There’s a fitting circularity to the fact that the new Bruce Springsteen biopic, Deliver Me From Nowhere, focuses on the creation of his 1982 record Nebraska. After all, the album begins with a scene straight out of a movie. “I saw her standing on her front lawn / Just a-twirling her baton,” sings Springsteen in the foreboding opening lines of the title track. “Me and her went for a ride, sir / And 10 innocent people died.”

The New Jersey rock icon wrote those words after seeing Terrence Malick’s 1973 neo-noir Badlands, which features a scene where Martin Sheen’s troubled greaser first encounters Sissy Spacek’s character twirling a baton on her front lawn. The film was loosely based on a real-life 1958 murder spree in Nebraska and Wyoming carried out by 19-year-old Charles Starkweather, who went on the run with his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate.

Springsteen’s subsequent fascination with the Starkweather case is dramatized in Deliver Me From Nowhere, starring The Bear actor Jeremy Allen White as the Boss in his early thirties. In one scene, White portrays the musician reading an old newspaper clipping describing the killings and scrawling in black marker: “Why???”

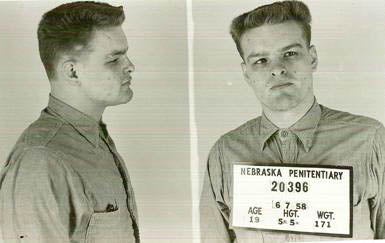

The Charles Starkweather killing spree

The question of how and why Starkweather became a murderer has concerned criminologists and psychologists for generations. He was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, the fourth of seven children in a working-class family. His father was a carpenter who often found himself unemployed due to a variety of ailments, including rheumatoid arthritis in his hands. He admitted at his son’s trial that he had been abusive to the boy, and was later divorced by his wife on the grounds of extreme cruelty.

When Starkweather was 17, he met Caril Ann Fugate, who was then just 13. He decided he wanted to marry her, but feared his life would be as hard and unfulfilling as his father’s. He dropped out of school, where he claimed he had been bullied over his bowed legs, speech impediment, and his family’s financial standing, and decided to turn to a life of crime. In December 1957, not long after he turned 19, he committed his first murder when he robbed a gas station and killed the attendant.

The following January, Starkweather went to Fugate’s home, but her mother and stepfather forbade him from seeing their daughter and told him to stay away. Starkweather shot and killed them before strangling and clubbing to death Fugate’s two-year-old half-sister, Betty Jean. He hid the bodies in an outhouse and posted a note on the front door saying the family had influenza, and visitors should stay away.

By the time police entered the house three days later, Starkweather and Fugate were on the road. They first went to a rural farm owned by August Meyer, a friend of the Starkweather family, in Bennet, Nebraska. Starkweather killed Meyer with a shotgun blast and killed his dog, too. The young couple hid out for a few days before setting off on foot. They were picked up by a pair of teenagers, Robert Jensen and Carol King, who Starkweather would ultimately kill as well.

He and Fugate drove Jensen’s car back to a wealthy area of Lincoln, where he broke into the home of industrialist Chester Lauer Ward. There, he killed Ward, Ward’s wife Clara and their maid Lilyan Fencl before setting off on the run again. Seeking an alternative car in Douglas, Wyoming, they shot and killed traveling salesman Merle Collison.

Sheriffs from Natrona County, Wyoming, finally caught up to Starkweather and Fugate when they were unable to operate the parking brake on Collison’s car. They were arrested and taken into custody on January 29, 1958, having killed 10 people in just eight days.

During his trial, Starkweather refused to answer when he was asked whether he felt any remorse for the string of brutal murders. In a letter to his parents, he wrote: “But dad I’m not real sorry for what I did cause for the first time me and Caril have [sic] more fun.” He initially said he had kidnapped Fugate, but later testified that she had willingly participated in their crimes.

Ultimately, they were both found guilty, and Starkweather was executed by electric chair in June 1959. Fugate received a life sentence and was paroled in 1976, having served over 17 years. In 2020, Nebraska authorities refused to pardon her for her crimes.

‘Nebraska’ is inspired by Starkweather’s perspective

In Springsteen’s bleak, sparse murder ballad “Nebraska,” sung from Starkweather’s perspective, he reworks the killer’s words as he declares: “I can't say that I'm sorry / For the things that we done / At least for a little while, sir / Me and her, we had us some fun.” The songwriter offers no neat explanation for their crimes, concluding with the words: “They want to know why I did what I did / Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.”

Along with the real-life crimes, while recording Nebraska, Springsteen was deeply influenced by the Southern Gothic tales of Flannery O’Connor. Those final lines seem to echo a character from her 1953 short story “A Good Man Is Hard To Find,” in which she wrote about a family who are slaughtered by a convict who calls himself The Misfit.

The Misfit claims that there is “No pleasure but meanness” in life, and that if Jesus can’t save him, then “there’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can — by killing somebody, or burning down his house of doing some other meanness to him.”

.jpeg)

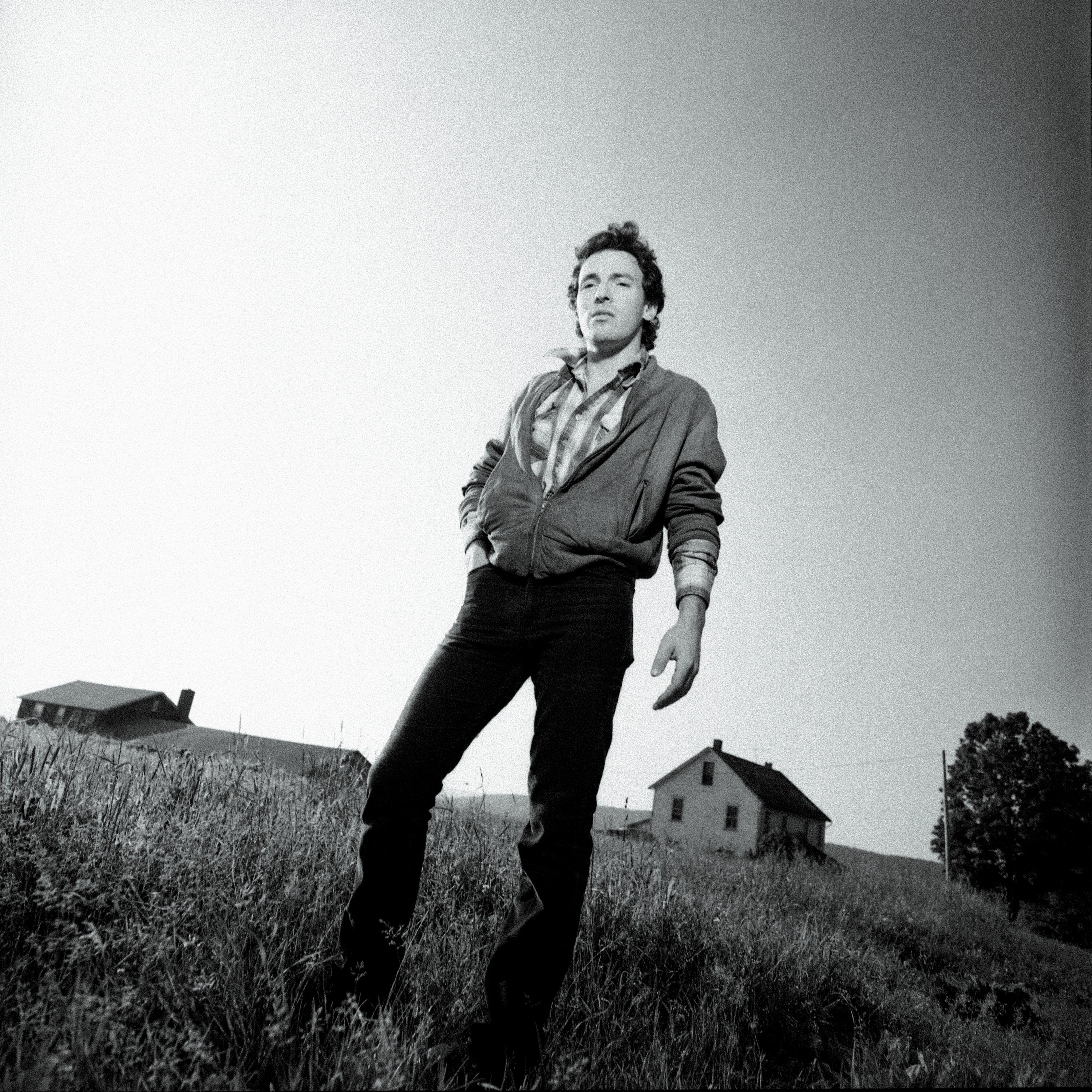

When Springsteen made Nebraska, he was at a turning point in his career. He had just released his most commercially successful album up to that point, 1980’s chart-topping The River, which produced hit singles like “Hungry Heart.” Many of the people around him had expected him to try and capitalize on that success by releasing another album that, like The River, would capture the exhilarating rush of the E Street Band’s live sound.

Instead, he found himself battling depression and searching for a new direction. As Springsteen told Warren Zanes for the 2023 book Deliver Me From Nowhere, which has been adapted for the new biopic, he was dealing with “conflicted feelings about being so separate from the people that I'd grown up around and that I wrote about.”

In the bedroom of his home in Colts Neck, New Jersey, he switched on a portable 4-track recorder and set about writing and recording a series of songs about down-and-out characters living outside the law. Influences like Badlands and O’Connor’s stories permeate music performed with just harmonica, guitar and Springsteen’s own ragged voice.

These songs… were restrained, still on the surface, with a world of moral ambiguity and unease below.

Although he rerecorded Nebraska with a full band at the Power Station studio in New York, Springsteen eventually opted to simply release his original home demos. Unexpectedly, the raw, chilling album became a chart hit, despite Springsteen’s decision not to tour or promote it. The Electric Power Station sessions are set to finally be released this month as part of a comprehensive Nebraska ’82 box set, and they offer a fascinating contrast to the original recordings that still display their inimitable, unrepeatable magic.

In the liner notes to the new reissue, Springsteen says he made that initial tape without any thought of releasing it, but that he now considers the album his finest work. “I was pretty much singing to myself,” he says. “I didn’t think many other people were ever going to hear it. The work was experimental, and that was all fine by me.”

The simplicity of the recording would go on to prove hugely influential, inspiring generations of lo-fi, DIY home recordings to come. In Zanes’s book, Matt Berninger of The National calls the album “the big bang of indie rock that was about making s*** alone in your bedroom.”

In his 2016 memoir Born To Run, Springsteen explained that, as well as Badlands and O’Connor, he was musically inspired by gospel, early Appalachian music and the blues. “I wanted the listener to hear my characters think, to feel their thoughts, their choices….” he wrote. “These songs… were restrained, still on the surface, with a world of moral ambiguity and unease below."

The creation of a dark, introspective album born from a period of internal conflict and uncertainty might not seem like rich material for a conventional music biopic, but that’s what makes Deliver Me From Nowhere an intriguing prospect. Like Nebraska itself, it’s not about the glitz and pomp of Springsteen’s glory days but the sort of quieter, more personal story that can sometimes be overlooked.

“I’ve written a lot of other narrative records,” Springsteen says in the liner notes for Nebraska ‘82. “But there's just something about that batch of songs on Nebraska that holds some sort of magic.”

Bruce Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere is in cinemas from October 24. The Nebraska ‘82 Expanded Edition box set will be released the same day.

The rote Bruce Springsteen biopic doesn’t do justice to its inspiration – review

Jennifer Lawrence recalls ‘humiliating’ nude dance scene with Robert Pattinson

Jeremy Allen White: The pressure of playing Bruce Springsteen was paralysing

Lily Allen’s West End Girl is a perfect exercise in unsparing honesty

Polly Samson on her photos of David Gilmour: ‘There’s an emotional intensity’

The story behind Bob Dylan’s protest song, ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’