Although the early 21st century saw many non-English language films becoming popular in American markets, Hollywood was still unwilling to let imaginative works of genre fiction exist within their own context. The Grudge, Martyrs, Mirrors, Pulse, and One Missed Call are just a fraction of the excellent international horror films that inspired disastrous remakes that failed to understand the cultural context of their originals. Bad remakes like Friday the 13th or A Nightmare on Elm Street can exist without ruining the legacy of their predecessors, but a misjudged reinterpretation of a foreign arthouse title can do permanent damage to the original film’s standing.

Let The Right One In was instantly heralded as a Swedish classic, as Tomas Alfredson's intimate adaptation of John Ajvide Lindqvist’s novel offered a unique perspective on vampire mythology. Rather than heightening the gore, Alfredson chose to tell an emotional story about two children forced to become outsiders due to societal constraints; that one of them was a vampire over 200-years-old made their connection even more fraught.

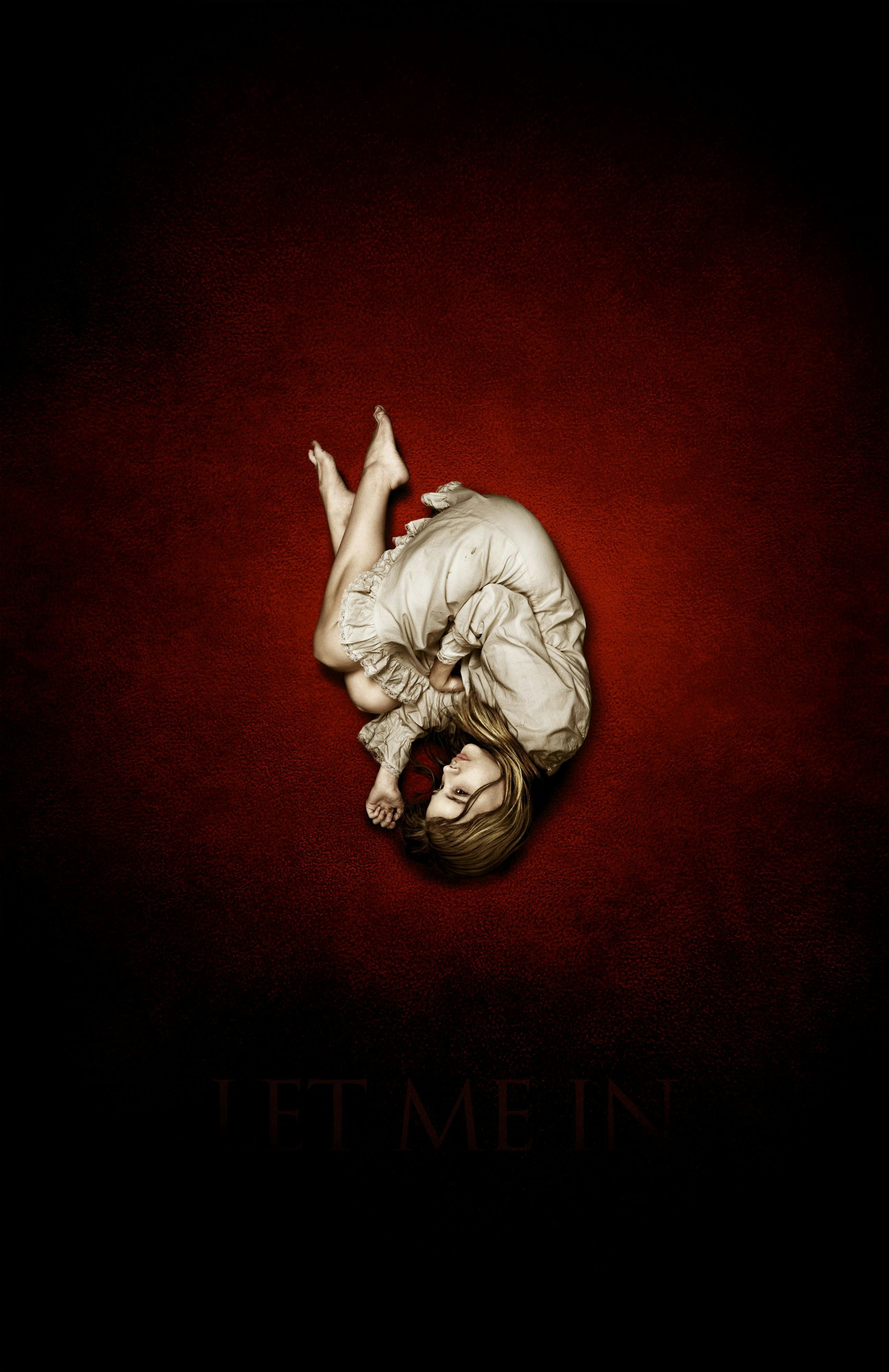

It was the same year that Let The Right One premiered that Hammer Films acquired the rights to produce an English-language remake, and even offered Alfredson the opportunity to direct it. His refusal wasn’t the first sign that the project may have been ill-conceived; Let The Right One used the poverty and social divisions in Stockholm to explore the darkness of both characters, which would be lost if the story was transposed to an American setting. However, Matt Reeves was offered the chance to helm the project shortly after his found-footage film Cloverfield became a surprise hit. Reeves’ film, Let Me In, wasn’t a derivative replication of Let The Right One In, but proof that the story was accessible enough to be interpreted in a different setting.

Although the central relationship of Let Me In is similar to its predecessor, Reeves filled in gaps regarding both characters’ upbringings. The meek 12-year-old boy Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) spends many nights in the lonely space by his apartment complex, as his bickering parents’ divorce has made his home inhospitable. He shares a friendly encounter with his new neighbor, Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz), who has moved in with her caretaker Thomas (Richard Jenkins). Although Owen initially assumes the mysterious older man is her father, he learns that Thomas was 12-years-old himself when he first met Abby, a vampire he has spent decades providing for by delivering victims.

Let The Right One In was unrelentingly suspenseful in how it showed a young boy grappling with a dangerous secret, but Let Me In dared to question the humanity of each character. Rather than the sinister executioner that appeared in Let The Right One In, Jenkins gives a heartbreaking performance as Thomas, a man who was once in the same position as Owen. Although he has accepted that guardianship of Abby means doing some nasty things, a scene where he refuses to murder a young man suggests that he has limits. Thomas provides a contrast to Owen’s mother (Cara Buono), whose appearance is limited to a series of argumentative shouts that her son is forced to endure. By denying the warmth of a maternal relationship, Reeves allowed his audience to feel Owen’s isolation and fear.

Although both Let The Right One In and Let Me In are set in the 1980s, Reeves is more pointed in his political commentary, with experts from Ronald Reagan’s infamous “Evil Empire” speech heard on the radio during an opening montage. The ugliness of Reagan-era conservatism is also shown within the cruel bullying that Owen faces at school, as his “otherness” makes him an easy target. Bullying was a theme in the original film, but Let Me In provided a more cathartic moment when Abby teaches and encourages Owen to protect himself.

The anxiety of the Cold War is explored through Owen and Abbys’ communication, as they initially interact through the type of Morse Code messages that spies used to avoid detection. Many horror films have invoked skepticism as to how a supernatural incident could be ignored for so long, but Let Me In makes it clear that no one is monitoring the safety of those living in poverty. The most subtle addition Reeves made was to use Elias Koteas, who appears as an inquisitive detective looking into the recent murders, to also voice Owen’s unseen father. The implication is that to a scared child, all voices of intimidating authority sound the same.

Both Let Me In and Let The Right One In skirt around the queer themes of the original novel, which made it explicitly clear that Abby is an androgynous boy castrated centuries prior. However, the timidness shown by both Owen and Abby regarding romantic flirtations shows how Reeves effectively exposes the plasticity of the “nuclear family” unit lionized by the Reagan administration. His creative interpretation earned the praise of Lindqvist, who called it a “great American film” that “puts the emotional pressure in different places and stands firmly on its own legs.”

Reeves has been one of the few filmmakers willing to tackle existing properties by poignantly investigating their ideas — with Dawn of thePlanet of the Apes and The Batman, Reeves was able to challenge preconceived notions about franchises that had spanned decades. Remakes are often shallow, but Let Me In exists not as a cash grab, but as a fascinating companion piece to Let The Right One In.