlin underscores accelerating ocean warming driven by climate change, as confirmed by Tim Kruschke, head of the BSH's climate team.

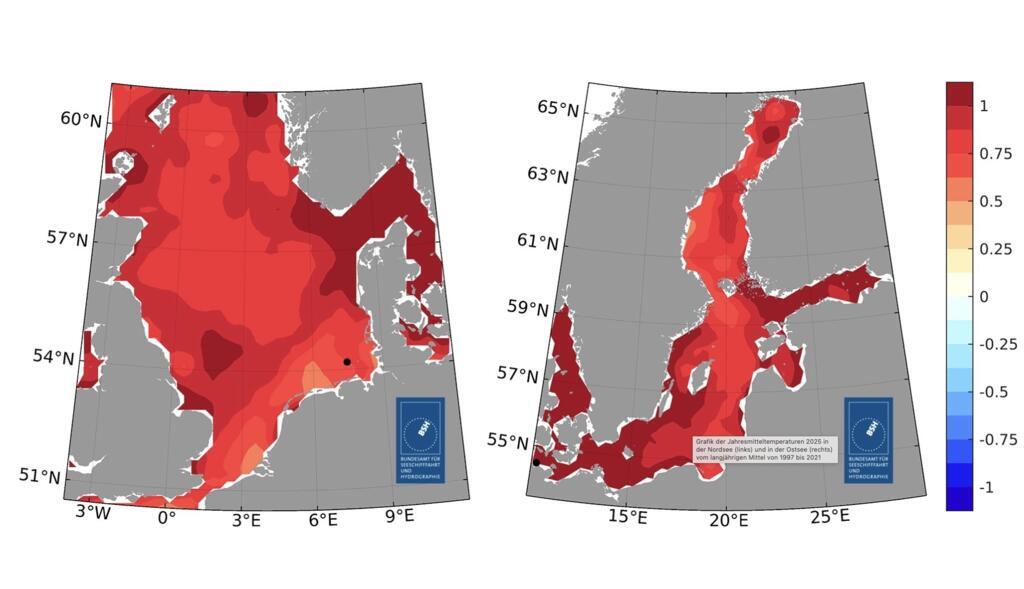

The Baltic Sea, meanwhile, came close to its own record, averaging 9.7°C last year – 1.1°C above the 1997-2021 long-term mean and second only to 2020 since monitoring started in 1990.

Throughout 2025, the North Sea shattered seasonal benchmarks. Spring saw averages of 8.7°C, 0.9°C above normal and the hottest since 1997, with peaks up to 2°C higher off Norway and Denmark.

Summer was even more extreme, reaching 15.7°C on average – edging out 2003 and 2014 for the top spot since 1969, with vast swathes exceeding long-term averages by over 2°C.

The BSH noted prolonged marine heatwaves, including a 55-day event at Kiel Lighthouse from late March to May – the longest on record there since 1989. These events stemmed from reduced cloud cover, enhanced solar heating, and inflows of warm Atlantic water.

Anomalies

Such anomalies align with global patterns outlined by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC.) Oceans have absorbed over 90 percent of excess atmospheric heat since 1970, with warming rates more than doubling since 1993 – from about 3-4 Zetajoules (ZJ) per year (0-2000m depth) pre-1993 to over 6 ZJ annually thereafter. One Zetajoule equals the energy from exploding 239 million Hiroshima bombs or powering the world for a year at current rates.

Marine heatwaves have doubled in frequency since 1982 and grown more intense worldwide. UNESCO's 2024 State of the Ocean report echoes this, noting ocean warming doubled over 20 years, fuelling deoxygenation (2 percent loss since 1960s), acidification (up 30 percent since pre-industrial times), and 40 percent of recent sea-level rise from thermal expansion.

UN Summit advances ocean protection, vows to defend seabed

Warmer seas also threaten North Sea biodiversity, a key European fishery. Heatwaves disrupt plankton, fish distributions, and oxygen levels, creating "dead zones" and stressing cold-adapted species. Zooplankton collapses during 2018-2022 events signal worse ahead, while species shifts could boost some sharks or oysters but risk invasives and ecosystem imbalance.

The Baltic, warming faster long-term (nearly 2°C since 1990), faces amplified risks like seabed hypoxia. Coastal communities brace for fiercer storms and erosion as seas expand and weather intensifies.

(WIth agencies)