When I picture the 1989 football season, I see mud. Footage of Melbourne games invariably shows players shin deep in the stuff. That winter, it seemed like it didn’t stop raining in Melbourne. The MCG was a quagmire. Some players got stuck and wrecked their knees. Others, Barry Dickins once wrote, “dived into it like seals and pirouetted out of it like parrots.”

But there was no mud on grand final day – just balloons, sand, blood, violence and some of the best, most freewheeling football ever played. Everyone remembers it differently. I remember John Farnham – who loved a big occasion – sprinting onto the MCG, his permanent tag Glen Wheatley hot on his hammer. I remember the hazy glare that enveloped the stadium in the second half. I remember the streaker dressed as Batgirl running on at a critical point in the game, a day after the Batman movie had opened in cinemas.

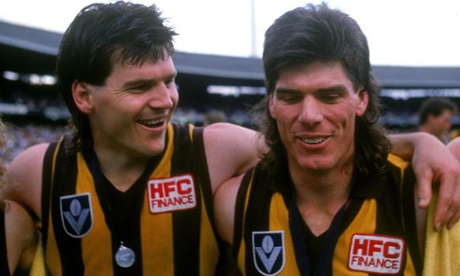

I remember Robert DiPierdomenico. In later years, he would ham up his cuddly, moustachioed, seven-syllabled persona. But he was a frightening proposition. On the Thursday before grand finals, he would tear around Glenferrie Oval like an escaped mental patient. ‘Born to Play Grand Finals!’ he would scream, over and over. ‘Born to Play Grand Finals!’

Gary Ablett Sr, running at full pelt and with murder in his eyes, nearly killed Dipper that day. His lungs shut down. He started (and I can scarcely believe I’m typing this) to inflate. He would end up on a hospital trolley. His lunging tackle in the dying seconds, with his life very much on the line, deserves a more prominent place in football folklore.

Like Dipper, Dermott Brereton was made for games like this. He too, presumably pondered his mortality that day. As the teams lined up for the national anthem, he stood like a man posing for his own statue. Ninety seconds later, he was lying flat on his back, his ribs broken and his kidney lacerated. “How does that feel?!” his assailant Mark Yeates screamed in his face. Brereton turned grey and vomited. “I’m coming good… I’m coming good,” he coughed. And he did. He marked over the much smaller Steven Hocking and goaled. Hawthorn were up and away and Brereton’s legacy was secure.

In many ways, the world of VFL football was too small for Brereton. Unlike Ablett, who may have found something verging on contentment as an anonymous country footballer, Brereton needed the big time. He needed a Super Bowl or a title fight at Madison Square Garden to do justice to his personality. When he speaks of that day, his pectorals puff out a little more than usual, as well they might. These days, about 25 % of what he says makes more sense than anyone else in the game. The other 75% can leave you scratching your head. Few have better expressed exactly what it feels like to run out in a grand final. “It actually makes contact with you,” he wrote in a column for The Age nearly two decades ago. “It surrounds you and slaps at your sides. If you could imagine standing in an empty swimming pool and then all of a sudden, the full volume of water is poured in from every direction simultaneously. Some players are unnerved by it. Some love it.”

Geelong’s young players, at least initially, were unhinged by it. While the Hawks kept their heads, the Cats’ eyes were rolling in the back of theirs. And they were leaking goals. “Offence sells tickets but defence wins championships,” the old saying goes and Geelong didn’t really do defence at all. Indeed, it’s hard to think of a more defensively inept outfit than the Geelong teams of that era. ‘You kick 22 – we’ll kick 25!” was the mantra at Kardinia Park. It made for great theatre. But it didn’t deliver premierships. Bruce Lindner’s grand final encapsulated the mindset. He was typically creative and won plenty of the ball off halfback. Yet the sight of his direct opponent – whether Dean Anderson, Gary Buckenara or Chris Whitman – slaloming into open goals was one of the recurring images of the game. He must have had eight goals kicked on him all up.

Geelong personified the era of part-time footy hero. Andrew Bews was a plumber who was digging trenches after the grand final parade. Mark Bairstow was training thoroughbreds. Ablett had a string of perfunctory jobs and inglorious exits. Steven Hocking was a bricklayer. Paul Couch and Garry Hocking were garbos who would run upwards of 10km on concrete the Friday before a game. On the Sunday following the preliminary final, key forwards Billy Brownless and Barry Stoneham arrived home at daylight on the back of a garbage truck. Before the game, coach Malcolm Blight was chain smoking in the rooms. They were, for the most part, Geelong locals and country lads from the rural townships of northern Victorian.

Compared to the Cats, Hawthorn seemed positively preppy.

Growing up football mad in Melbourne, coaches and teachers would sometimes bus us off to Glenferrie Oval to watch the champs train. Hawthorn’s recruiting zones included the Mornington Peninsula and Western Gippsland. But they were always seen as a private school team, with a few Italian and Irish renegades thrown into the mix. Brereton, at the apex of his fame, would swagger onto the training track like Viv Richards walking out to bat at Antigua. It was an era where coaches flogged their players – three-hour punishment sessions in mid-winter, 100x100m sprints and the like. Allan Jeans’s Hawthorn did nothing of the sort. They trained at a blazing intensity for about 45 minutes in what mainly seemed to constitute high-end circle work. Flawless skill execution at full speed was the focus. Jeans, his socks tucked into his tracksuit pants, would throw his voice across postcodes. “RUN LADDY!” he would bellow. “RUN!”

Their rooms at half-time must have been something to behold. Brereton was urinating blood. Dipper’s lung was leaking. John Platten was speaking sideways. Gary Ayres was hobbled. Michael Tuck, at the ripe old age of 122, seemed to have aged another century. Everyone’s face was beetroot red, courtesy of the heat, the violence and the breakneck speed of the game.

Sensing the gravity, Jeans is said to have given one of the great sporting rev-ups. At funerals, at reunions and on panel shows, they still refer to it. As they ran out for the second half, Brereton’s best mate, Chris Wittman, stood in front of him, put his hand on his shoulder and with tears in his eyes, said: “I love you mate.” The Old Xaverian bromancing the Frankston hood - it was that sort of day. Hawthorn were six goals the better. But they were running out of players. And Geelong had a creature from another planet prowling the forward line.

Watching Ablett, week-in, week-out, the overwhelming impression was of a man who didn’t know what was going on, who didn’t know how good he was. Sometimes, when he had that foggy, vacant look in his eye, he would still turn it on. Other times, he may as well have been back home trapping rabbits. On this day, from the moment he stood for the national anthem to when he collected the Norm Smith Medal and thanked his saviour – he was fully present. Indeed, as he mounted the dais, he kept nodding. “Yep, yep,” he seemed to be saying to himself. “I was pretty bloody handy today.”

On the Monday after the final, there was a cartoon in one of the newspapers depicting a crestfallen Ablett walking across Port Phillip Bay, his bag slung over those slopey shoulders. “A disappointed Gary Ablett heads home after the grand final,” the caption read. Cartoons and still pictures in many ways did Ablett more justice than watching him live or on TV. They captured his strange angles, his blank eyes, the curious mix of sadness and joy that he elicited. The 1989 grand final was a very Ablett masterpiece however. Nine of the best goals we’ve ever seen. But no win. And his second opponent Chris Langford ran off him repeatedly to drive the Hawks into attack.

The game is very different now. Players are ‘stakeholders’. Footballers are icing their ankles at 5am these days, not clinging onto the back of garbage trucks. Toughness in 2014 is apparently cultivated by letting oxygen-masked intruders into your house at 3am, subjecting your 13 year-old son to a regime that would have Ivan Drago reaching for an aspirin.

It was the last and possibly the best of the VFL grand finals. But footy didn’t necessarily change that day. The sport took a decidedly different trajectory a couple of years later with the emergence of the West Coast Eagles. They were total professionals – unknowable, muscled-up assassins from across the Nullarbor. They eschewed all-out attack, played through quarterbacks and chipped the ball down the line.

Still, Australian rules football may have reached its zenith on that sunny September Saturday. Never again would it be so bold, so brutal, so dangerous, so uncomplicated. Never again would it be so much fun. It’s been a quarter of a century. It feels like yesterday.