“I wanted to rub the human face in its own vomit, and force it to look in the mirror.” That’s the novelist J.G. Ballard, explaining why he wrote what is arguably the most important novel of the 1970s, the scandalous Crash.

My hunch has always been that – if pressed properly – Bret Easton Ellis might offer an equivalent rationale for his exceedingly controversial satire, American Psycho.

Irresponsible, indefensible, irredeemable. A book so depraved it still has to be sold in shrink-wrapped packaging in Australia.

You name it, Ellis’s most notorious work of fiction probably wallows in it. Abject misogyny, white supremacism, rampant homophobia – that’s in just the first chapter. Yet the fact is that the book matters. Indeed, I believe American Psycho is the most important novel of the 1990s.

Read more: Friday essay: scary tales for scary times

Mergers and murders on Wall Street

“Abandon all hope ye who enter here.” The book’s first words get straight to the heart of it. Mergers and acquisitions, murders and executions. These concerns animate what passes for plot in American Psycho.

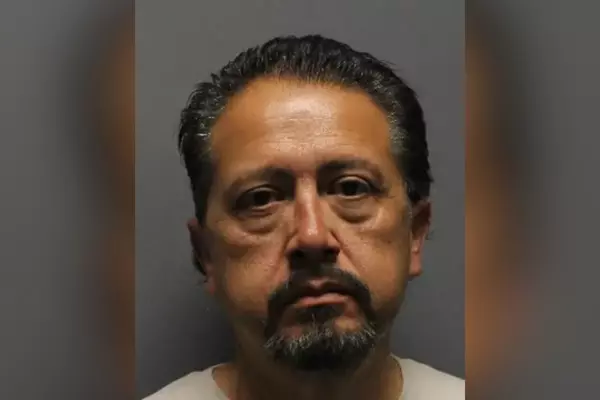

The first-person narrative, which takes place in late-1980s New York City, centres on 27-year-old Harvard graduate and Wall Street finance specialist, Patrick Bateman.

A platinum Amex card, good looks, and a David Onica hung upside-down above the fireplace in his exclusive Upper West Side apartment. This white cis Young Republican – completely obsessed with Donald Trump – enjoys the finer things in life.

We know because he tells us this repeatedly – in excruciatingly detailed, tonally flat prose. The Art of the Deal, Huey Lewis and the News, the original British cast recording of Les Misérables: these are a few of Patrick Bateman’s favourite things.

So, too, are unspeakable acts of torture, sexual assault and homicidal violence. Again, we know because Bateman tells us – in graphic and nauseating detail. It soon becomes apparent that Bateman simply cannot help himself. Nor does he care to.

Read more: Psychopaths versus sociopaths: what is the difference?

Things only get worse

As Bateman himself acknowledges about two-thirds of the way through, his “rages at Harvard were less violent than the ones now and it’s useless to hope that my disgust will vanish – there is just no way.”

In fact, things are only going to get worse:

My conscience, my pity, my hopes disappeared a long time ago (probably at Harvard) if they ever did exist. There are no more barriers to cross. All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, the vicious and the evil, all the mayhem I have caused and my utter indifference toward it, I have now surpassed. I still, though, hold on to one single bleak truth: no one is safe, nothing is redeemed. […] My pain is constant and sharp and I do not hope for a better world for anyone. In fact I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no one to escape.

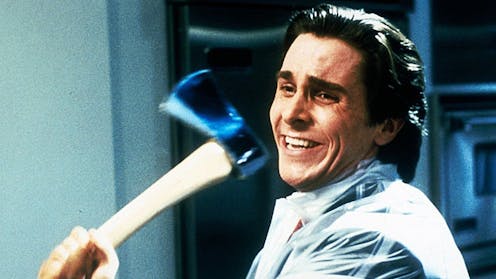

This memorable monologue – portions of which feature in the closing moments of feminist filmmaker Mary Harron’s subsequent adaptation of the novel – is delivered in a chapter near the end of American Psycho.

The title of the chapter in question – “End of the 1980s” – is significant. By this point, Bateman, whose grip on reality was tenuous at best to begin with, has spiralled completely out of control.

He admits to this in the final chapter:

I’m having a sort of hard time paying attention because my automated teller has started speaking to me, sometimes actually leaving weird messages on the screen, in green lettering, like “Cause a Terrible Scene at Sotheby’s” or “Kill the President” or “Feed Me a Stray Cat,” and I was freaked out by the park bench that followed me for six blocks last Monday evening and it too spoke to me. Disintegration – I’m taking it in stride. Yet the only question I can muster up at first and add to the conversation is a worried “I’m not going anywhere if we don’t have a reservation someplace, so do we have a reservation someplace or not?” I notice that we’re all drinking dry beers. Am I the only one who notices this?

Bateman is the only character to notice this. The other yuppies in the bar have other things on their minds. Some are fretting about the amount of fibre in their diets. Others are fixated on figuring out who’s handling the Fisher account.

Read more: Bret Easton Ellis: countercultural bad boy to grumpy Gen-Xer in eight essays

Reagan’s America and looking ‘undangerous’

One – Timothy Price – doesn’t notice because he is transfixed by something else entirely. “I don’t believe it. He looks so … normal. He seems so … out of it. So … undangerous.”

However, Price isn’t describing the homicidal co-worker – whose crimes remain unpunished at the novel’s close – sitting next to him. Rather, he is talking about Ronald Reagan, whose image is being beamed into the bar via a TV screen.

“How can he lie like that? How can he pull that shit?” These are the questions that a strangely incandescent Price puts to the rest of the group, Bateman included.

This is the second and final time Reagan appears on a TV screen in the book. Though Ellis doesn’t specify, it seems probable that Price is reacting to a rerun of the former President’s infamous national address about his involvement in the Iran-Contra scandal.

Reagan, referred to by name on three fleeting occasions in this sprawling, near 400-page novel, is the key to understanding American Psycho, and why it matters.

I mentioned before that Ellis’s grotesquely violent novel is irreducibly misogynist, racist and homophobic. It is all these things precisely because Reagan’s America was exactly that.

The America of the 1980s was, lest anyone forget, the America of Reagan’s coded racist statements and social policies. Like the myth of the “welfare queen”, a derogatory term designed to erode public sympathy for impoverished women of colour. The way the political right continued to draw inspiration from the so-called “Southern strategy” (an underhand and noxious electoral strategy first developed in the Nixon-era that sought to appeal to bigoted voters). And White House press conferences that offhandedly and laughingly dismissed the unfurling HIV/AIDS epidemic as a “gay plague”.

In this sense, then, American Psycho is less darkly comic satire than deadly serious and invaluable social diagnostic. As with Ballard’s Crash, Ellis’s novel – obsessed as it is with surfaces, appearances and reflections – holds up a mirror up to the reader, daring them (us) to look squarely at the horrific lived reality of late capitalist America.

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.