Wearing sunglasses and a scarf obscuring his face, the armed ICE agent gets out of the SUV, approaches the vehicle and tells the activists that if they keep tailing him, they will be arrested.

“This is going to be your very last warning,” he says, as a fellow agent, his face also covered, begins filming us on his phone.

“You are impeding our operation,” he continues, adding as an apparent afterthought, “and traffic.”

Unperturbed, Will Stancil, 40, a local civil rights lawyer, responds calmly: “I have a constitutional right to follow you. I am not impeding the traffic.”

Stancil is among a growing network of “ICE commuters”, a large volunteer network of ordinary citizens in Minneapolis. They have given up weeks of their lives to patrol the streets and monitor the behaviour of federal law enforcement, as a crackdown grows increasingly deadly.

In the background in his car, the voices of volunteers chatter away on a “rapid response line,” a joint secure phone call that acts like a communal radio. They pool information about the whereabouts and actions of the 3,000 or so ICE agents and Border Guards currently deployed to the Midwestern city.

It is dangerous work.

Just last weekend, ICU nurse Alex Pretti, 37, was fatally shot in the street by two Border Patrol agents after intervening to help two women, according to a preliminary review of the incident.

His death, which has rocked the country, followed the fatal shooting of Renee Good, 37, a poet and a mother of three, by an ICE agent earlier in the month. City leaders have said she too was acting as a legal observer. (Citizens have a First Amendment right to film law enforcement doing their job as long as they don’t interfere).

The shootings, filmed from multiple angles, have sparked nationwide protests and outrage. Fuel was only poured on the fire when administration officials initially tried to label both of them “domestic terrorists.”

It has not dissuaded the volunteers from continuing the work of documenting the behavior of ICE agents, and their arrests — or “abductions” as volunteers prefer to call them.

This is essential so that we can alert the families of those taken, to ensure they do not simply disappear, explains another “ICE commuter” on a different patrol. She asks only to be identified by the code name “Blue Flame.”

“That is why, within the last six months, we have set up a homegrown 911-style emergency response system,” she continues.

Thousands are now involved in this decentralized network. Most know each other only by made-up call signs, fearful of infiltration and retribution from federal authorities.

“We also want to frustrate ICE’s efforts and demoralize them,” Blue Flame adds, explaining that it has been successful, with large-scale raids becoming less frequent.

She parks her car by the entrance to a mobile home park in a northeastern part of the city that has been raided multiple times in recent months, but not in recent weeks.

This is a “stationary” patrol, she explains, where volunteers guard an area, acting as both observers and a deterrent to any ICE activity.

“It is staggering to experience the actual fascism that I had only read about in history books,” she says, breaking down into tears. “We are living in an authoritarian regime.”

Over the last month, the world has been rocked by disturbing images of ICE agents violently seizing individuals they accuse of being in the country illegally, including children as young as five, as well as US citizens.

The level of violence has reached a point where even Republicans and, in a bizarre twist, the National Rifle Association, have criticized what is happening. The NRA was angered by the Trump administration, apparently blaming Pretti’s killing on the fact that he was legally carrying a gun.

Trump, who is worried about expected losses in the upcoming November midterms, initially softened his rhetoric. In an apparent bid to ease tensions, he sent home Gregory Bovino, the Border Patrol commander and public face of his mass deportation drive.

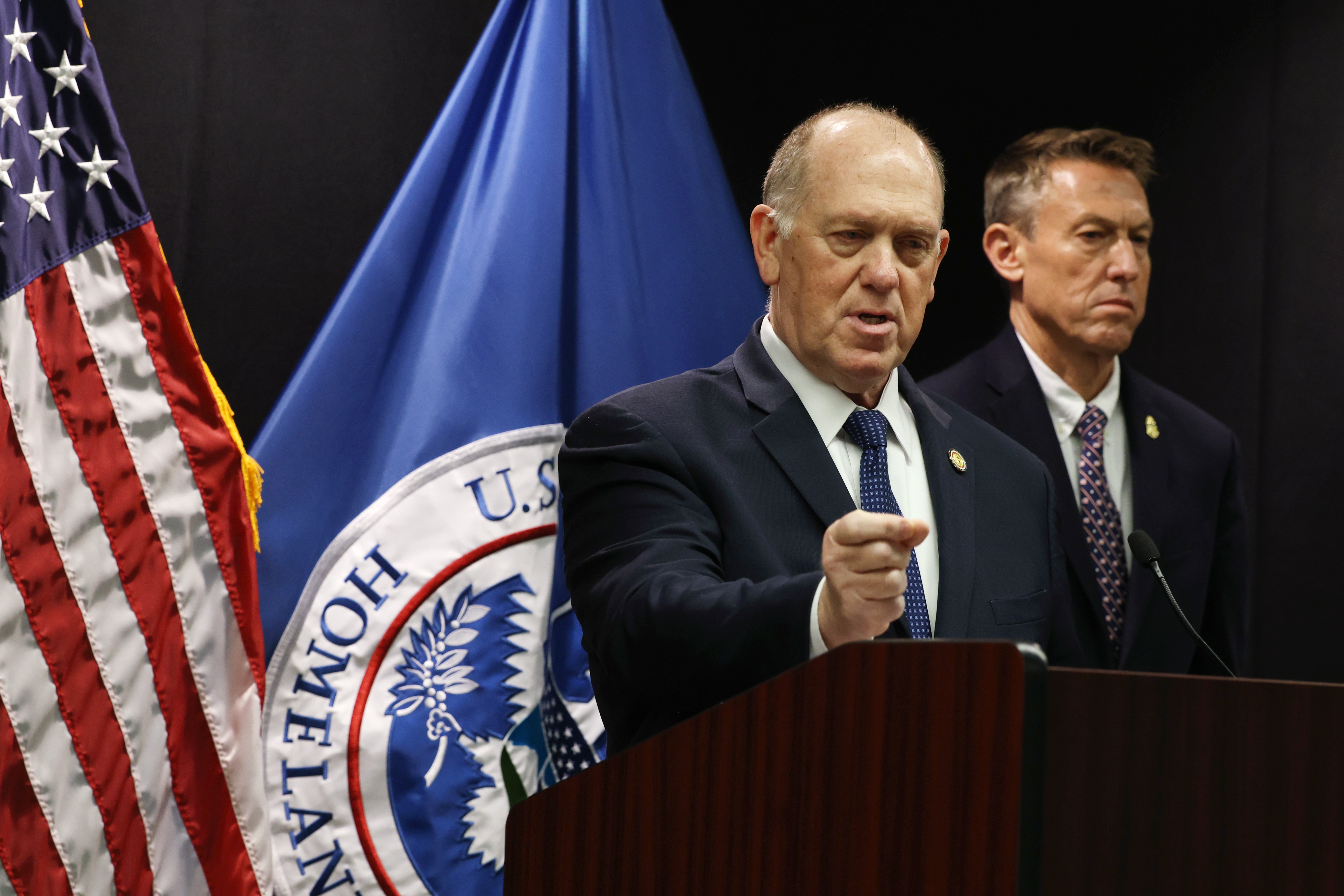

In his place, the president has dispatched his border czar Tom Homan to the city. A Trump ally, Homan has decades of experience in immigration policy across both Republican and Democratic administrations.

On Thursday morning, Homan addressed reporters for the first time, but deliberately skirted around the shootings.

Instead, he insisted the administration would not retreat from the president’s immigration crackdown, adding that Trump could reduce the number of immigration enforcement officers in Minnesota only if state and local officials cooperate.

He did acknowledge missteps.

“I do not want to hear that everything that’s been done here has been perfect. Nothing’s ever perfect,” he said, warning that protesters, including ICE commuters, could face consequences if they interfere with federal officers.

That has done little to deter activists like Stancil.

As he patrols, he is alerted to the presence of ICE agents in an otherwise innocuous compact SUV.

He follows the vehicle, turning the corner. There, a foot patrol of other “commuters” in high-visibility vests, who have received the same intelligence, pick it up and begin alerting the neighborhood to their presence by blowing on whistles.

Random cars driving past begin honking their horns. Several people shout “ICE.”

The locals are particularly concerned because the car is near an elementary school, Stancil explains.

It is around school drop-off time and, as we drive past, a third group of volunteers is stationed outside to protect children.

Stancil says that there have been instances of immigrant families being seized while taking their children to school, leaving many parents too afraid to risk the journey.

Volunteers have stepped in to chaperone children, to deliver groceries to families too terrified to go outside and even to walk their dogs.

“ICE have been here for weeks. They destroyed the city. They are ruining us economically,” says Stancil, who is exhausted. He has been doing this for 21 days straight and has been tear-gassed and pepper-sprayed.

“The cost-benefit here makes no sense as an immigration operation ... It only makes sense as political intimidation.”

The consensus among volunteers and activists The Independent speaks to is that this has little to do with immigration and more to do with punishing Minneapolis.

Many residents believe it is retribution for the 2020 protests that spread across the country during Trump’s first term, following the murder of George Floyd. The 46-year-old Black man was killed by White police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis, who knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes.

Minneapolis is also home to the largest Somali population outside Somalia, something Trump has repeatedly mentioned, Stancil adds.

“I think they have a deep ideological belief that places like Minneapolis have to be brutalized and our non-white neighbors have to be taken away,” he says.

His riding companion, Brandon McCollam, 30, also a volunteer, adds: “Trump himself has called it retribution.”

Back at the mobile home park, Blue Flame is greeted by another volunteer, who she doesn’t know but is answering a similar call. In his own car he says he will watch the neighboring area.

She believes border control is not going anywhere and that they are in it for the long term. She fears a similar mass deployment will happen in other cities. That means the volunteer networks need to maintain momentum.

“We need to think of ICE resistance as a part-time job moving forward,” she says, grimly.

“I have never experienced anything like this in my life. This feels historic. We are living through history.”

Journalist goes live as FBI arrests her over Minnesota church protest

Disabled man dies after his caretaker father was detained by ICE in Dallas

Trump officials met with Canadian separatists that want to break from rest of country

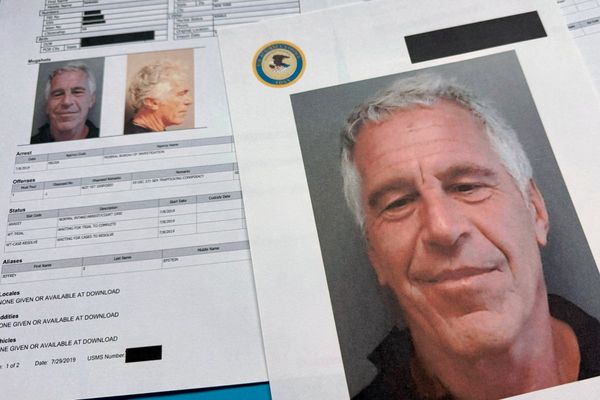

Epstein documents live: DOJ publishes 3 millions of new pages from the case files

Suspect offers to buy police dinner after being taken down in chase

ICE ramping up surveillance with face scans and data tracking